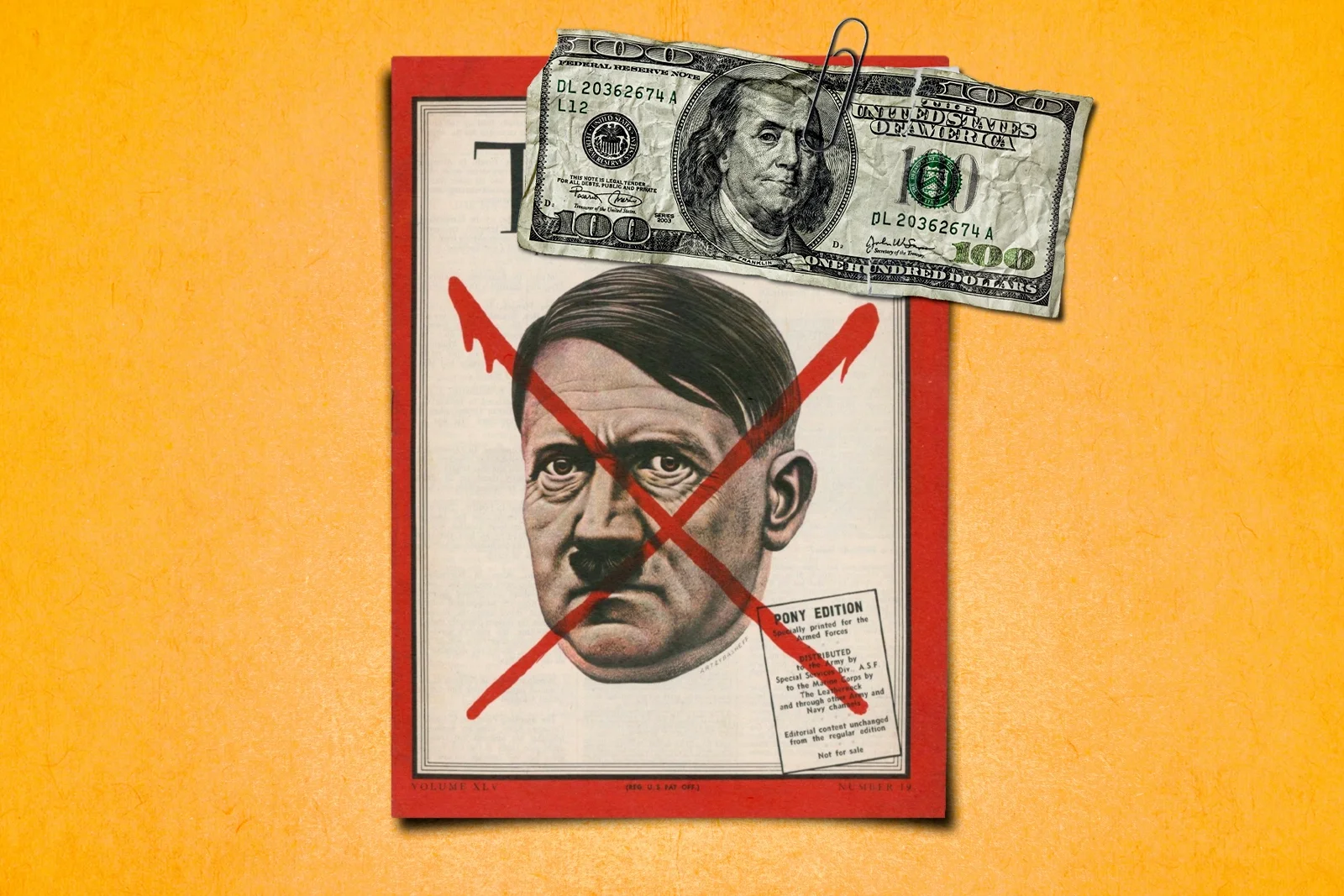

Filmmaker Jason Weixelbaum on American Corporations, Nazi Germany, and the Fight for Memory

Jason Weixelbaum is a historian and filmmaker whose work explores the moral entanglements of American corporations with authoritarian regimes, especially Nazi Germany.

