How a Peanut Farmer from Georgia Made Human Rights Matter

“Human rights is the soul of our foreign policy. And I say this with assurance, because human rights is the soul of our sense of nationhood.” – Jimmy Carter, December 6, 1978

Jimmy Carter holds a place in the public imagination as America’s “human rights president” because he pursued a high-profile policy and continued his activism in a remarkably ambitious post-presidency. Depending on one’s political stance—and perhaps one’s moral compass—human rights may rank among Carter’s greatest achievements or his most notable failures. Contemporary critics called his efforts naïve, quixotic, inimical to broader national interests, and even dangerous, while his supporters credited him with reviving the nation’s democratic reputation by moving the United States beyond realpolitik and parochial anti-communism.

In reality, Carter’s human rights policy was not as inept or as risky as his detractors maintained, nor was it as groundbreaking as his supporters insisted, and even his successes paid him few political dividends. Yet in building on a movement that predated his presidency, he governed by a different standard than his predecessors, and by the end of his presidency in 1981, he could list many genuine accomplishments.

The dilemmas of activism

Carter’s embrace of human rights reflected both his personal principles and his political acumen. Sensing the popular demand for a new brand of politics in the post-Watergate era, he took up human rights as an oppositional campaign strategy. He hoped that a robust policy would transcend the narrow paternalism of Cold War anti-communism and restore America’s reputation as the world’s foremost champion of liberal democracy. “We’ve been through some sordid and embarrassing years recently with Vietnam and Cambodia and Watergate and the CIA revelations,” he explained early in his presidency, “and I felt like it was time for our country to hold a beacon light of something pure and decent and right and proper that would rally our citizens to a cause.”

He was active from the very first days of his presidency. He spoke out for dissidents, cut military aid to some governments, and privately broached human rights with others—often inciting harsh responses in the process. When he asserted in his opening letter to Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev that “we cannot be indifferent to the fate of freedom and individual human rights,” Brezhnev clarified that Moscow would not accept interference in its internal affairs regarding “the so-called question of human rights…whatever pseudo-humanitarian slogans are used to present it.” In time, the Carter administration developed a wide array of tools to intercede with foreign governments, from the carrot of positive inducements to the stick of economic sanctions.

This activism put him in a bind. Because an American president has a primary responsibility to maintain key security and trade relationships, he could not easily disregard American ties to undemocratic regimes of the right or left. Conservatives accused him of ignoring communist governments, liberals accused him of overlooking rightist dictators, and activists complained he was doing too little altogether. Realists called his policy moralistic and confusing, while others bemoaned his diplomatic inexperience.

Some charged him with inconsistency. He focused much of his attention on the socialist states of Eastern Europe and the military governments of South America, but he had much less to say about abuses in East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. These regional priorities led one critic to assert that he was dividing the world into two categories: “countries unimportant enough to be hectored about human rights and countries important enough to get away with murder.” Of the nearly seventy states that were potential recipients of American weapons or security assistance, aid was ultimately reduced or terminated to only eight Latin American nations.

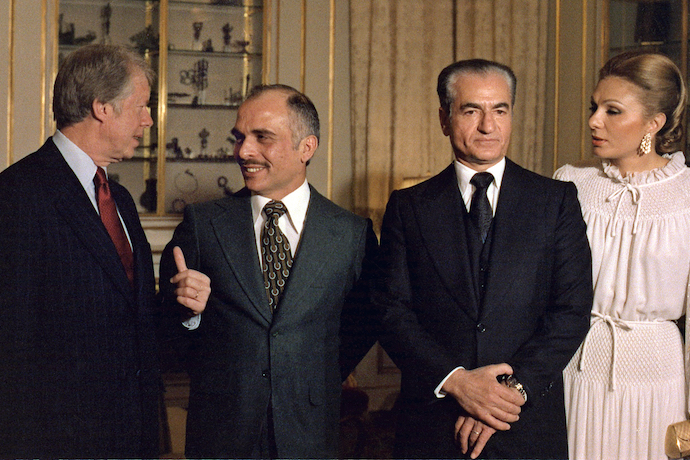

His public diplomacy added fuel to the critics’ fire. When he welcomed the Romanian and Yugoslavian dictators Nicolae Ceaușescu and Josip Broz Tito to Washington, he was continuing the longstanding U.S. policy of pulling communist states away from Moscow. Yet these men were autocrats who granted their citizens few liberties. When he met with several Latin American dictators, activists were livid that Carter was engaging with, as one put it, “the most motley collection of butchers ever assembled.”

Carter never abandoned his human rights policy altogether, but with the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, he shed the vagaries of moral appeals in favor of the pre-Vietnam War certainties of overt anti-communism.

The Carter legacy

With the benefit of hindsight, human rights advocates find much to admire in Jimmy Carter’s record. He took a fledgling movement and helped to institutionalize it both domestically and internationally. His presidency lent more visibility to global human rights, bolstered America’s democratic reputation for a time, and even boosted the morale of the persecuted. When the Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov was asked in 1977 if Carter’s activism had led Moscow to crack down on dissenters, he answered, “Categorically, no! Repressions are our daily life.”

Carter accomplished a great deal in South America. Disappearances in Argentina and torture in Uruguay and Paraguay declined through a combination of those nations’ changing domestic situations, increased international attention, and U.S. incentives. The Argentine journalist Jacobo Timerman, who was released from prison through outside intervention, asserted that America’s human rights efforts had a value that outweighed their inherent limitations: “What a human rights foreign policy does is save lives. And Jimmy Carter’s policy did.”

The Carter administration’s human rights policy also had considerable weaknesses. It could not overcome the perception of its internal contradictions or the impossibility of even-handedness. Carter often wavered when dealing with undemocratic regimes, and this combination of sanctions and support usually hurt relations while not necessarily reducing violations. During Argentina’s “Dirty War,” his administration allowed the Argentine junta to buy an unprecedented amount of military hardware before finally terminating arms sales, and afterward, the generals simply purchased from other countries. Meanwhile, concrete successes in the USSR—freed political prisoners and increased emigration numbers—were the work of painstaking private diplomacy and might have been achieved without the accusatory public rhetoric.

Still, it is hard to deny that Carter’s policies influenced global events. In the short term, he showed the world that mere anti-communism was not enough to ensure American support. This turnabout helped convince some governments to adjust their practices. Despite some activists’ disappointment, those who understood the complexities of the policymaking process were more forgiving. In the words of Amnesty International USA director David Hawk, “Anyone who worked in the field of human rights before Carter became president can appreciate the difference he makes.”

In the long term, we must credit Carter with giving a shot in the arm to the dissident cause in Eastern Europe and further developing the language and the tools with which his successors could challenge these repressive governments in the 1980s. Carter also arguably contributed to the democratization trend that swept the globe in the late 1970s and 1980s—a period in which democratically elected governments replaced undemocratic ones in dozens of nations worldwide. In the final analysis, whatever weaknesses Jimmy Carter had as president, he did as much as any major political actor in the world to further the cause of international human rights.