Foreign Investment: Why Does the U.S. Mistrust China?

Perhaps the West never really understood 韬光养晦, the Chinese expression tao guang yang hui, that conveys a sense of remaining hidden, or keeping a low profile, while advancing one’s strategic goals.

When Deng Xiaoping used the expression to describe China’s foreign policy, it was often interpreted – despite its nuances – to mean that Chinese growth and global influence adheres to the philosophical guideline of modest, measured and methodical development, as if it were an indelible character trait.

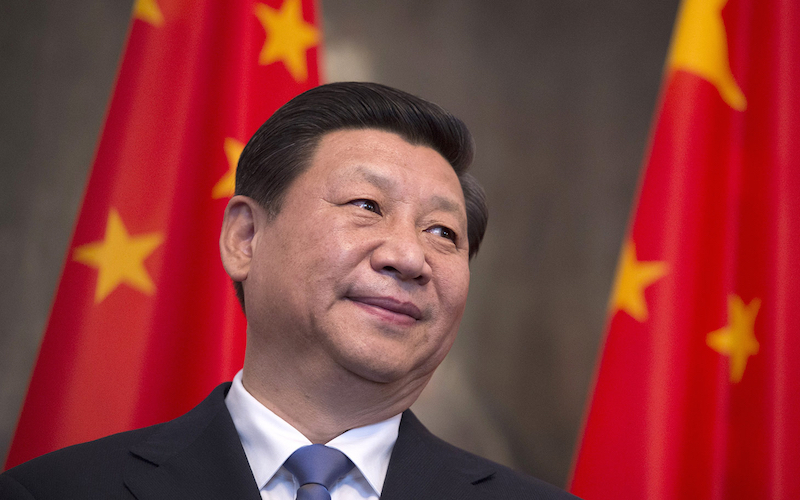

Yet it can also mean “biding one’s time” in a stealthy and opportunistic way. As recently as seven years ago, Hu Jintao invoked the principle in describing China’s commitment to peaceful development and international diplomacy. In a more imposing China under Xi Jinping, the nation’s aggression on multiple fronts – in the South China Sea, in its African influence – may at times be covert, but it is no longer coy.

Similarly, China’s bold foreign investment moves suggest that its party’s officials, economists and business leaders think the Middle Kingdom’s time has finally come, as evidenced by the most recent $43 billion bid by ChemChina to acquire Syngenta.

The deal reflects an expansive trend in foreign investment, with China’s outbound M&A at $68 billion so far this year, as China seeks to offset its lagging economy and secure critical resources. These include the access to biotech and agricultural innovation that the Swiss-owned Syngenta represents in food security terms.

But there will be no deal without United States approval, because Syngenta facilities along the Gulf Coast are subject to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s antiterrorism requirements for hazardous chemical facilities, and therefore require approval of any foreign investment from a different low-profile entity: the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). The CFIUS has already shot down three Chinese deals in 2016, in a regulatory framework that may prove to be one arena in which the U.S. suspicions of China have long been cultivated – on trade, cyberespionage, intellectual property.

Sour Sino-U.S. deals are getting expensive

On January 22, a $3.3 billion deal delivering a majority interest in Philips Lumileds to Chinese investors, led by GO Scale Capital, was pulled following the CFIUS ruling; the multiagency committee, appointed by the U.S. president, is not required to report its reasons. That lack of transparency has drawn attention to its authority before, notably in 2013 when the $4.7 billion sale of Smithfield Foods to China’s Shuanghui International Holdings Ltd. – then the largest acquisition of a U.S. firm – was challenged on food security grounds, with opposition from American farm interests, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, and others who raised questions about intellectual property rights rooted in Smithfield’s biotech advances.

In the U.S., there are already advocates in agricultural sectors drawing parallels with the Syngenta case, and some analysts argue that China’s move is about feeding 1.4 billion people, not its economic power. The emphasis on seed, pesticide and biotech patents is making for strange opposition bedfellows of agribusiness and environmentalists.

The Philips deal, however, involved advanced semiconductor technology used at the Dutch company’s plant in California. The CFIUS denial of that acquisition was followed by the February 16 announcement that Fairchild Semiconductor had chosen to refuse a takeover bid from a Chinese company, citing CFIUS authority as an unacceptable level of risk. The next week, Chinese investors pulled out of a third deal with Western Digital on the news that CFIUS planned a review. Unisplendour, the Chinese buyers, exercised a specific CFIUS-related contractual provision, one of the strategies Chinese firms are using to navigate U.S. barriers and fears.

No compromise, no deal on cybersecurity

China’s aggression remains very much a concern for the U.S. and other nations, regardless of how the Chinese try to sweeten those business deals. Some analysts say the only direct correlation between “aggressive” Chinese strategies on trade, and any alarming military or other strategic changes under Xi, is a shift in the U.S. diplomatic response; China’s peaceful development is now amplified, not different.

That assessment is hard to square, though, with foreign leaders exasperated by China’s state-controlled business practices, currency manipulations, and hacking and intellectual property theft that have made Americans, especially, far more shrewd about the way China has been “biding its time.”

The West fully appreciates China’s strategic investment in innovation, and its transformative power for the Chinese people, but the position of Western – and many ASEAN nations dealing with China – isn’t based in a protective isolationism, so much as it is on expectations of a level playing field.

The failure to hem China in on its business practices has consequences beyond the Hang Seng or Wall Street. In the United States, unfair trade is a recurring theme at Donald Trump rallies – where China’s reputation has political resonance among angry, economically disenfranchised voters headed to the polls in November. In fact, improving U.S. public opinion is one goal of the 2015 bilateral agreement to end cyberespionage.

But Chinese cooperation is still lagging, as the CFIUS and other entities struggle to advance economic and diplomatic goals within a mutual culture of mistrust. It is time – time to insist that Xi and China fix it.