After witnessing ethical lapses in the mortgage industry during the 2000s, he pursued a Ph.D. examining U.S. companies like Ford, IBM, and GM under Nazism. He founded Elusive Films in 2020 and created A Nazi on Wall Street, a dramatized series about a Jewish FBI agent targeting Nazi influence in 1940s New York.

Weixelbaum emphasizes how historical patterns of authoritarianism echo today through populist politics, corporate complicity, and the erosion of ethical accountability under capitalism in crisis.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Thank you for joining me today and contributing to this broader project—a forthcoming book compiling conversations with diverse experts on antisemitism.

Jason Weixelbaum: I appreciate it. I’m glad someone is listening. Sometimes, I feel like I’ve been shouting into the void for years.

Jacobsen: Over the years, I’ve learned that one of our family members was recognized for sheltering a Jewish couple during the Second World War. I have some Dutch heritage, which explains my blond hair and Northern European features.

What initially drew you to the intersection of American corporate history and Nazi Germany?

Weixelbaum: That’s a good story. Once upon a time, I dropped out of art school. To support my painting and rock music lifestyle, I played in bands in my early twenties, and I took a job where they were hiring: the mortgage business.

In the early 2000s, refinancing was booming, and I ended up in mortgage-backed securities. I had no idea at the time that I was part of a rapidly growing economic bubble that would eventually collapse in 2008.

Eventually, I worked in a bank’s mortgage securities department. I was not a trader and certainly was not making large sums of money. I earned ten dollars an hour to help process large securities transactions—the kind that later became infamous in films like The Big Short.

On my first day at this particular financial institution—located in a large, mostly empty mall converted into office cubicles—I was instructed to process a $200 million “pool” of mortgages. In industry terms, a “pool” is a bundle of home loans sold as a mortgage-backed security. My job was to stamp mortgage notes sold to another institution—which no longer exists because it collapsed during the 2008 financial crisis—and to enter borrower data into a system.

I meticulously checked them all, then hit “send,” and a big red error box popped up on the screen. It was my first day, and I was trying not to freak out. I went back and double-checked every single Social Security number, dollar amount, income, loan amount—everything. Then I hit “send” again.

There is a big red error screen.

Now, my boss sees the distressed look on my face. She approaches my cubicle, sits at my terminal, and asks, “What’s wrong?”

“I—I don’t know. It won’t send.”

So, she’s looking through the different pieces of data. I notice she’s starting to change numbers—changing incomes here and there. Then she says, “Try it now.”

She gets up. I sit back down at my terminal and hit “Send.”

A big green bar comes up: Sent successfully.

And then—nonchalantly—she says, “Next time, do that with all of them,” and walks away.

I spent three more years in that department, trading approximately $2.5 billion of mortgage securities. Of course, I was part of a larger department, but I had that level of responsibility.

I was in my early twenties. This was my intellectual awakening. I thought, “If I’m going to be in this place, I might as well learn about finance, banking, and mortgages.” What’s going on here?

And that’s when it started to dawn on me that this was going to be a huge problem for the world. This was going to cause an economic catastrophe. My morale sank more and more the longer I stayed.

One day—this was still two or three years before the crash—I was sitting at a bus stop after work, feeling particularly low about what I had done all day. They weren’t even paying me enough to afford a car. It was poetic, in a way—while I was helping to crash the world economy.

Right next to the bus stop, there was a bookstore. In the window, I saw a book about a company operating in Nazi Germany. Side note: Around the early 2000s, several books were published on the topic, partly because several large-scale Holocaust restitution lawsuits had recently concluded—some of which involved major companies. That brought renewed attention to corporate complicity in the Holocaust.

