Greece Crosses the Rubicon: Massive “No” Vote Endangers its Eurozone Membership

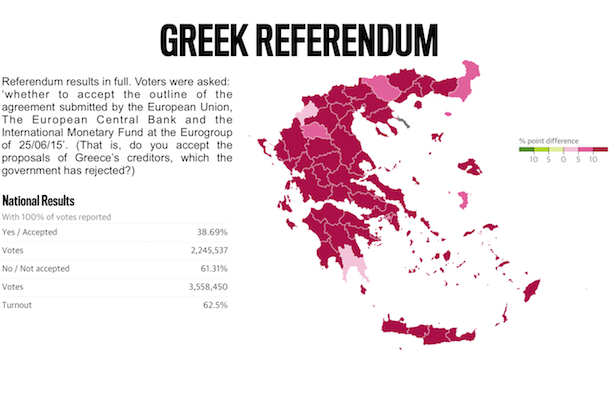

Greece crossed a political-economic Rubicon on Sunday, 05 July 2015, by holding a national referendum on the “troika” (European Commission, European Central Bank, and IMF) five year-long financial strategy. The so-called Greferendum’s “No” vote, which rejected the lenders’ plan for debt financing and structural reforms, was overwhelming supported by the Greek electorate (61.31% in favor of “No”). The “Yes” vote (38.69%) communicated support for the “troika” approach.

The 62.50% turnout is notable but not particularly high considering the importance of the question. It is likely that the very short time allowed between the referendum and its announcement, suppressed participation. In absolute terms, then, 38.31% of the Greek electorate (that is, the 61.31% “No” vote of the 62.50% participation rate) stood up and rejected what the Greek government cast as a disastrous and predatory “troika” program. Importantly, the result upsets many of our conventional readings of Greece’s electoral geography.

The map of the referendum results is truly striking:

In the far northeast electoral district of Alexandroupolis the “No” vote was 58.79%. It is a medium-sized city on the Greek-Turkish border on the Aegean Sea littoral, the economy of which relies substantially on the public sector, and has commonly voted for one of the two establishment parties, now in opposition. Its proximity to Greece’s main geopolitical rival, Turkey, has always guaranteed that the region would follow status-quo parties. Home to many military retirees, one would have expected stronger support for the “Yes” option, after a long list of retired generals and admirals came out in favor of “Yes.” In the conservative Grevena district, in Greece’s mountainous, relatively isolated, and economically marginalized interior, the “No” vote amounted to 55.09%. The allure of historic European regional development funding and Common Agricultural Policy supports did not appear to have played a significant role in the voters’ political calculus. Even Laconia, of Sparta fame, a reliably conservative region that has commonly voted for right of center parties, was unable to see itself voting for “Yes,” delivering albeit marginal support for “No” (51.17%). At the other end of the global connectivity spectrum, cosmopolitan resort district Mykonos supported the “No” vote at approximately the same level (54.77%). Surprisingly, perhaps, in the equally cosmopolitan Prefecture of Corfu, the “No” option received 71.17% of the vote, a rate similar to those delivered by Greece’s poorest urban districts.

As expected, support for “No” was extraordinarily high in electoral districts where the Left traditionally prevails: The electoral districts of the Prefecture of Crete approved the “No” option at the rate of 69.87%.

Greece’s major population centers, Athens and Thessaloniki, also reflected the national mood: The “No” option received massive support in Athens’ metropolitan region electoral districts, which have traditionally voted for parties of the center-left and left, and have suffered very high rates of unemployment, since the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis: In descending order, Aspropyrgos: 79.20%, Fyli: 77.22%, Perama: 76.64%, Acharnes: 75.25%, Keratsini-Drapetsona: 72.84%, Agia Varvara: 72.75%, Nikaia-Agios Ioannis: 72.61%, Eleusina: 71.88%, Laureotiki: 71.81%, Tauros: 71.28%, Aigaleo: 70.68%, and Peristeri: 70.31% (all in the Prefecture of Attica).

