Politics

Gerrymandering is Solvable. But Not the Way You Think.

According to the latest projections from Decision Desk HQ, if the US House of Representatives elections were held today, Democrats would get 54% of the vote. A resounding rejection of Trump, right? Not so fast. They’d get just 47% of the seats.

In the world of politics, a 7% unfair advantage is truly a cavernous gap between the popular will and the election outcome. The simple word for why that can exist is “gerrymandering.” This is when representatives choose their voters, instead of the other way around. By carefully drawing the lines, politicians can devalue certain voters: either “packing” them into one district where they waste far more votes than necessary electing just one representative, or “cracking” them into many districts where their votes are always just short of 50%.

So, if gerrymandering is when they draw crazy-shaped districts, then we just have to make sure districts aren’t crazy-shaped, and that will solve the problem, right? Wrong!

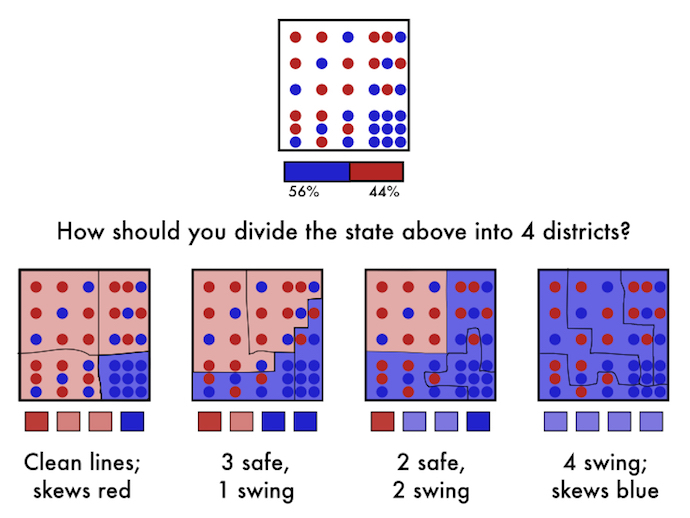

The image above shows 4 ways to divide up a New Square State, which has 56% blue voters, most of whom live in New Square City at the southeast corner of the state. The districts in the leftmost option are the most compact, but they are also the most unfair in favor of the red party. Option 2 is the closest to proportionality, but most districts are not competitive, so corrupt incumbents could remain for years. Option 3 presents a decent balance between proportional and competitive, but some districts are beginning to have a pretty gerrymandered shape to them. In Option 4, the districts are the most competitive, but they are also the least compact and the most unfair in favor of the blue party.

(If you want to play with your own districting plans for New Square State, you can use this web game from @EnDimensions.)

Though this is of course a simplified example, the basic idea is realistic. In a world where the densest urban areas skew far to one side, and most other areas skew slightly to the other, “compact,” “competitive,” and “proportional” are three conflicting goals. You could make good-faith arguments that any one of the districting plans above is the fairest. And if they started with option 4 and switched to a colorblind nonpartisan redistricting commission, they’d probably end up with option 1 — almost as disproportional and unfair.

So that means that when I said above that the 7% expected Republican skew could be attributed to “gerrymandering,” I didn’t just mean “crazy-looking shapes.” I meant to include natural demographic clustering, too. That’s why nonpartisan redistricting, while it would help some, wouldn’t solve the whole problem.

The real problem isn’t just the shape of the districts. It’s the districts themselves. In the picture above, I’ve distinguished safe districts from swing districts, depending on whether the margin of victory is greater or less than 15%. Both kinds of districts have serious problems. In safe districts, politicians pander to the primary election voters, usually skewed towards the most extreme and ideological side of the dominant party. In swing districts, close to 50% of the voters have a representative they voted against, who probably will tend to ignore their petitions.