So I walked in, saw that book, and felt an immediate connection. These businesses might have had good reputations on the surface but were doing things with tremendously grave outcomes.

It took a little while, but I can pinpoint that moment when I decided to quit that job, return to school, and begin again—starting my undergraduate degree as a historian, studying this topic. I was pretty single-minded. I wanted to know more—what this was all about. I fell down the rabbit hole. An undergraduate degree turned into a master’s and a doctorate.

Jacobsen: Looking back at your time in the mortgage securities industry during the early 2000s and the decision to investigate corporate ethics during the 1930s—is there some truth to that Mark Twain quote “history doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes”?

Weixelbaum: Oh, I’m glad you brought that up. As the founder and executive producer of Elusive Films, we have a tagline: “Every time history repeats, the price goes up.”

Yeah, that’s pretty accurate.

It does rhyme. I am seeing some very similar behaviour today in the American business community and their reaction to—what I call—the regime. It is enough to say that. The range of different approaches these businessmen take is fascinating.

When I started studying this, my surface-level understanding was very populist—torches and pitchforks. “Let’s get the bad corporate guys—they’re all evil,” that sort of thing. But if you’re doing history right, you begin to develop a respect for subtleties and nuance. Different business people have different motivations and approaches.

Some were true believers in the fascist cause—Henry Ford, for example. Others were far more amoral—Alfred Sloan of General Motors comes to mind. They just wanted to win the corporate race. Then, others knew they were doing something wrong but tried to cover it publicly as if they were doing the right thing.

I am thinking about Thomas Watson of IBM. He very publicly returned his Nazi medal and wrote an op-ed in The New York Times denouncing Nazism. But at the same time—simultaneously—he was fighting tooth and nail to retain control over IBM’s German subsidiaries. So there’s a range of approaches.

While we do not need to get into the weeds here, the field of corporate social responsibility also outlines different models for how business leaders respond. Some want to actively erase or forget their ties to authoritarian regimes, while others are content with apathy. It depends on the context.

Jacobsen: Elusive Films is relatively new. It was founded in 2020, marking your transition from academia to filmmaking. With A Nazi on Wall Street, which is based on the true story of a Nazi spy operating in 1940s New York and the Jewish FBI agent determined to stop him—how did you uncover this narrative? This sounds like Mark Wahlberg going after Brad Pitt.

Weixelbaum: [Laughing] Oh gosh—yes, get this script to them!

We’ve spent the last several years developing an incredible pitch. It’s a project that’s being taken seriously by people in the entertainment industry. But as with everything, it is all about who you know. We’re told we have a great pitch—but we need to get it in front of some big movers and shakers. That’s one of the main reasons I’m talking to you—trying to get the word out.

This company—and this project—was born out of grief, Scott.

I was trying to find my way with a Ph.D. in history and business ethics. As you might imagine, that is not the most profitable path. I was doing some compliance work. Then, in December 2019, my father—who had spent his entire life in the entertainment industry, a TV actor in soap operas and films, a wonderful, wonderful man, the center of my world—got a mysterious respiratory virus.

Nobody knew what COVID-19 was yet. Maybe if you were paying close attention to the news here in the States, you would have an idea. But it took him very quickly. I was standing in the doorway of my row house in Baltimore after leaving work early on New Year’s Eve when I got the call from the ICU. As the eldest child, I had to decide to let him go—to turn off the respirator.

And, to put it mildly, I was destroyed. Destroyed. Then, only a month later, I was laid off. And a month after that, the entire world shut down. So there I was—devastated, unemployed, sitting on my couch with a completed Ph.D.—thinking, “What the hell am I going to do?”

And I wanted to find some way to honour my father’s legacy in television. He had been an actor for fifty years.

He also produced and directed for the stage and on screen. So I brought together a group of my creative friends—producers, writers, composers, designers—and asked them, “What if we tried to do this? What if we tried to make a TV show?” This is to answer your question, though I know it is a roundabout way of getting there.

