How to Understand China’s Post-Cold War Ascent

It is impossible to fathom that the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union were once bitter adversaries during the Cold War. Since 1991, the Russian Federation, the Soviet Union’s legal heir and political successor, has cultivated a powerful alliance with today’s China. The Chinese-Russian relationship has served as a powerful counterweight to the United States, specifically in the global economic, security, and political arenas. China has benefitted from this “no limits” partnership to achieve its rising dominance on the world stage.

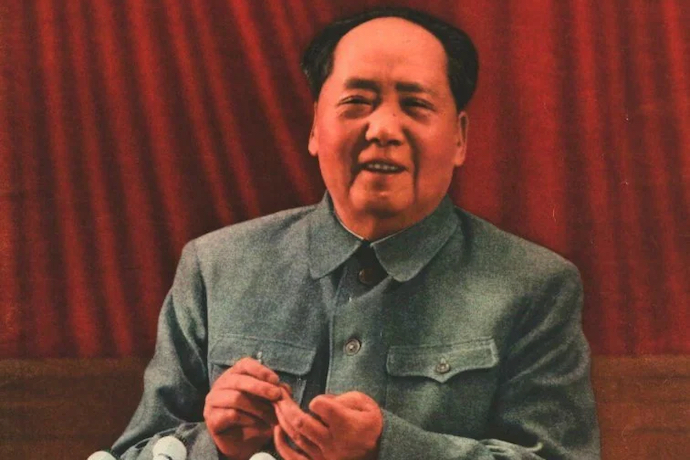

Historically, Soviet-Chinese ties were toxic since 1949. The debate over who would be the standard-bearer of international communist policies was never settled, and because of this friction, the Soviets and Chinese suffered from their own cold war. Mao and Stalin competed over helping communist forces during the Korean War in addition to leading fledgling countries that had Marxist leanings. The Soviets and the Chinese frequently collaborated on blocking resolutions at the UN Security Council, but any illusion of unity between the two leading communist countries was fleeting. Longstanding border disputes resulted in territorial skirmishes that eventually were recognized as an ongoing war in 1969. The border conflict was only a symptom of a relationship that was fraught with peril.

President Richard Nixon sought détente with the Soviet Union and China for the specific purpose of normalizing relations to conveniently balance them off one another. Nixon understood the counterweight both countries served and used this adversarial relationship between the two leading communist countries to achieve equilibrium in global affairs. The balance of power swung to the West during the 1970s when China and the Soviet Union were locked in triangular cohesion on the world stage with the United States. China was now competing with the Soviet Union for cooperative defense and diplomacy with its other adversary, the United States.

The three adversaries were locked into a triangular stalemate, which eliminated the likelihood of two of the three being able to counter the third. Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s global structural engineering is a prodigious example of statesmanship at its finest. Like Richelieu who exploited divisions in the Balkans for the benefit of the House of Bourbon in France against the Habsburg monarchy in Austria-Hungary and Spain, Nixon and Kissinger engineered a new world order based on triangular parity by recognizing that the world’s two most powerful communist countries were desperately seeking leverage against one another.

Secretary of State George Shultz in his memoirs stated how the Chinese diplomats he dealt with were consumed by a Confucian mindset and staunch ethnocentrism. The Chinese were focused on their goals of strengthening their security against the massive Soviet military buildup on their border. The main point of contention by the Chinese during the 1980s was that the Soviet leadership pursued policies of aggressive military and nuclear posturing aimed at China. The balance of power in the Chinese-Soviet militarized border zone foreboded a bleak future of continued competition with strategic nuclear missiles pointed at one another.