At its heart, gerrymandering is the intentional engineering of wasted votes. This idea of wasted votes is central to Gill v. Whitford, the anti-gerrymandering case from Wisconsin that’s before the Supreme Court. According to the definition the plaintiffs there use, all the votes for losing candidates, and the portion of all the votes for winning candidates above the total that would have been needed to win, are wasted. They go on to show that the Wisconsin districting plan is clearly designed to maximize wasted Democratic votes. But even aside from partisan concerns, the truth is that with our current voting methods, it’s essentially guaranteed that over 50% of votes will be wasted. Without changing those methods, the fairest result we could possibly hope for is not so much to reduce that vote wastage, but merely to ensure it’s spread evenly between the two major parties.

Gerrymandering is an existential threat to the USA. And a 7% skew is massively undemocratic, but in itself it’s not quite an existential threat. So what do I mean?

Well, just think of the cascade of bad effects that come from the problems above. Safe-district incumbents run to the ideological extremes, leading to a gridlocked Congress unable to deliver realistic solutions to real problems. Parties realize that the more voters they can disenfranchise or discourage from voting, the easier gerrymandering becomes; so zero-sum thinking leads to negative-sum mudslinging campaigns. And if this goes on for too long, the murmurs of secession from the majority voters with minority power (like California) will grow more and more serious.

The obvious solutions won’t work well

I’m certainly not the only one sounding the alarm on this. Books like Ratf**ked by @davedaley3; papers by @katherinegehl and @MichaelEPorter’s account of the anticompetitive “politics industry” (which I reviewed); columns like @Michelleinbklyn’s (that is, Michelle Goldberg, the new NYT opinion columnist) recent “Tyranny of the Minority”; entire conferences like those run by the MGGG at Tufts; all of them are treating this with the urgency it deserves. People like @mlatner, @rickhasen, @rob_richie, and others have been on this issue for years.

But while all of the people I named recognize the problem, their suggested solutions are either weak or unlikely to pass.

The first solution most people think of to the gerrymandering problem is nonpartisan redistricting: take the line-drawing out of the hands of the politicians who benefit from it. And sure, this would certainly help somewhat. But as the example above shows, it wouldn’t solve the whole problem; no matter where you draw the lines, over 50% of the votes will still be wasted, and there will probably still be some partisan skew. In cases where it’s the only possibility, it’s certainly worth doing; but as you’ll see below, we can do better, at least on a national basis.

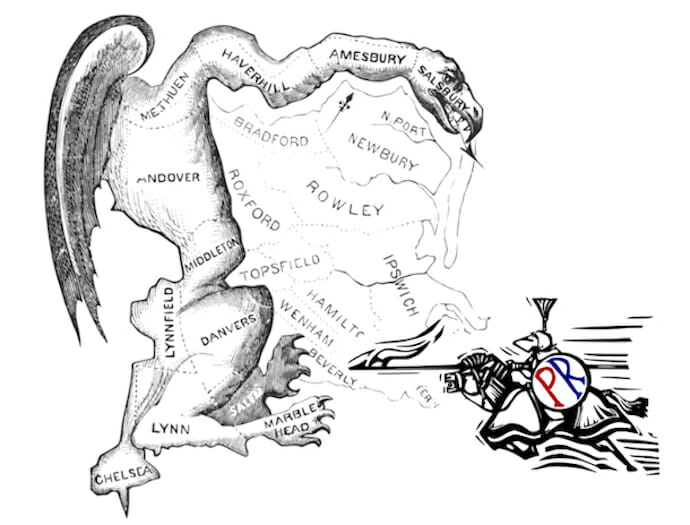

If current voting methods ensure wasted votes, can’t we fix that by changing our voting methods? Indeed we can. The term for voting methods designed to minimize wasted votes is Proportional Representation (PR). By ensuring that each group of voters gets represented in proportion to their size, PR methods can reduce wasted votes to merely the rounding error in the number of seats; a small fraction of the electorate as a whole. For instance, in a state with 9 seats in the House, the maximum wasted votes under a fully proportional method would be 10%, that is, 1/(9+1) of the voters. The technical term for this amount is a Droop quota; I’ll mention this again later.

Several of the thinkers I tagged above have advocated for PR methods in the US. But to actually pass and be implemented, a new PR method doesn’t just need to solve the problem of wasted votes. It needs to avoid creating new problems, especially for those groups who are key to getting it passed. On this ground, most existing proposals leave something to be desired.

