Books

‘Hi Hitler!’: The Normalization of Nazism

Originally mocked, subsequently feared, posthumously vilified, Adolf Hitler today is becoming normalized. Throughout the Western world, the Nazi dictator has long been regarded as the epitome of evil. But since the turn of the millennium, he has been increasingly transformed into a more ambiguous figure. Nowhere is this transformation clearer than on the Internet. Anyone who conducts a simple image search of Hitler on the World Wide Web will encounter an eclectic array of representations, ranging from archival photographs documenting the dictator’s role in the Third Reich to digitally altered images that spoof him for laughs. The diversity of images is striking, but what is most notable is how the line separating them is beginning to blur. As discerning web users probably know, certain photographs of Hitler are now doing double duty, serving the purpose of both documentation and exploitation.

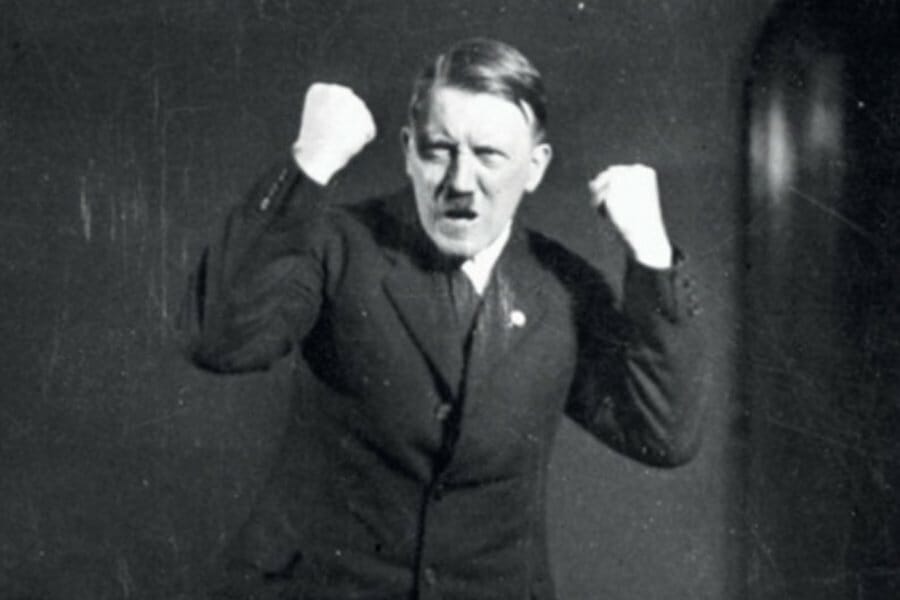

Consider the photograph below of Hitler, taken by his personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann in 1927, in his Munich studio in 1927, it is one of a famous series of photographs that portray the then struggling Nazi party leader meticulously practicing his oratorical choreography.

The photograph depicts Hitler in a pose of fanatical intensity, his fists clenched, his face contorted in an expression of fury about what we can only imagine was one of the countless grievances that fueled his political agenda. As a document of history, the photograph is significant for showing how Hitler methodically rehearsed what were widely thought to be “spontaneous” gestures, a fact that explains why the Nazi party leader, eager to protect his image as a “naturally” gifted orator, forbade the image – and the entire series of which it was part – from being shown to the German public during his lifetime.