One has to go to the absolutely wealthiest electoral districts of suburban Athens to find any support for the “Yes” option: Mansion-adorned Ekali lent its support at a rate of 84.62%, Dionysus at 69.78%, yachtsmens’ playground Vouliagmeni came in at 66.27%, old-money Kifissia at 64.59%, Drosia at 65.42%, and Voula at 63.88% in support of “Yes.” In Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, only the posh suburban electoral district of Panorama voted in favor of “Yes” (62.68%). The contiguous district of Pylaia supported the “No” option at the rate of 56.64%.

The traditional cleavages of Left-Right as representing socially progressive v. bourgeois-fiscally conservative perspectives, at least in this instance, appear to have broken down. The crisis has clearly annihilated much of the working class, pushing it under the official EU poverty level (28% of Greece’s population deemed to be at-risk-of poverty with household income inferior to 5,023 euros. The EU mean is 16.7% – Source: Eurostat, 2013). Importantly, it appears to have also annihilated the middle class, which no longer trusts establishment parties like New Democracy and PASOK, which alternated in power between 1974 and 25 January 2015. The crisis as bulldozer…

Much work remains to elucidate the apparent realignment of Greece’s electoral landscape, especially with regard to voter mobility toward the governing radical left SYRIZA Party. It is unclear whether this shift represents the first move toward a durable transformation of regional electoral politics, or whether it is a reflection of the peculiar circumstances of this quick referendum, held under extraordinary pressure. In the end, the outcome of this latest chapter of the Greek crisis would entirely depend on how the Tsipras government and SYRIZA, might want to use the extraordinary mandate that Greek voters lavished upon them.

In spite of its many public pronouncements, we still have a limited understanding of SYRIZA as a governing party. Although its progenitor, the Communist Party of Greece, so-called “of the interior” (meaning of the Euro-communist variety) has existed as a legal party since 1974, SYRIZA as the reformed and formal successor of it, is a recent creation. Only in 2012 did SYRIZA crystalize into a conventionally led party under Tsipras, and that for the purpose of participating in the two national elections of that year. Before 2012, it commonly attracted only about 4-5% of the national vote.

SYRIZA stands for “Coalition of the Radical Left” (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς, Synaspismós Rizospastikís Aristerás) and represents a spectrum of ideologies of the left, some fully anti-establishment, and anti-EU, others closer to what we would recognize as social-democratic ones. Although Tsipras is the party leader, it is understood that the party contains a number of ideological vectors championed by members of the party’s central committee. Panayiotis Lafazanis, currently serving as government Minister of Productive Reconstruction, Environment, and Energy, is considered an anti-EU hardliner, and a potential challenger to Tsipras. We should best think of SYRIZA as a coalition of power centers, which have at least ephemerally come together to contest Greece’s political status quo. Otherwise, the intra-party decision-making process is opaque to us.

This week, under financial structural stress, SYRIZA may reveal its partisan fissures to the world. I expect that we might know a lot more about the ordering of ideological strands in SYRIZA by Sunday, 12 July, when the European Union will hold a summit to decide on the viability of the to-date not submitted Greek plans. On the 20th of July at the latest – a key date in the Greece-EU relationship, in which Greece is expected to disburse a considerable amount of money to its creditors–we will know if PM Tsipras ever intended for Greece to stay in the Eurozone.

The Scenarios

The jury is out on what that the referendum ultimately signifies. Ultimately, I believe it was a disastrous move by Tsipras, which communicates to many that his commitment to the European project might not be firm. Some claim that he is committed to taking Greece out of the Eurozone.

The best-case scenario would be to take Tsipras government at its word: that it is negotiating in good faith, albeit espousing an unconventional view of statecraft and diplomacy. It is undertaking actions that it hopes will bring forth not just a deal with the troika but a better deal than the one presented to it on the 25th of June. In brief, in this scenario SYRIZA genuinely desires a deal within the Eurozone, and is willing to bring the negotiation to a conclusion that will preserve Greece’s position in the Eurozone and the European Union, even if it would damage its standing in the volatile Greek political scene.