I came across this incredible story of a Jewish FBI agent chasing a Nazi spy around New York City. It was not quite dissertation material, so I could not use much of it in my doctoral work. But it captured my imagination for a long time. Even the Nazi spy himself—who was connected to many of the companies I studied—kept popping up. I did not get to write much about him individually because I was focused on corporate case studies.

Still, this story had been kicking around in my head for quite some time. And as a vehicle to bring people into a first-person view of history, I don’t want to do a documentary. Everyone assumes, “Oh, I can’t wait to see your documentary.” But

I’m not doing a documentary.

I want to do a dramatization—on purpose—because it can reach the broadest possible audience and allow them to connect to the story through a human lens.

This FBI agent—whose story I can get into more deeply—was essentially trying, almost single-handedly, to stop the infiltration of Nazism into American business.

Jacobsen: What is the mindset of someone who is fully indoctrinated—functioning as a political vanguard for an ideology like Nazism? Someone virulent enough that even in another country, in a cosmopolitan city, they still carry and act on this ideological construct of mind.

Weixelbaum: This is where history meets the present.

Many others, people much more accomplished than I am, have written on this topic. But I do have a specific take: populism—grievance politics.

Now, I know there’s an ongoing debate about what populism is, but this is my definition. And because I have a doctorate, I get to make up my definitions of political terms—so you’ll have to bear with me. Populism—the pop politics of grievance—is always present. It’s like background radiation. It’s anthrax in the soil.

Populism is always present, especially in liberal societies where surface-level stability exists. It flourishes in those environments precisely because it does not live in a world of facts. It lives in a world of emotion—of outrage.

It jumps from one target to another. Rhetoric is irrelevant and can be shifted at will. The cause is irrelevant—it can be swapped out. Many people have trouble distinguishing left-wing and right-wing populism from actual liberalism or progressivism. The populist rhetoric is always the same: the people versus the elite. And the “elite” is changeable. It could be bankers. It could be academics. It could be the wealthy. It could be media figures. You name it.

Unfortunately, over a long enough timeline, in societies where populism thrives, Jewish people are often cast as the elite—those who must be stopped or destroyed. Populists always need new enemies. That is the actual mechanism. Any cause becomes a vehicle for continuing that pattern of scapegoating and persecution.

In my view, across the arc of history, populism has become very attractive when people feel particularly anxious or afraid, especially in times of great social or economic transformation.

Populism was prevalent in the 1920s and 1930s, and it is still prevalent today. It gives people a simple explanation for their fear: “I feel anxious, so I’ll go find the bad guys.”

The big bad guy is over there. I can dominate them, feel a little better about myself, and distract myself from my own fear and anxiety. The problem is that this kind of movement—this populist impulse—is extremely powerful for demagogues. And it is not limited to the disenfranchised. It is attractive to people who already hold wealth and power. They, too, are afraid. The more you have, the more afraid you may be of losing it.

Sorry—again, it’s a bit of a roundabout way to answer your question. However, populist movements were happening all over the place in the 1930s. Henry Ford is a great example. See if this sounds familiar: We have a wealthy person who did well in an industry but did not appear well-educated. He lacks critical thinking instincts and is surrounded by conspiracy theorists. They get their hands on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—an antisemitic hoax text originating in Russia.

And it changes his worldview. He becomes convinced there is a global Jewish conspiracy aiming to control the world.

And unfortunately, because Ford had so much money and influence, he could put these conspiracy theories into action. He began publishing the Protocols in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent. He learned of Adolf Hitler and began sending money to the Nazi Party—although that topic is still under scrutiny by historians. He had The International Jew, his antisemitic publication, translated and distributed widely. So, no—wealth does not insulate you from ignorance. Critical thinking does not come with a big bank account.