Those proposals are mostly based on some PR method already in use in another country. In fact, most democracies use some form of PR. The four systems in common use are MMP (Mixed Member Proportional), STV (Single Transferable Vote), open party list and closed party list.

Of these four, closed party list is the easiest to dismiss as a possibility for America. Like any PR method it solves most wasted votes, and it can offer interesting guarantees on issues like gender balance, but it hands over most of the power in deciding who’s elected to the parties’ internal bureaucracy, something Americans simply wouldn’t put up with. And open party list is a little bit better, but is still probably too party-centric for this country.

The basic idea of STV, used in countries like Ireland or (for a few cases) Australia, is to ensure each vote counts by passing it from candidate to candidate until it makes a difference. In technical terms, the system ensures that winning takes a certain amount of votes — the “Droop quota” I mentioned above—leaving only a small remnant of wasted votes less than a single Droop quota. In order for that to work, voters have to put a large list of candidates in order of preference, marking a 1 next to their favorite, a 2 next to their second choice, and so on. In America, this would probably happen in districts of around 5 candidates each, so your ballot would list up to 5 times as many candidates as you see now, and your job would be to evaluate all of them and rank them in preference order.

In fact, STV is used in 2 places in the US today: in Cambridge, MA for the city council, and in Minneapolis, MN for the parks commission. I happen to live in Cambridge, because I’m a PhD student at Harvard. On November 8th, I’ll get a ballot with 26 candidates and 3 slots for write-ins, and be asked to put them in order from 1 to 29 (though in practice there’s no chance that anything below rank 18 will count). I’m a huge elections geek, but even for me researching and ranking all 26 candidates is a daunting task. And indeed, for a sizeable minority of even those who show up to vote in the odd-year Cambridge muni elections, it seems that ranking just their top choice is all they can be bothered to do. I think that this complexity is a real barrier to STV catching on as a popular method in the US.

That leaves MMP, a hybrid voting method where districts are enlarged somewhat to leave some leftover non-district seats. Then, some representatives are elected by districts, and others are assigned by party to balance out the proportions. This is an excellent method for countries that use it, such as Germany and New Zealand. But in a federal system that mixes small and large states, it’s nearly impossible to make all the numbers balance out right without raising constitutional questions of state sovereignty. And real voter choice is actually a bit more limited than under our current method, with the remaining power effectively reverting to the parties — which, as with party list methods, probably wouldn’t sit well with American voters.

Furthermore, every one of the methods above faces a hurdle I haven’t mentioned yet: incumbents. Like it or not, any method that’s strongly opposed by incumbent politicians probably won’t pass. Any of the above methods would involve a disruptive transition, where large numbers of incumbents could lose their seats.

So, in order to be realistic, a solution to this problem should be able to appeal to the majority of voters whose votes are wasted under the current voting method; to most incumbents from at least one of the two major political parties; and, ideally, also to those eligible voters who have decided not to participate in politics for lack of meaningful options. In other words, it should solve the problem of wasted votes, without creating new problems with ballot complexity, unaccountable party insiders or disruptive transitions.

That’s an engineering problem, but with a modern understanding of social choice, game theory, and mechanism design, it’s a very solvable one. I have a specific proposal I call PLACE voting (for Proportional, Locally-Accountable, Candidate Endorsement), which I’ll describe below. I’m not the only one who has good ideas for resolving these issues. In Canada, there are similar proposals like “Local PR” and “Heart and Head,” among others. My own proposal is inspired by extensive discussion with other voting theorists here in the US in venues such as the Electorama email list or the EndFPTP slack channel and reddit.

PLACE voting summary

Here’s a quick summary of how PLACE voting would work. (If you want more finicky details, you can read my earlier article or the technical description.)

- Your ballot would list the candidates in your district. You could either choose one or write in a candidate from another district.

- Unless you opt out, your ballot would then be “delegated” to your chosen candidate. He or she will have previously publicly declared a slate of other endorsed candidates within his or her party, so that if he or she is eliminated, your vote will transfer to another candidate on that slate. (Within the slate, transfers happen in order of direct votes. If the whole slate is eliminated, the ballot goes on to other unendorsed members of the same party, and then to endorsed candidates from other parties.)

