Books

H.G. Wells and Defending the ‘Restoration Doctrine’

Michael Singh’s parochial critique in Foreign Policy Magazine entitled “Restoration’ is Not an Option: Why America Can’t Afford to Lead From Behind,” attacks Richard N. Haass’s idea of a “Restoration Doctrine,” which in essence is “a U.S. foreign policy based on restoring this country’s strength and replenishing its resources—economic, human and physical.”

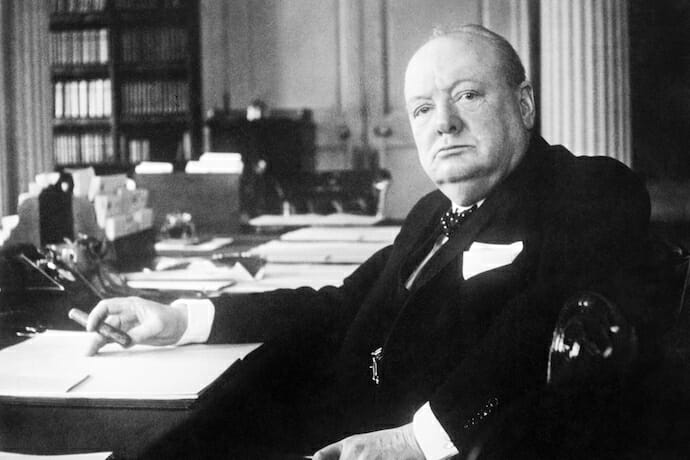

Singh’s reproach is reminiscent of Winston Churchill’s response to an H.G. Wells’ article penned in 1923, in which he argues for an end of the British Empire and a system of world federal government. A staunch defender of the political status quo, Churchill dismissively replied to the suggestion. “We see him (Wells) airily discarding, or melting down, all those props and guard rails on which the population of this crowded and precariously conditioned island have been accustomed to rely…We can almost hear him smacking his lips at every symptom or upheaval in India or in Africa.” In a sense, this is also Singh’s main point of critique. He attributes a certain naiveté, fit for an unrealistic dreamer – not a policy expert – to Haass’s “Restoration Doctrine.”

Singh criticizes the supposed sequentialism of Haass doctrine with domestic policy first and foreign policy second. Additionally, according to Singh, Haass suggests the United States disengage in an isolationist manner akin to pre-1941 times by conducting a more modest foreign policy. In Singh’s logic, forward deployment, democracy promotion, and free trade are the first lines of defense of the world’s greatest power. Overall, there is no need for much strategic change–especially a doctrinaire shift.

Singh’s thinking seems to be dominated by a unilateral mindset. A gradual decline of the U.S. is inevitable since we are moving towards a more multi-polar world – a decline largely triggered by a wider distribution of power within the system. Whether Brazil, China, or India will ever catch up with the U.S. is secondary. Haass’s new doctrine, therefore, blows a fresh wind into the faces of those who tend to ignore the tremendous shifts of power occurring in the world and the relative and absolute gradual decline of Western influence.

Isolationism is certainly no healthy policy for a great power, but neither are tremendously expensive military adventures funded through credit from abroad and costing the lives of thousands of young Americans for no clear objective. Singh concludes his piece: “America achieves greatness by setting ourselves to great tasks with great conviction; now is a time to streamline our budgets, programs, and expenses, but not our ambitions in the world.” This is a non-sequitur; one can have ambitions, an ardent desire for rank, and power, but seldom is this reconcilable with balanced budgets and realist foreign policies; after all, ambitions in a democracy need to be fuelled by oversimplifications and often alarmist statements, which lead the country “abroad, in search of monsters to destroy,” to quote John Quincy Adams.

It is also common for commentators such as Singh to equate the growth of democratic government and liberal capitalism with a simultaneous growth of U.S. influence in the world. In pure power politics, this is not true. For example, the European Union quietly has been more successful in the last 20 years than the United States in expanding democracy and liberal capitalism by peaceful means – a fact rarely mentioned among Washington’s policy makers.

While beating a dead horse with analogies to the British Empire (let alone the Roman Empire!), it is telling that political analysts, scholars, and commentators continuously raise the subject of American decline, debating the nature of America’s status in the world and its foreign relations. The debate itself is affirmative of at least the uncertainty that many politicians and foreign policy makers feel about the future of the United States as the leading great power of the 21st century.

“We cannot alone act as the policeman of the world!” These words were not uttered by a U.S. President or Washingtonian policy maker but by Andrew Bonar Law, British Prime Minister in 1922, attempting to calm the voices of imperial expansion within Great Britain. Short-time presidential contender Donald Trump uttered the same words verbatim when discussing the U.S. engagement in Libya (followed by “I’d just take their oil!”).

Current debates on decline are reminiscent of the debates in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s – of course, only ostensibly. What is similar, however, is that from Joseph Chamberlain to Winston Churchill, it took the good first half of the 20th century for British political leaders to finally accept the abandonment of imperial schemes in a changed world. It will also take U.S. commentators and politicians a couple of decades to genuinely acknowledge a new reality (the process only started in the 1970s).

Paying lip service to phrases such as President Obama’s “The era of U.S. unilateralism is over” without offering new policy prescriptions of how the United States can best weather this new climate is ludicrous at best and dangerous as worst. Multi-polarity is a fact. The world will be increasingly less interested in U.S. ambitions and resources even if liberal democracy is the way of the future.

Singh is therefore wrong to criticize Haass for arguing that the U.S. cannot shape the international system by retrenchment and the adaptation of a restoration doctrine. In the long run, the United States will have a tougher time achieving its foreign policy objectives, not because of any particular policy, but because of the uncertainty and wider distribution of power that accompanies a multi-polar world. A restoration doctrine will lead to a more careful husbanding of resources and a slower, more ‘elegant decline’; Singh’s idea of continuing foreign engagement will lead to a more rapid fall. In that respect, the absence of concrete agendas rather than a belief in the undying strength of the United States will be the true mark of reactionaries in the future.

In early 20th century Great Britain, anti -imperialist commentators and politicians were often thought to be affected by the parochial disease of “Little Englandism” – foreign policy solely focused on the well being of the British Isles at the expense of the empire – essentially an euphemism for isolationism. Yet like the propagators of “Little Englandism” –Richard Haass does not believe active engagement beyond national borders is unimportant; rather he believes that the chief threat to the United States comes from internal domestic weakness; not from more distant enemies.

The Churchill – H.G. Wells-esque debate of Haass and Singh on the future of the country will continue in the United States – indeed in the West – for some time. As stated before, however, that the debate is happening alone is already indicative of what the future may hold. In one of his lectures, the German philosopher Georg Friedrich Hegel reminisces about the predictive power of philosophy: “One more word about teaching what the world ought to be: Philosophy always arrives too late to do any such teaching…”

The same can be said about sound foreign policy advice. Once we recognize the writing on the wall it might very well be too late although Haass appears to be more aware than most policy makers of what the future will hold.