That is where we see the toxic mix: populist sentiment, conspiracy theory, and immense wealth and influence. This was very much alive among segments of the American business community in the interwar period. And we could talk about other figures—businessmen who believed the world should be carved into spheres of influence. It sounds familiar again. These are not good dynamics.

Of course, eventually, the pattern emerges clearly: populists always destroy what they claim to protect. It is only a matter of time. Populism ultimately consumes itself. It does not build. It only tears down.

Jacobsen: Your father was an actor in film and television for fifty years. Did he—or his legacy—help influence your career path?

Weixelbaum: Yes—this is a passion project. It started because I needed something to do with my grief. I wanted to honour his legacy in some way. I do not think his work in soap operas and beach movies directly inspired the content I am working on now. But as a person—absolutely—he influenced me profoundly.

It was a great honour to have a father who would call me and say, especially after he retired, “I’ve been reading the news. Tell me, historian son, what the hell is going on?” He would call me regularly. He was engaged. He was curious. And that intellectual curiosity, that desire to understand the world—was a big part of who he was and what I carry forward.

We used to have these great, detailed conversations about why Reconstruction failed and how that failure continues to shape American politics today. I’d also talk to him about populist movements or similar topics. For me, continuing this work is a way of still having those conversations with him.

Jacobsen: Right-wing, far-right ideologies and political violence in the United States have been on the rise. The most active domestic terrorist groups in recent years have been white nationalists—often associated with Christian religious identity and tied to ethnic supremacist views. Statistically speaking, one could argue that the largest ethnic group and the dominant religion—white and Christian—are the most likely sources of this kind of terrorism. So, if you were to throw a dart randomly at a Venn diagram of potential culprits for right-wing terrorism, you’d likely land in that intersection. But of course, there are more nuanced takes to consider. What are some of those more nuanced perspectives?

Weixelbaum: I typically seek out the work of other experts in this field. There are many outstanding scholars—both living and deceased—whose research has deeply influenced my thinking. I would not claim to be more of an expert than they are, but I can speak to the patterns I see.

As I said earlier, this links directly to the anxiety people feel about their place in society—and how that fuels populist movements. We’re talking about right-wing populism here, and its most extreme version is fascism. Unsurprisingly, people join these movements when they feel their social status is threatened. Many white Christian nationalists in the U.S. have long believed themselves to be the default holders of power. But in a multiethnic democracy—especially one moving toward a “majority-minority” population—they see that dominance slipping. That anxiety becomes fuel.

There’s a direct connection between that fear and the rise of extremist movements. And I’m just one of many scholars who have made that observation. These conversations float through a lot of morally gray territory and deserve careful, continuous engagement.

Jacobsen: In your contribution to public discourse, how do you view the intersection of corporate ethics, historical accountability, and the prevention of authoritarianism? To what extent are ethical demands on corporations reasonable—and when might they become unfeasible?

Weixelbaum: Great question. It touches the core of my professional work throughout this project. I also work in ethics in a professional capacity. What’s hard to watch today is that we’re seeing the same patterns repeat.

You have businessmen who tell themselves comforting stories: “It will be fine. He’s our dictator. He’s a businessman. He’ll help us.” But it is all nonsense. As things progress, it rarely ends well when businesspeople engage with authoritarian movements. Populism is not rational. It’s not predictable. That is not a good environment for a long-term business strategy.

So yes, corporate ethics are vital. One of the biggest myths in my field is that American companies made massive profits in Nazi Germany. People often ask me, “How much money did they make?” The answer? Most of them lost money. Think about it: you’re an American executive and return to your factory in Germany in 1945. The factory is rubble. Your bank account is full of valueless Reichsmark from a defeated regime. And if the public finds out what you did, your company’s reputation is in shambles. There’s no profit in that.

Sure, you can argue that some companies gained market share after the war by eliminating competition, and some were well-positioned for the postwar boom. That is true in some cases. But we are seeing echoes of the same delusions today. Corporate leaders say things like, “The tariffs will be fine, or this will pass,” and it is clearly not fine.