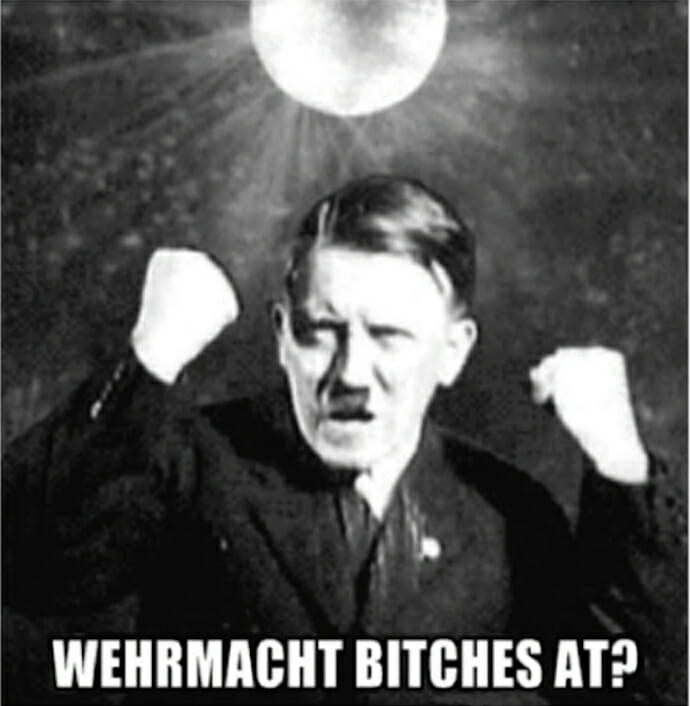

Hoffmann’s photograph is not merely a document of history, however, but a document of memory thanks to its recent transformation on the Internet. More than eighty years after it was originally taken, Hoffmann’s photo appeared on the popular website, Meme Generator, having been dramatically altered by the addition of a 1970s-style mirror ball over the Nazi dictator’s head. The mashup image, called “Disco Hitler,” radically subverts the original photograph’s intended purpose of portraying the Nazi leader as a passionate politician by satirically depicting him as a dexterous dancer. The transfiguration does not stop there, however. Meme Generator allows web users to add humorous captions to the digitally altered image, thereby transforming it into an “image macro.” The term may not be familiar to average readers, but image macros are a staple of contemporary internet culture. Comprised of photographs with superimposed texts rendered in (by now ubiquitous) Impact font, image macros seek to make people laugh by juxtaposing images and texts in ironic, incongruous, or absurd combinations. Many such images have proliferated on Internet websites, forums, and imageboards in recent years – so much so, that image macros have risen to the status of Internet “memes,” ideas that have spread virally and achieved iconic status on the World Wide Web.

“Disco Hitler” is one of the more popular image macros of the Nazi dictator on the Internet, with nearly three thousand currently in existence on Meme Generator alone. Although their captions appear in many different languages, all of them strive to be humorous, albeit in different ways. Some seek laughs by employing crude puns and occasional German words, for instance: “Disco Hitler Says Stalin Alive!” and “Wehrmacht Bitches At?” Others end up offending rather than amusing, as with the tasteless phrases: “I Said ‘A Glass of Juice,’ Not Gas the Jews!” and “Six Million! New High Score!” Still other captions veer toward the absurd, as with “I Did It for the Lulz.”

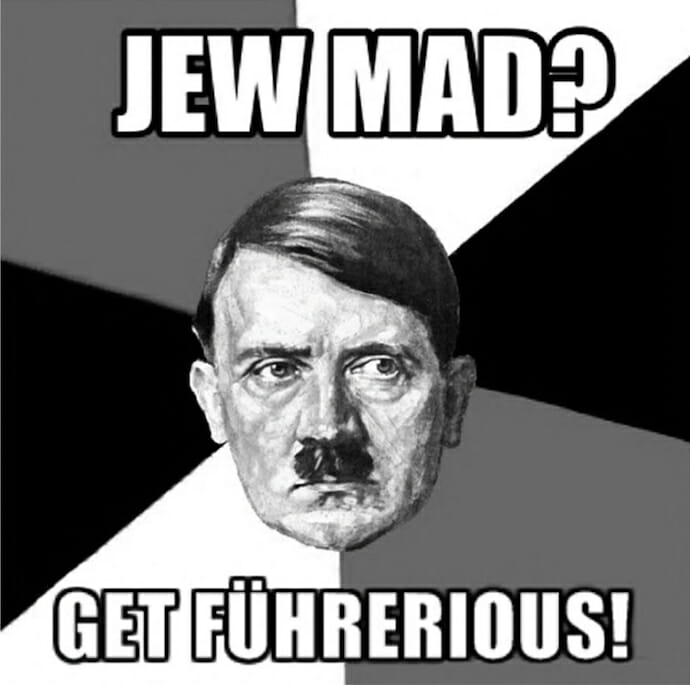

These and countless other versions of “Disco Hitler” are merely a tiny fraction of the myriad image macros that poke fun at the Nazi dictator on the Internet. An estimated 61,000 Hitler-related image macros are currently listed on Meme Generator and thousands more exist on competing meme-generating sites. They include the ever-popular “Advice Hitler” (a knock-off of the famous “Advice Dog” meme), which features the Nazi dictator’s disembodied head – set against the backdrop of a black, white, and red color wheel – dispensing words of bad “advice.” There is “Bedtime Hitler,” depicting a pajama-clad Führer riding a toboggan across a night-time sky. There is “Chilling Hitler,” which shows the dictator relaxing with a newspaper on a patio chair in Berchtesgaden. There are even image macros of Hitler’s head photoshopped onto the bodies of supermodels, pop singers, and rappers. Like “Disco Hitler,” all of these images have also been supplied with user-generated captions meant to elicit laughs.