China’s strategic posturing was enhanced by the actions of reformer Mikhail Gorbachev, who implemented Perestroika and Glasnost to remake the Soviet Union based on principles of democratic socialism as opposed to communism. This paved the way for a decentralized Soviet Union and dovish foreign and defense policies, which is the reason why a brief coup attempt occurred by hardline elements within the Kremlin when Gorbachev was at his dacha during the summer of 1991. The Soviet Union disintegrated, and the most important consequence in the international community was that the Soviet Union and China would no longer be locked in a constant state of military and political gridlock. China was freer to pursue its defense goals and its primary objective of becoming a regional hegemonic power with global ambitions circulating in debates within and between the various wings of China’s one-party system.

China’s ethnocentrism has been a guiding ideology in its global outlook. Sinocentrism has been a characteristic that has pervaded throughout the various dynasties in the Chinese territories. When former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who served under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, visited Vietnam decades after being considered the architect of the Vietnam War, he was told by Vietnamese officials that the Americans completely misunderstood China’s relationship with Asian countries. Namely, Vietnam had been fighting against the Chinese for centuries during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

According to McNamara, Vietcong leaders were in complete agreement that Vietnam must actively curb China’s regional hegemonic ambitions. McNamara was in complete shock because of his American Cold War mindset that dictated the possibility that every Asian communist country would likely become “a pawn of the Chinese.” This ambition to become a regional hegemonic power was within China’s grasp because of the dissolution of the Soviet military threat and had been a centuries-old fixation of the “Middle Kingdom” because of its inherent ethnocentrism.

The Chinese began pursuing aggressive and domineering policies toward both nearby countries and maritime domains after the fall of the Soviet Union. The 1990s brought a renewed vigor to Beijing that propelled it to take the lead in ensuring security in the South China Sea, as well as asserting sole arbitration of all maritime activities. China has pursued these regional hegemonic policies in the South China Sea with the aim of maintaining its trade route, acquiring minerals and resources, and preventing the United States from furthering its missile defense capabilities in the region.

During the Obama years, the foreign policy establishment advocated a pivot from the Middle East to Asia with the intention of competing with an emboldened China. American missile defense capabilities in the region have increased dramatically. For example, the United States contributed to Seoul’s defense capabilities by providing it with anti-ballistic missile defense systems to the chagrin of both China and Russia, which has become China’s stalwart ally on all matters pertaining to China’s claims in the South China Sea.

As Professor Graham Allison shrewdly pointed to the contradiction of American intransigence to allowing China to assert its regional hegemony, he explained that the United States has a Monroe Doctrine. Therefore, why is China not entitled to exercise control within its regional parameters? The Monroe Doctrine extends to both North America and South America. Ronald Reagan sent the U.S. military to liberate Grenada after a coup in 1982 without any regard for Grenadian sovereignty, and Bill Clinton sent the U.S. military to depose the Haitian regime that illegally ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1994.

The United States reserves the right to act as a policing mechanism in the Western hemisphere. The question for foreign policymakers is whether China has the right to impose regional control in its maritime sphere, while the United States enjoys this privilege in its own hemisphere. The West further intervened in the Asia-Pacific by creating the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which was proposed by the United States to ensure China cannot exercise full control over maritime activities in the South China Sea or anywhere in the region.

Turning westward, China has had a contentious relationship with India, and this has kept China’s ambitions in South Asia in complete gridlock. India and China, two of the most powerful BRICS countries, retain a plethora of conflicts in virtually every area of global and regional governance. China has sought to counter India’s rising position on the world stage by persistently blocking any attempt to enable New Delhi to attain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. In addition to this, China is hesitant to embolden Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who pursues policies through the prism of his Hindu nationalist political orientation that China believes may destabilize South Asia and adversely affect East Asia.

China has also further undermined India by supporting Pakistan militarily and diplomatically. China has bolstered Pakistan magnanimously since 2011 when Osama bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad. Pakistan’s economy was in dire straits until the United States began providing financial support in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The United States was Pakistan’s main benefactor and provided counterterrorism assistance from 2001 to 2011.