At the time of this interview, the market reaction has been terrible—this is not a moment of validation for those who supported authoritarian figures and their enablers. So yes, corporate ethics matters. And some companies are trying—they value transparency, emphasize people over profits, or at least try to go beyond lip service.

However, where the scholarship in corporate ethics intersects with history is in practice. Today, companies can choose to be certified as ethical or transparent. Some have learned from history. But many—frankly, most—have not—not even close.

Jacobsen: Would you say that what we’re witnessing today is a resurgence of fascism in the truest sense? Or is it more appropriate to view fascism as a phenomenon bound to a specific historical moment, making today’s developments better characterized as a broader rise in authoritarianism rather than fascism itself?

Wexelbaum: [Laughing] If it doesn’t come out of Germany, it’s merely sparkling authoritarianism, right? I mean—sorry to keep pointing to this vague body of scholarship—but there is so much debate over what exactly constitutes fascism.

I’m looking at a section of my library next to my desk—bookshelves full of works, each offering a slightly different definition: “My exact definition is fascism.” It gets academic fast. That said, I generally think that, yes—right-wing authoritarianism took to its logical conclusion. We can call that fascism. We can use the F word and not feel too weird about it.

One of the really important projects in political discourse today is to be intentional about the words we use. I think—maybe this is partly the influence of social media—but people throw around terms like liberalism, leftism, populism, fascism, and progressivism constantly and rarely stop to reflect on what they mean. I do not see much discussion that’s useful or grounded.

And it’s okay to debate those terms. Scholars do it all the time. We should not take them for granted. So, yes, my broad understanding is that right-wing populism, taken to its extreme, leads to fascism. That means a demagogue becomes a dictator, and the movement itself runs on emotional cycles—finding new enemies to destroy repeatedly.

Where it gets more contentious—and especially relevant to our conversation—is in the relationship between capitalism and fascism, between business and fascist regimes.

As you might imagine, many people want to use the kind of historical work I do to support their political positions. I am not always thrilled about that. Some want to use the story of American companies operating in Nazi Germany as evidence that America has always been morally bankrupt. Well—maybe. But that’s not the whole story.

There were plenty of Americans, like the main character in A Nazi on Wall Street, who were actively trying to stop those alliances who were fighting fascism.

On the other hand, some want to argue that the Nazis were just puppets of industrialists—that capitalists were secretly pulling the strings behind Hitler. That is also not quite right. Hitler and the Nazi movement were already robust and ideologically driven before they came to power.

And once they did take over the German state, business leaders—especially German ones—had limited choices. It was not a matter of cozy alignment. It was compliance under threat. Once the Nazis consolidated power, business people were expected to cooperate—or face the consequences. If you disobeyed, someone would come to your house.

So, even in those contexts, there is still a range of behaviors. Some people were true believers, and it was profitable for them. Others did what they had to do because, frankly, they did not have a choice.

What’s so interesting about Americans who did business with the Nazis is that they were never under threat from the Gestapo. If they had chosen to walk away, no one would have shown up at their home in the U.S. There was a lot more room for negotiation, for exerting agency. And that power dynamic—between American business leaders and the Nazi regime—is something I find endlessly fascinating.

Readers might find this particularly interesting if you do not mind indulging me for a quick example. General Motors, at a certain point, wanted to make it appear as though they were not profoundly entangled with the Nazis. At the same time, the Nazi state was uneasy about relying so heavily on an American company—one that was, by far, the largest automaker in Germany at the time. People often talk about boycotting Volkswagen, but if you wanted to disrupt Nazi military production, you would have targeted General Motors. The scholarship on this is deep, and I could go on for hours.

