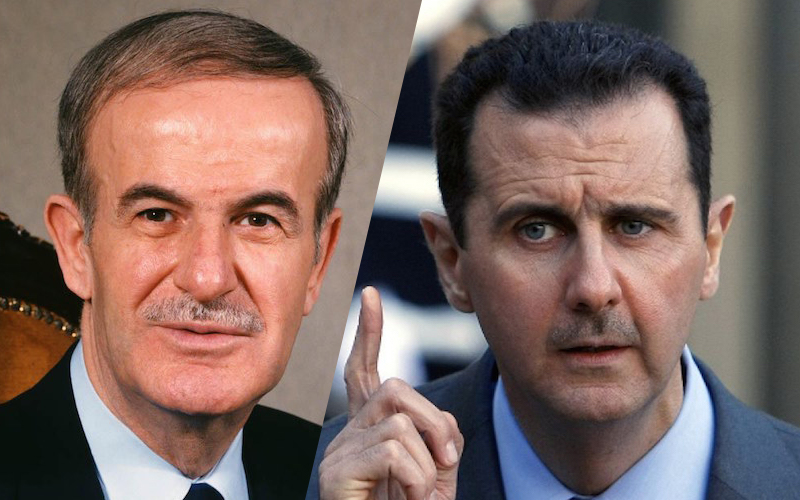

Hafez al-Assad, Controlling Syria from the Grave

Syria’s fate changed drastically on June 10, 2000, the day Hafez al-Assad succumbed to a heart attack in Damascus. The Lion of Damascus was no more. Left behind was a carefully constructed authoritarian structure that had sustained three decades of unrivaled power in Syria. Hafez al Assad’s most enduring legacies knit together the Alawite community and other minorities. He acquiesced to the Sunni elite, created an effective secret services, and most of all appointed the next ruler of Syria, the quiet, multilingual, tech savvy ophthalmologist, Bashar al-Assad. The Assad legacy assisted Bashar in holding on to power even as his contemporary authoritarian rulers succumbed to the whirlpool that was/is the Arab Spring.

Syria is at the heart of a conflict that has irreversibly changed the politics of the Middle East. While most other authoritarian regimes dwindled and eventually collapsed, the Assad regime has proven to be, to the surprise of many, relatively steadfast. The survival of the Assad regime despite a full throttle pro- democracy movement and a brutal, lengthy civil war can be explained by the institutional and strategic strengths the regime enjoys. Loyalty of the Army, a mandate from minorities and moderates who fear an Islamist takeover, constant support from the Sunni elite, and military backing from Iran and Russia have enabled the Assad regime to stand firm against all odds. The unrelenting claim to the throne is reflective of the legacy of authoritarianism in Syria.

Assad’s regime, much like his father’s, is a regime of minorities. Governing a Sunni population of over 74%, the Assad family belongs to a Shiite ethno-religious sect called the Alawites. The Alawites bear a peculiar, troubling history as a minority. Not only is there religious tension between the Shiite and Sunni sects of Islam, the Alawites are viewed pejoratively also by the fellow Shiite groups for having ‘heretical’ tendencies. They are a minority within a minority.

In an identity conscious society like Syria’s, the ethno-religious divisions are barely forgotten and rarely do they lose significance. Apart from the Sunni – Shiite division, Syria also hosts a considerable population of other minorities which include, among others, Christians, Jews, Kurds, and Druze. Syrians of different religious traditions speak the same language, share ancestral legacy and yet the identity politics of ethnicity and religion almost always plays a significant part in Syrian polity.

A central element of the Syrian authoritarian structure is the support it receives from a coalition of all minorities. In a typical act of self- preservation the minorities have historically lent support to the regime for any alternatives that would place them at a great disadvantage, physically and economically. Assad’s regime, from the time of Hafez al-Assad till this day, enjoys unwavering support from the minorities for it is viewed as a protector of minority interests in Syria, and the regime itself belongs to a minority.

The carefully engineered minority domination in the bureaucracy and the army has ensured that defections remain at a bare minimum. Unlike the fragile regimes of Muammar Gaddafi, Hosseini Mubarak and Ben Ali, the state apparatus and the army have stood by the Syrian regime, mostly for self- preservation purposes. The network of minority domination that exists in Syria is pure genius in that the minorities not only lend protection to the Assad family but to each other as well. It is a typical example of mutual protection. In Libya, for example, the weakened state institutions were exclusive of each other working mostly as separate entities protecting the interests of the ruler, Gaddafi, and of those close to him. Such a system of weak interdependence was bound to fail simply because the state apparatus had no existential stake in protecting the regime once trouble hit the shores of Libya. In Syria the case is exactly to the contrary.

Fearing the rise of an Islamist regime, the moderates and secularists provide another social, intellectual support base to the Assad regime. The Assad regimes (Hafez’ and Assad’s) have been responsible for employing a forceful, uncompromising policy of secularization from above, a policy that turned brutally violent in the 1980’s. Bashar Assad, more than his father, placated the moderate Sunni population through exhibiting deference to ‘cultural’ Islam. The state policy, however, actively conducted a purge of all radical Islamic political voices within the Syrian political space, mostly under the banner of secularism.

The fear of an Islamist regime replacing Assad, even democratically, is corroborated by the political developments in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt. In each of these countries the suppressed Islamist movements ran underground networks and with their impeccably organized campaign gained immediate momentum after the old regimes collapsed. Libya has deteriorated into an even bloodier civil war and has become a second home to the Islamic State. Egypt, in the first free elections in her millennia old history elected a government that was overtly sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood. The situation in Tunisia is slightly more optimistic, though not enough to be called a success. The National Transitional Council continues to struggle in reconciling with the well mobilized Islamist voices.

Furthermore, the emergence of an ideologically comprehensive, militarily prepared, bureaucratically advanced terrorist organization, the Islamic State, has drastically empowered the position of the Assad regime. Based in Raqqa, a city in northern Syria and the administrative capital of the Islamic State, the terrorist group looms over Syria like a vulture over its prey. For many players in the middle east, especially the west, the choice between battling IS and fighting Assad is imminent.

The rise of the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian offshoot of Al Qaeda, which together hold around one third of Syria could not have come at a better time for the Assad regime. With the recent Russian air strikes targeting strong rebel holds, the only force capable of fighting the IS is the Syrian Army. The ability to devote ground troops in the fight against IS has inevitably increased the relevance of the Assad regime in the ongoing conflict.

Also, given the strategic strengths of the Assad regime, the prospect of relinquishing control seems bleak. Thus, a choice remains to be made on the part of the western allies, whether to indulge Assad in the solution or continue fighting him through proxies pushing Syria further into a longer, deadlier civil war. Syria is infinitely volatile, unprecedentedly fractured, and worryingly armed. Allowing a power vacuum to emerge in Syria will be repeating the worst mistakes of Afghanistan, it will mean setting Syria en route a bloodier disintegration.

Bashar al-Assad on the evening he assumed power delivered a promising speech, one that filled the hearts and minds of an oppressed people. Finally change had arrived many thought. The young President became the cause of raised expectations all across Syria, the expectations that his regime obviously dashed to pieces. There is only one thing I’ve certainly concluded through my research on the Syrian regime. The London educated, liberal minded Bashar al-Assad was barely ever in control of Syria. The Syrian regime was indeed controlled by the legacy of Hafez al-Assad of which Bashar is only a part. The social bases and sources of support that have ensured the regime’s survival were engineered by Hafez Assad’s regime. All that was ever expected of Bashar al-Assad, the heir to the Assad legacy, was to not undo those alliances.