Tech

Hologram Daddies and Posthumous Molestation

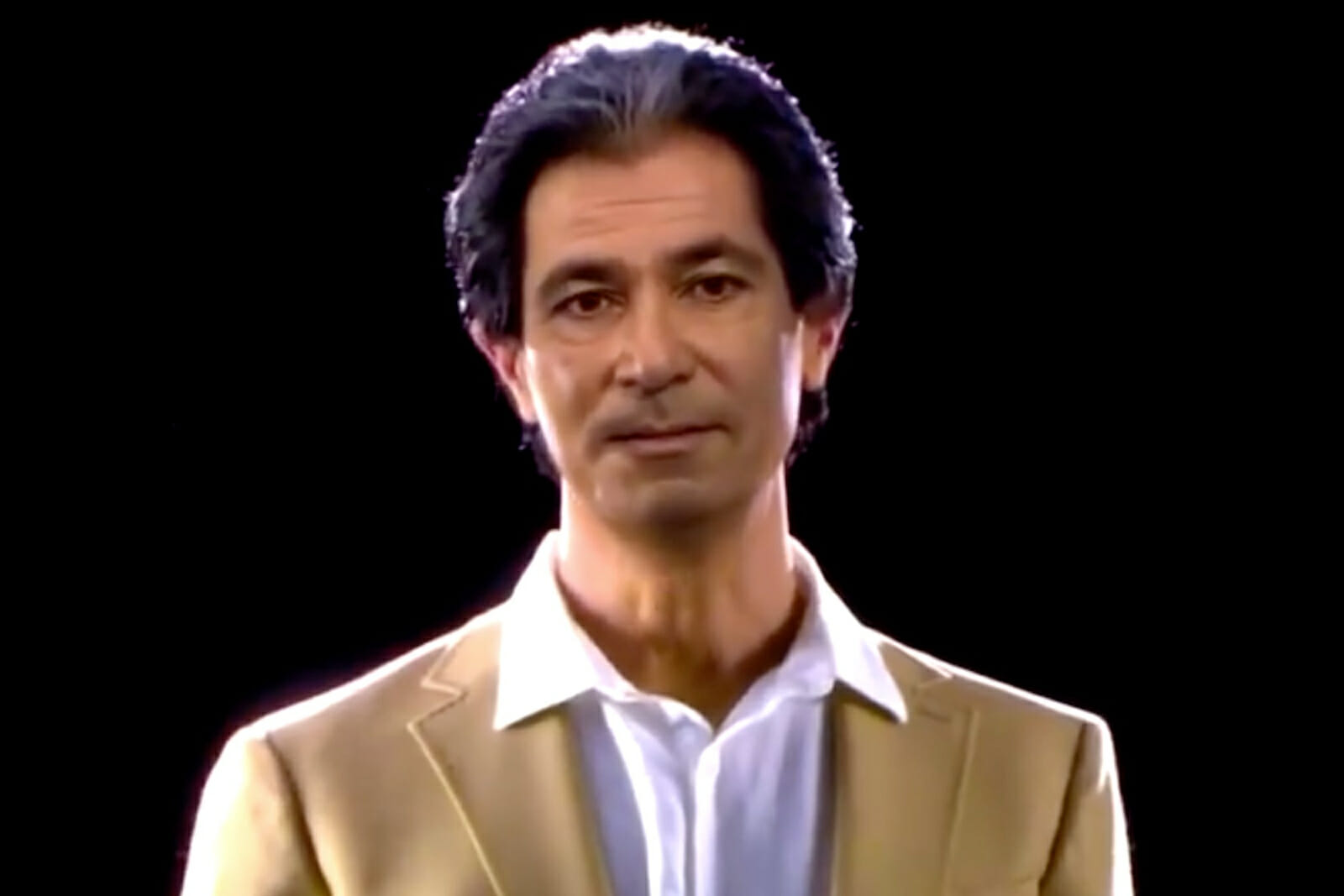

“I can’t even describe what this meant to me and my sisters, my brother, my mom and closest friends to experience together.” So remarked Kim Kardashian West with thanks and appreciation for a hologram of her father, Robert Kardashian, who died in 2003. The hologram of one of O.J. Simpson’s defence attorneys was a gift from husband and unsuccessful presidential aspirant Kanye West, a visually striking effort, yet implausible. The figure does speak of being “a proud Armenian father” but the factor of implausibility is enhanced by Kanye’s own scripting and contribution. With indulgence, the hologram tells Kim Kardashian in no uncertain terms that she “married the most, most, most, most, most, most genius man in the whole world, Kanye West.”

Human beings can find it hard to part with their dead. The departed and gathered are revisited, reconstituted, and even repurposed. In some particularly disturbing instances, their bodies are dug up again, subjected to trial, and punished. Oliver Cromwell, responsible for the execution of the Stuart king Charles I in 1649, was exhumed and posthumously executed, along with several regicides, in 1661. By then, the Sceptred Isle had been re-sceptred with the return of Charles I’s son. In monarchical restoration, revenge was sought by disgruntled royalists.