The worst-case scenario is that the Tsipras Government is not negotiating in good faith and has no real interest in a deal within the European frame. Instead, it might desire to fully inherit the hemorrhaging clientelistic state that corrupt conservative and social-democratic governments of the past birthed. The tortured negotiation and finally the resounding “No” vote in the referendum provide it with a pretext for a break with the EU. How would that make sense? European regulation is killing the clientelistic state, by stemming the flow of low-interest EU finance capital, while, granted, also strangulating Greece’s poor and middle class that are instruments and victims of that clientelistic state. To preserve it, Tsipras needs to take it out of the euro (in extremis, even out of the EU) to maintain the ‘votes for perks’ system.

And then, there is this tangent scenario that describes the Tsipras government as radical performance art project, its members sans cravats, wearing flip-flops to solemn Parliament meetings, dispensing with centuries-old diplomatic etiquette, courtesies, and protocols, treating the European political theater as a student sit-in, or occupy demonstration, and calling the lenders and European officials terrorists. It is a distinctly non-realist approach to the conduct of international relations. It gives us pause, because it does not adhere to what we understand as the effective art of diplomacy.

There are significant issues with the Greek government’s negotiation narrative:

- European and IMF partners are treated as enemies, adversaries and terrorists. They are systematically accused of conspiring against, and profiting from, the misery of the Greek people.

- Lip service is paid to Europeanism but also disdain is demonstrated for substantive dimensions of the European project, its regulations, and mechanisms.

- The Greek government claims to be defending the sovereignty of the Greek state, when it is patent that membership in the European Union entails substantial sovereignty concessions. That claim sells extremely well among nationalists, especially the coalition partner Independent Greeks.

- Refusing to negotiate at the technocratic level and insisting on political solutions, it intends to contravene or bypass EU regulatory frames.

- The Hellenic democracy is held up as exceptional, entirely neglecting that all partner states are also democratic and accountable to their electorates.

- Its only referendum partners included the rightists-nationalists-anti-immigrant Independent Greeks, and the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, the members of which have been indicted for operating as an organized crime organization.

I by no means dismiss the tactics or deride practitioners of such unconventional tactics, because at the end of the day, what matters are results. If the intended result is a return to prosperity in terms of the EU political, regulatory, and economic conventions, then the Tsipras strategy and tactics are disastrous. If the intended result is a big break with the EU—regardless of whether it is over neoliberalism and markets dominance, austerity, or to assume control of the Greek state’s clientelistic culture—the strategy and tactics are spot on.

In all this we are at risk of missing what this negotiation means for the Greek people. Scenes of elderly pensioners sobbing in ATM lines are not staged. The unemployment rate is the highest in the European Union, and at 63% for the 18-25 age cohort. You need hospitalization? Make sure you bring your own sheets and gauze. It is not everywhere like that, but it is in too many places to dismiss it as sensationalism. So, who is to blame? IMF structural reform plans are notable for their callous disregard for the social state. The European Union is a potent agent of neoliberalism and globalization, in spite of its “Cohesion” and “Solidarity” discourses and policies. As for Greece, it has been for years a ‘court of miracles,’ where state-pensioned seeing-impaired persons drive taxis and urban hospitals without grounds employ gardeners by the dozen – circumstances that found the government and many of its citizens in a political embrace that precipitated the looting of Greece. So, there is much blame to go around. So-called “Grexit” is unlikely to resolve any of it, as long as corruption and clientelism are rife in Greece. Instead a European solution needs to be crafted for Greece’s national crisis rendered international through the global financial crisis of 2008.

Drawing on the experience of the last two weeks, I am concerned that the Tsipras government is not committed to the European project and a solution in the European frame, and intends to take Greece out of the Eurozone. I sincerely hope I am wrong.