Bin Laden’s death sent shockwaves through the American foreign policy establishment because the Al Qaeda leader was hiding in Abbottabad with the probable knowledge of the Pakistani military and ISI intelligence apparatus. American aid to Pakistan now took a different path, and China has been Pakistan’s primary benefactor, which is the reason why Pakistan’s economy has not collapsed. Chinese investments in Pakistan’s private sector, infrastructure, and trade opportunities have propped up its economy.

Furthermore, China has been a longstanding instigator of the conflict in Kashmir by supporting Pakistan’s claim to Kashmiri territories and even claiming the Kashmiri territory of Aksai Chin belongs to China, not India. China has challenged India’s territorial integrity and aided Pakistan’s constant war-like competition against India to maintain its role as the most powerful Asian country militarily and economically.

During the 1990s, the Clinton administration sought to normalize relations with China and support entry for China into the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and global markets. This has propelled China’s climb in the global economy. The Clinton administration debated whether to link Chinese entry into the global financial framework to human rights and its treatment of ethnic minorities within mainland China.

This was opposed by Professor John Mearsheimer, who is a proponent of Offensive Realism and advocates power maximization and not emboldening others at the expense of your own country. Mearsheimer vigorously opposed enabling China’s free entry into global financial markets with little in return except for goodwill assurances and diplomatic pleasantries. Mearsheimer points to the toxic U.S.-China relations as evidence of this ill-advised policy.

While the Chinese economy began its meteoric rise in the 1990s, the Russian economy spiraled into a monstrous downturn. The Russian economy had been misguided, mismanaged, and corrupted by the state of instability that characterized the presidency of Boris Yeltsin, who suffered from debilitating health problems and retained a corrupt circle of bureaucrats. The Kremlin never received the financial support it requested from the United States and suffered from foreign policy embarrassments resulting from the Partnership for Peace in which Russia’s junior partner status developed into an unmitigated disaster for Russia’s standing in world affairs.

The Chinese sensed an opportunity and began a new path to prosperous relations with Russia with its goal to rise to global preeminence. The Russians were now in a partnership with China, and they were no longer at the mercy of their American counterparts. Russia’s importance placed on its relationship with China can be best demonstrated by President Vladimir Putin claiming that solving the border conflict with China was one of his most important foreign policy achievements. Vitaly Churkin, the late Russian ambassador to the United Nations, always described Russian relations with China as “excellent.” China’s former adversary was now its closest ally, and this shifted the world order and continues to pose challenges to America’s preeminence.

China and Russia are shifting the world order when acting in concert on virtually every issue, including Ukraine, Taiwan, and North Korea. The 1990s heralded a powerful new competitor in the global markets, and the last decade has seen China implement its Belt and Road Initiative in which more than 150 countries have received Chinese financial support for investment, trade, and infrastructure in exchange for diplomatic and defense support. The Chinese ascent began with its adversary the Soviet Union disintegrating in 1991 and led it to become more militarily, diplomatically, and economically powerful. China’s ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’ in which Beijing aggressively pursues its policies with the mindset of an imminent superpower in the global diplomatic, defense, and economic realms is progressing at an alarming speed.

Henry Kissinger recently said with regard to U.S.-China relations: “We’re in the classic pre-World War One situation, where neither side has much margin of political concession and in which any disturbance of the equilibrium can lead to catastrophic consequences.” With the Soviet Union transforming from being China’s enemy to Russia becoming China’s stalwart ally, a chain of events catalyzed seismic changes to the world order. China’s global financial and military clout grew exponentially after the fall of the Soviet Union, which resulted in more assertive posturing in regional and global affairs.

The future remains a perplexing question as to whether a Thucydides Trap in which a rising power and established superpower clash militarily as a result of fear, misperception, or a confluence of factors. If this trap is avoided between the United States and China, then the road to cooperation and diplomacy will prevail in which these two countries decide a dual enterprise moving forward will save lives, avoid conflict, and bring prosperity to the international community. The future will depend on which path is taken.