The famed diarist Samuel Pepys notes the wish to revisit these bodies of perpetration in an entry from December 4, 1660. “This day the Parliament voted that the bodies of Oliver, [Henry] Ireton, [John] Bradshaw, &c., should be taken up out of their graves in the [Westminster] Abbey, and drawn to the gallows, and there hanged and buried under it: which (methinks) do trouble me that a man of so great courage as he was, should have that dishonour, though otherwise he might deserve it enough.”

While Kanye West’s treatment of his spouse’s dead father is not quite in this league of extreme treatment, his efforts to hologram the dead did constitute a form of interference. It was certainly an appropriation. From the world of the deceased, these citizens are dredged up to serve roles for the living. Digital ethicist Per Axbom is particularly perturbed about the issue of rights and control in this process. “Even if a person gives their consent to being used as a hologram, is it even possible for this to be an informed consent?” To grant such consent might end up producing a hologram “expressing phrases or sentiments that are not part of their belief or value system.” The hologram as puppet; the real self potentially lost.

I can’t even describe what this meant to me and my sisters, my brother, my mom and closest friends to experience together. Thank you so much Kanye for this memory that will last a lifetime ✨ Here’s a more close up view to see the incredible detail. pic.twitter.com/XpxmuHRNok

— Kim Kardashian West (@KimKardashian) October 29, 2020

Kanye West’s holographic excursion was hardly the first. Resurrecting dead performers has become a feature of a music industry with an eye to continuing sales. Life may be short, but art is long and potentially profitable. In 2012, Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg entertained a crowd at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival with a resurrected Tupac Shakur. As Aaron Dodson described it, “A computer-generated Tupac made his proclamation to the crowd of 80,000. It raised his arms to roars before he began to perform his posthumous 1998 single ‘Hail Mary’ and the 1996 hit collaboration with Snoop, ‘2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted.’”

The late Whitney Houston has also come in for some posthumous molestation by death tech. In 2019, a deal was struck between the singer’s estate and music marketing company Primary Wave Publishing. The contents of the agreement included plans to produce a Broadway musical, release previously unheard tracks and run a Whitney Houston hologram tour. Pat Houston, the singer’s former manager, sister-in-law, and manager was adamant. “The hologram has taken over everything.” Salivating over prospective sales, she admitted that the estate “was looking to resuscitate her reputation.”

Despite being affected by cancellations due to the coronavirus pandemic, “An Evening with Whitney: The Whitney Houston Hologram Tour” did make a jerky start. “If you close your eyes it’s possible to bask in the voice and the unadulterated joy of ‘I Wanna Dance With Somebody’ and ‘How Will I Know,’” came the assessment from The Guardian after a February showing at the M&S Bank Arena in Liverpool. “But when you open them, it is deeply unsettling.” Unsettling, too, given how the lines “no matter what they take from me, they can’t take my dignity” jarring awkwardly, as the review claims, “with the sense of a ghoulish cash in.”

The ethical troubles of recreating such figures have not escaped the notice of those engaged in the process. An Amy Winehouse hologram tour was put on hold largely because of the suspicions of one of the actresses involved in its production. This was certainly not due to any concerns of Mitch Winehouse, who insisted the hologram project would render his late daughter more authentic. It was “a chance to show the real Amy, through hologram” and would portray her “at her best.”

According to the Los Angeles actress in question, left unnamed in GQ, she mistakenly assumed she was auditioning for a role in a biopic of the English singer. Auditions followed. No lines were given. Body measurements were taken; numerous photographs made. She was furnished with YouTube videos of live performances of Winehouse singing “Valerie” and “Rehab” with instructions to “replicate this performance and really hone in on Amy’s nuances.”

Suspicion was kindled. By the third audition, she asked one of the employees on whether it had anything to do with the Amy Winehouse tour. “He just shut it down and didn’t want to talk about it.” It was a revelation: she had been auditioning as Winehouse’s body double. Martin Tudor, an employee of the company behind the production, Base Hologram, explained the steps. “We start with a body double who works closely with our director to choreograph the performances and we take the results of that and go to work on it digitally.” As the actress observed, “Amy wasn’t treated like a human being when she was alive and this is treating her even more like a show pony.”

The dead are for the taking, at least in a digital sense. Companies are being founded to feed holographic demand. “Have you ever wished you had some tangible memory of a passed loved one? Yearned to see your parents or grandparents one more time?” So claims Artistry in Motion, with a promise to “offer high wealth clientele the opportunity to create lasting life legacies and powerful impressions.”

To such manipulations can be added the overall refurbishing of reality posed by the Deepfake phenomenon. Using Artificial Intelligence technology, the creator remains a controlling deity, doctoring the world, augmenting it, as it were, from news anchors to pornography. Neither the dead nor the living have been spared. There is money to be made and history to be revised.