Hostages to Fortune as Law is Held to Ransom

There are times it is obvious the world has changed. Dallas 1963, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Brexit. There are times when it is not immediately obvious. Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s driver taking a wrong turn in Sarajevo in June 1914. It is the consequences that make us realize how important the initial moment was. One such moment was last week.

It was not the arrest, on a U.S. request in Canada over alleged breaches of Iranian sanctions, of the Huawei chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou that was so significant. Nor her bail. What changed the world was the admission by the U.S. president that she was a hostage to fortune. Trump achieved something incredible, judicial equivocacy with China.

China retaliated by arresting two Canadians, not confirming exactly why except using the catch-all phrase involving “national security.”

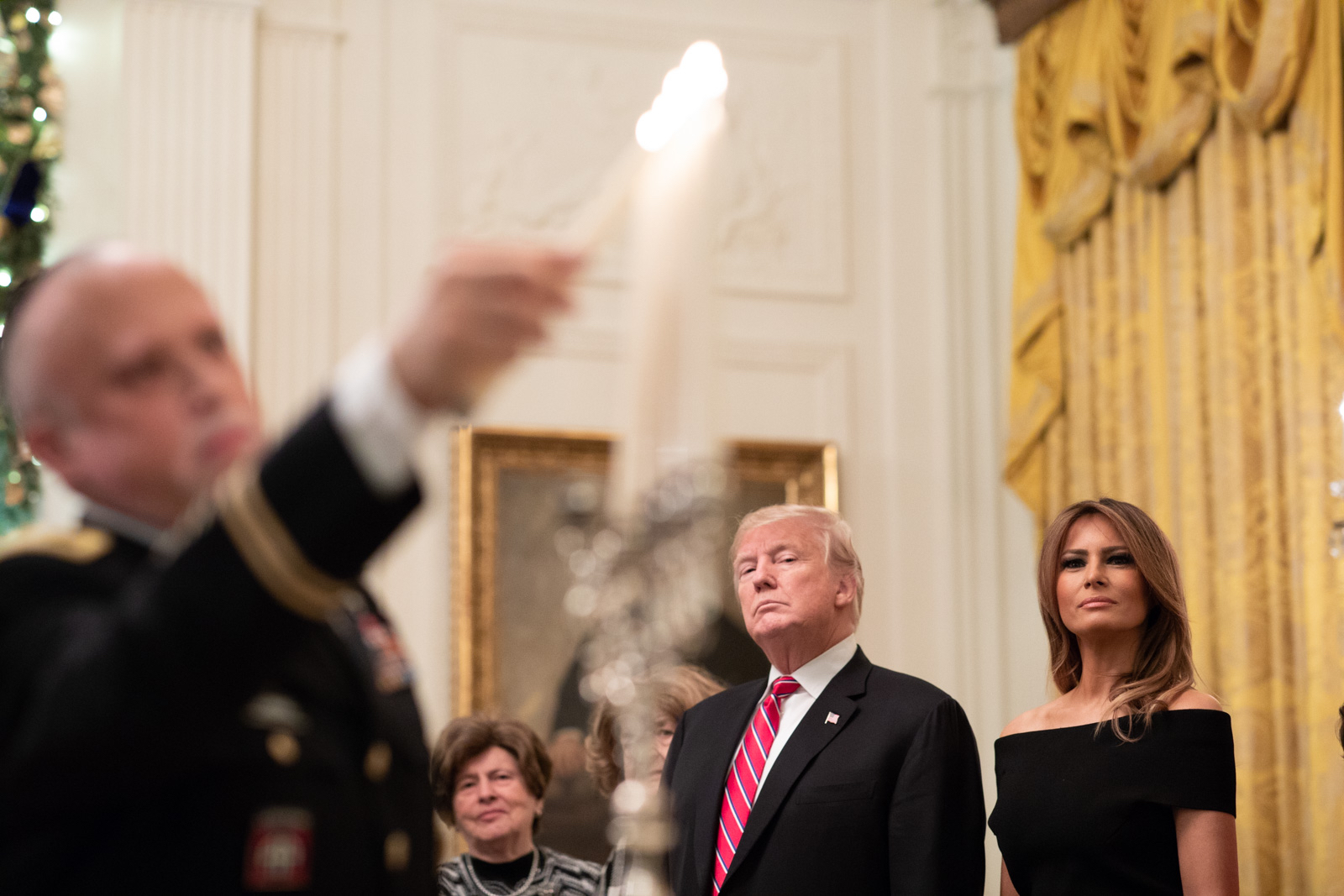

U.S. President Donald Trump said that he could use his power as president to intervene in the case of Meng. Intervention, he added, might help serve the interest of U.S. national security or enhance the prospects of a trade deal with China.

“If I think it’s good for the country, if I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made – which is a very important thing – what’s good for national security, I would certainly intervene if I thought it was necessary,” he said. Presidential interference has sent the wrong message though one they would understand in China; subordinating due process.

Beijing saw Meng’s arrest as a flagrant abuse of such a process. Detaining an individual to be used as a pawn on trade deals leaves the world a more dangerous and unpredictable place. The art of the deal? What deal worth its salt could emerge by holding someone hostage as a trade negotiation ploy.

Meng’s seizure, and the retaliatory arrest of Canadians in China, has everything to do with U.S.-China economic rivalry and precious little to do with international law. Trump’s intervention, rebuked by the U.S. Department of Justice, cast an unfavorable light on the U.S. legal system and made it look no more just than Beijing’s. The Justice Department’s top national security official last week insisted his prosecutors will not be influenced by what the White House does. “We are not a tool of trade when we bring the cases,” Assistant Attorney General John Demers told a Senate panel.

“What we do at the Justice Department is law enforcement. We don’t do trade,” he added. But a trade-off is exactly how it looks in Beijing.

Both sides appear guilty of what amounts, in effect, to hostage-taking. Breaching Iran sanctions, imposed by the U.S., is what Meng is being held for but the background is pertinent. Huawei is the world’s largest supplier of telecommunications network equipment and second-biggest maker of smartphones. It is considered an agent of the Chinese state. But is the U.S. blameless in this regard? “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist.” So warned Eisenhower just before leaving the White House in January 1961.

Hostage taking seems to be an intricate part in the art of the deal.

The archduke’s car has just taken a wrong turn. We await the consequences.