- The transfer process would work in a way (based on STV) that ensures that there would be exactly one winner per district (one of the top two in that district), and also minimizes wasted votes.

- Once winners were chosen from each district, they would be given “extra territory” so that each district is in the overlapping territories of one winner per winning party.

Advantages of PLACE

This method has several advantages, aside from fixing gerrymandering and minimizing wasted votes.

- Ballot format is basically familiar, and quite simple. The only possibly new aspects are a write-in slot and a (relatively unimportant, except for constitutional reasons) “do not delegate” option.

- By the same token, it’s easy to simulate the result of past elections, assuming that voters would have voted similarly to the actual election. This can reassure both voters and politicians that the results are reasonable — basically the same as FPTP, only more proportional. Note that since gerrymandering tends to favor Republicans overall, a more-proportional result will also be more Democratic.

- Candidates with a particular connection to a particular community or set of issues could pull in votes from across the state. This would encourage higher turnout and increase minority representation. Even if a particular candidate like that got not enough (or significantly more than enough) votes to win, any votes which didn’t go to elect them would be transferred to other candidates they’d endorsed. Thus they could use those endorsements to make sure that their votes continued to support candidates sympathetic to their community or interest group. Thus, the voting method itself would help minority groups organize and strengthen the voice of their leaders.

- Representation is still local, and this method is compatible with all existing US law (including the 1967 federal statute requiring single-member districts).

- Candidates are individually accountable to voters, and voters in practice have the power to throw out even well-ensconced party insiders.

Let’s say you agree that this is a great idea. Is it feasible?

Yes. PR could be implemented at three different levels — local, state or national. Though it would face legal challenges, most experts agree that it would pass muster from a constitutional basis. Fighting this battle at the local or state level is worthy, but tough; the very places that have the biggest problem with gerrymandering are, by the same token, the places where the opposition will be the most powerful. So really, the big prize is national reform.

At the national level, gerrymandering has a clear pro-Republican bias, so a fairer PR method is in the interests of Democrats. Democrats probably won’t get the power to pass controversial legislation before 2021, when Trump (or Pence, or Ryan, or whoever) will lose his veto power. But it’s quite possible that in the 2020 elections, an anti-Trump wave could give Democrats control of both houses of Congress and the White House, despite their built-in disadvantage from gerrymandering. If that happens, they will probably be in the mood to look for real solutions, even unconventional ones, for the structural disadvantages they’ve been facing.

So 2021 is the target. Before that time, we have to get these ideas talked about more broadly, and ideally tested out at some lower level of government. People like me need to run more simulations of how PLACE would have worked in past elections; wonks and activists need time to process and discuss and refine these ideas; and we need to build grassroots support among all the various disparate groups of voters who would benefit from this—Democrats, third-party supporters, independents, moderate Republicans and disengaged voters, especially those from minority ethnic or interest groups.

What you can do

Congratulations! If you’ve read this far, you’re probably a bit of a nerd…um…wonk, like me. So what can you do?

Well, if you’re involved in this issue on a professional level, I want to talk to you. Email me — my address is Jameson.Quinn@gmail.com.

You can also get involved with electology.org, a smart nonprofit that focuses on voting reform. (Full disclosure: I’m on the board.) For now, we’re mainly working on single-winner stuff, but campaigns for PR reform could be in our future. (Note: in this article, I’ve embraced partisan tactics for passing PR; but PR itself is a nonpartisan idea and electology.org is an explicitly nonpartisan organization. This article speaks for me, not for them.)

If you’re active with some group that deals with voting rights — whether it’s Common Cause, the Brennan Center, Demos, NAACP or MALDEF, the Sightline Institute, a local League of Women Voters, FairVote or even the Democratic Party—you can encourage them to take a look at PLACE voting and at the game plan above. Wasted votes might not seem as viscerally unjust as literal disenfranchisement, but the impact in political terms is the same; and a 7% gerrymandering gap represents over 10 million votes of partisan distortion.

Together, we can do this!