Homicidal Drives: U.S. Dreams of Killing Putin

Wars disturb and delude. The Ukraine conflict is no exception. Misinformation is cantering through press accounts and media dispatches with feverish spread. Fear that a nuclear option might be deployed makes teeth chatter. And Russian President Vladimir Putin is being treated as a Botox Hitler-incarnate, a figure worthy of assassination.

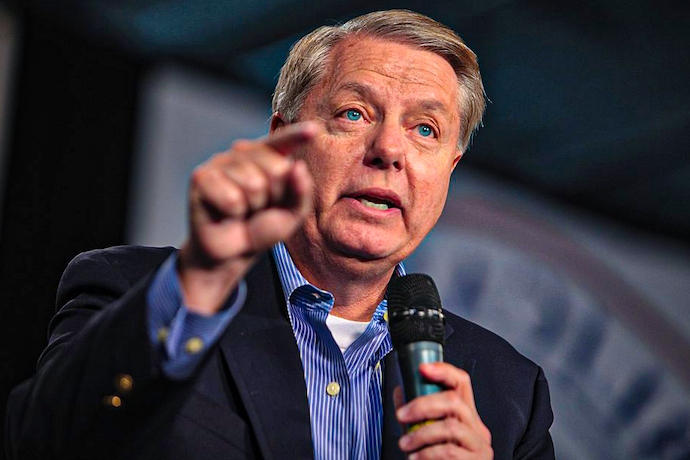

The idea of forcing Putin into the grave certainly tickled South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham. Liberated by more generous rules regarding hate speech (freedom in Silicon Valley is fickle), Graham took to Twitter to ask whether Russia had its own calculating Brutus willing to take the murderous initiative. Moving forward almost two millennia for a historical reference, the Senator pinched an example from the Second World War (when else?). “Is there a more successful Colonel Stauffenberg in the Russian military?” The only way to conclude the conflict was “for somebody in Russia to take this guy out.”

Is there a Brutus in Russia? Is there a more successful Colonel Stauffenberg in the Russian military?

The only way this ends is for somebody in Russia to take this guy out.

You would be doing your country – and the world – a great service.

— Lindsey Graham (@LindseyGrahamSC) March 4, 2022

In support of the proposition came Fox News host Sean Hannity, using long-discredited logic in dealing with the leaders of a country. “You cut off the head of the snake and you kill the snake. Right now, the snake is Vladimir Putin.”

Armchair psychologist types tend to suggest that homicidal fantasies are fairly common. Julia Shaw of University College London told those attending the Cheltenham Science Festival in 2019 that this was to be expected from humans, enabling them to think through “the consequences” of their actions, obey a moral code and “develop our empathy.”

Shaw might have missed a beat on this one, especially regarding the harm wished upon the Russian leader from a certain number in self-declared Freedom’s Land. Empathy has been in short supply, and the moral code, if it can be called that, has gone begging.

Graham’s homicidal call did bring out its critics, but the outrage was far from unconditional. To have shown balance would have betrayed the cause and revealed solidarity for wickedness. There were the mild, spanking rebukes from Democrat Congresswoman Ilhan Omar from Minnesota. “As the world pays attention to how the U.S. and its leaders are responding, Lindsey’s remarks and remarks made by some House members aren’t helpful.”

Republican Senator Ted Cruz thought it “an exceptionally bad idea,” preferring “massive economic sanctions,” boycotts of Russian oil and gas, and the provision of military aid to Ukraine. Democratic Hawaii Senator Brian Schatz, Chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, wondered if a certain number of people had lost their minds. “I have seen at least a half a dozen insane tweets tonight. Please everyone keep your wits about you.”

Billionaire financier Bill Browder, the inspiration behind the Magnitsky Act of 2012, preferred to diminish Putin as “a very little man. He’s very scared of everybody, and he’s very vindictive. And so he’s constantly looking around for betrayal.” Hardly worth assassinating, it would seem.

One should give Graham some leeway here, despite the flat assertion by White House press secretary Jen Psaki that assassination was “not the policy of the United States.” Given that the U.S. has not been averse to assassinating leaders or prominent figures, why be squeamish now? President Abraham Lincoln thought it morally appropriate to condone the assassination of leaders who had caused suffering for an extended period of time, and could not be ousted by peaceful or legal means. With Cleo’s irony, he would himself be assassinated along the lines of such logic by thespian John Wilkes Booth.

For decades, Washington wished to do away with Cuba’s obstinately resilient Fidel Castro, bumbling along and eventually failing. (Such oafish, nursery incompetence surely demands a Netflix production.)

With the People’s Republic of China starting to make its mark in the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower thought it appropriate that a blow be struck by singling out one of the Communist state’s brighter lights, Premier Zhou Enlai. The Central Intelligence Agency’s murderous effort involved blowing up an Air India flight for Bandung in 1955, killing 16 passengers. Zhou never boarded the flight. A second effort at attempted poisoning was aborted.

The CIA did not always fail, even if it gave an excellent impression of doing so. There was more success in operations against Congo’s Patrice Lumumba and the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo.

During the absurdly named “Global War On Terror,” drones became the weapon of choice to target high-profile figures, a murderous policy given a bubble wrapping of weasel words. As recently as January 2020, President Donald Trump went so far as to order the killing of one of Iran’s most popular figures, the legendary leader of the Quds Force, Qassem Soleimani.

At stages, U.S. officials have shown remarkable candour on the policy of targeting heads of state, despite the existence of Executive Order 12333 which states that, “No person employed by or acting on behalf of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in, assassination.”

In 1990, Air Force Chief of Staff General Michael Dugan promised that, in the event of war between the two countries, U.S. planes would make a special point of targeting Saddam Hussein, his family, and his mistress. It must have then come as a surprise to him that a certain Secretary of Defense, the usually amoral Dick Cheney, would sack him for making comments possibly in violation of the assassination ban. Dugan should have stuck to generalities, such as targeting the country’s leadership. It’s all in the presentation.

What of the point of assassination, that most severe form of censorship? Stephen Kinzer is solid in pointing out that liquidating that man in the Kremlin will hardly guarantee a more accommodating replacement. “No one who hopes to secure power in Moscow…could ever accept Ukraine’s entry into NATO or the presence of hostile troops on Ukrainian soil.” But Kinzer is even more on the mark for pointing out that U.S. efforts tend to be hallmarks of stunning failure.

All this chatter about purported tyrannicide should not detract from the pattern of U.S. history, which has affirmed that the imperium will dispose of leaders and prominent figures it does not like, even if it fails along the way. Little wonder that Graham and his ilk are urging Russians to fulfill their blood-soaked fantasies.