Among the many captions that have accompanied these images, one of the most memorable is “Hi Hitler!” The phrase has appeared in the “Disco Hitler” and “Advice Hitler” memes, as well as in other offshoots, including parodies of the Pokemon character Pikachu; spoofs of vintage British posters (“Keep Calm and Hi Hitler”); and photographs of sundry house pets. At first glance, the phrase “Hi Hitler!” may seem banal. Read at the literal level, the phrase merely extends a greeting – a colloquial version of the word “hello” – to an image of the Nazi dictator. At a deeper level, however, the phrase contains a more satirical message. As even moderately informed web users know, the exclamation “Hi Hitler!” is a corruption of the infamous Nazi salutation, “Heil Hitler!” (“Hail Hitler”). This German slogan was originally coined in the early 1920s to buttress the cult of personality known as the “Führer myth.” In its more recent incarnation, however, the slogan’s original meaning has been inverted. The substitution of the casual English word “hi” for the more grandiose German word “heil” punctures the Nazi salutation’s pomposity and renders it laughable. The humorous effect is further enhanced by the ambiguity of whether or not the mangling of the original salutation is intentional. In all probability, the phrase “Hi Hitler!” has spread on the Internet due to the efforts of savvy web users who appreciate a good pun. Yet there is anecdotal evidence that certain people, ignorant of German, have mistaken the original German “heil” for the English “hi,” and naively believe that “Hi Hitler” represents a historically authentic phrase. In reproducing and circulating it, therefore, they have added to its humor by unintentionally committing a malapropism.

The phrase “Hi Hitler!” is notable not merely for being funny, however, but for symbolizing a new trend in the representation of Nazism. In an ironic turnabout – indeed, in what might be regarded as a bizarre form of deferred justice – the politician who insisted on maintaining complete control over his public image during his lifetime has, of late, been subjected to infinite forms of digital distortion. Thanks to the Internet, Hitler has been transformed into a meme in his own right. Beyond appearing in countless image macros, he has starred in thousands of satirical movie and music videos; he has been featured in Web-based comic strips; he has been profiled in mock encyclopedia entries; he has even inspired online games. In light of this trend, the phrase “Hi Hitler!” can be interpreted as a gesture of welcome to a radically new view of the Nazi dictator – one that regards him as a symbol of humor instead of horror.

The increasingly comic representation of Hitler on the Internet is part of a larger shift currently underway in the memory of the Nazi past. Since the turn of the millennium, the traditional belief throughout much of the Western world that the Third Reich should be remembered from a moralistic perspective has been challenged by a powerful wave of normalization. This wave has manifested itself in many areas of contemporary intellectual and cultural life. It has appeared in sophisticated works of academic scholarship and journalism; in popular novels and short stories; in works of film and television; and, most prominently, on innumerable Internet websites. Whether aiming high or low, all of these works have transformed the Third Reich in different ways. Some have relativized it in order to minimize its historical distinctiveness. Others have universalized it in order to emphasize its alleged relevance for contemporary issues. Still others have aestheticized it through unconventional means of representation. The works comprising this trend have appeared in many different nations, whether in Europe, North America, or the non-Western world. They have reflected diverse motives, ranging from the political to the puerile. This diversity notwithstanding, the normalizing wave has generally focused on a single goal: overturning the perceived exceptionality of the Nazi era.

Memory and normalization

Overturning the sense of the past’s exceptionality is one of several goals that define the broader phenomenon of normalization. Normalization is a relatively new concept that historians and other scholars have increasingly employed to understand how and why perceptions of the past shift over time. The concept has been used in different ways: to explain how the past is represented in written history, how it takes shape in cultural memory, how it determines group identity, and even how it influences governmental policy. Regardless of the form it takes, normalization is defined by several basic features. At the most abstract level, it entails the replacement of difference with similarity. With respect to history and memory, for example, normalization involves a process through which a specific historical legacy comes to be viewed like any other.

The legacy may involve a particular era, an event, a person, or a combination thereof. But for a given past to become normalized, it has to shed the features that set it apart from other pasts. The normalization of the past can also shape the formation of group identity, enabling nations and other collectively defined groups to perceive themselves as being similar to, instead of different from, others. Normalization can furthermore liberate national governments to embrace the same kind of “normal” domestic and foreign policies that are pursued by other nations. To be sure, the assertion that normalizing the past can have these effects is underpinned by certain assumptions: first, that certain pasts may somehow be “abnormal” in the first place; second, that there is an ultimate end point of “normality” towards which all pasts eventually proceed. These assumptions are far from being unproblematic. But no matter what one thinks of them, they are rooted in an undeniable fact: not all pasts are created equal. Some are less – and some are more – “normal” than others.

Excerpted from Hi Hitler!: How the Nazi Past is Being Normalized in Contemporary Culture by Gavriel D. Rosenfeld. Copyright © 2015 by Gavriel D. Rosenfeld. Excerpted with permission by Cambridge University Press.