Anyway, the Nazi regime and GM both knew the situation was delicate. So General Motors said, “We’ll stay, but we want our guy—our hand-picked Nazi—to run our German subsidiary.” After some negotiation and trial and error, they found a man who fit the bill. There was a revolving door of executives until they landed on someone who could maintain that balance. It was all very calculated.

That is just one example of how nuanced the relationship between capital and fascism could be. It was not just blind support or total victimization—it was messy, strategic, and often self-serving. And, of course, as the war progressed and things deteriorated, the American companies lost money. Their factories were bombed. Their assets were frozen. Their reputations suffered.

And gosh—does that sound familiar? It’s the same pattern: People think they will benefit in the short term from backing authoritarian actors, but in the long term, it almost always goes badly.

Jacobsen: How much are current American events paralleling the 1930s and 1940s historical occurrences? In other words, how much are people reading the situation correctly, and how much are they buying into left, centrist, or right-wing hyperbole?

Wexelbaum: Yes, what’s endlessly fascinating—and also maddening—about the history of Nazi Germany is that it has become a kind of Rorschach test. People project their anxieties and politics onto it. And if you invoke it too often or carelessly, it can be stripped of all real meaning.

The America of 2025 is not Nazi Germany for many reasons. First, it’s simply a much bigger country. Creating a totalitarian state in Germany in the 1930s was a very different enterprise from trying to do so in a nation of 350 million people.

That structural difference is, I hope, a saving grace for Americans who are worried about the direction of their country.

Also, today’s authoritarian-leaning movements in the U.S. are far less organized than the Nazis were. The Nazis had paramilitary wings, a centralized ideology, and a deeply developed propaganda system well before taking power. What we see now in the U.S. is much more chaotic—more fragmented.

That said, the rhetoric, the targeting of vulnerable groups, and the populist grievances rhyme with history, and we must pay attention.

This is an important story, and we can close with this.

For a few months during a long stretch of dissertation research, I became obsessed with reading the documents from the American Embassy in Nazi Germany, particularly in 1938. Specifically, I focused on the records from the Commercial Attaché’s Office. This office, housed within the U.S. Embassy in Berlin, studied economic trends and monitored the attitudes of American businesses operating in Germany and German businesspeople.

I highlight 1938 because it was a moment of intense global fear. Those who study this period know that the world had just experienced the Great Depression—a traumatic economic collapse that affected every industrialized nation. Both the United States and Germany had begun to recover in different ways. They found strategies to stimulate their economies; by the mid-to-late 1930s, some growth had returned.

But in 1938, another recession loomed—the first major signal of economic trouble since the recovery began. And that scared the Nazis to death. In those embassy records, I was surprised by just how much anxiety I saw—especially from people running a totalitarian state. These were not democratic leaders who feared losing an election. The Nazis had outlawed all other political parties by that point. But still, in 1937 and 1938, they were worried.

Why? Because even in a one-party dictatorship, you have to manage public perception. Even among supporters of the regime and the politically disengaged, public morale matters. Populist and authoritarian regimes require a foundation of stability to function. When the economy falters, the emotional rhetoric of grievance becomes hollow. You cannot feed people with propaganda. If they are well-fed, you can sell them all the grievance you want—but when hunger sets in, outrage loses its power.

Stability is the oxygen for authoritarian and populist regimes. But here’s the paradox: those regimes almost always destroy the very platform they stand on.

And the Nazis did exactly that. They eventually obliterated their foundation by launching a global war. So, bringing this back to the United States is a real and pressing concern. Authoritarianism cannot thrive without economic and social stability. I think the Nazi regime, for all its evil, understood that far better than the current American regime does.

You cannot build a durable authoritarian state on chaos. Even the Nazis—who were far more disciplined and ideologically cohesive—envisioned a “Thousand-Year Reich” and only made it twelve years. Not exactly a strong track record.

What will be the track record of this current regime in America? Well… time will tell.

Jacobsen: Jay, thank you for your time today.

Wexelbaum: Sounds great. It’s good to meet you, Scott.