Politics

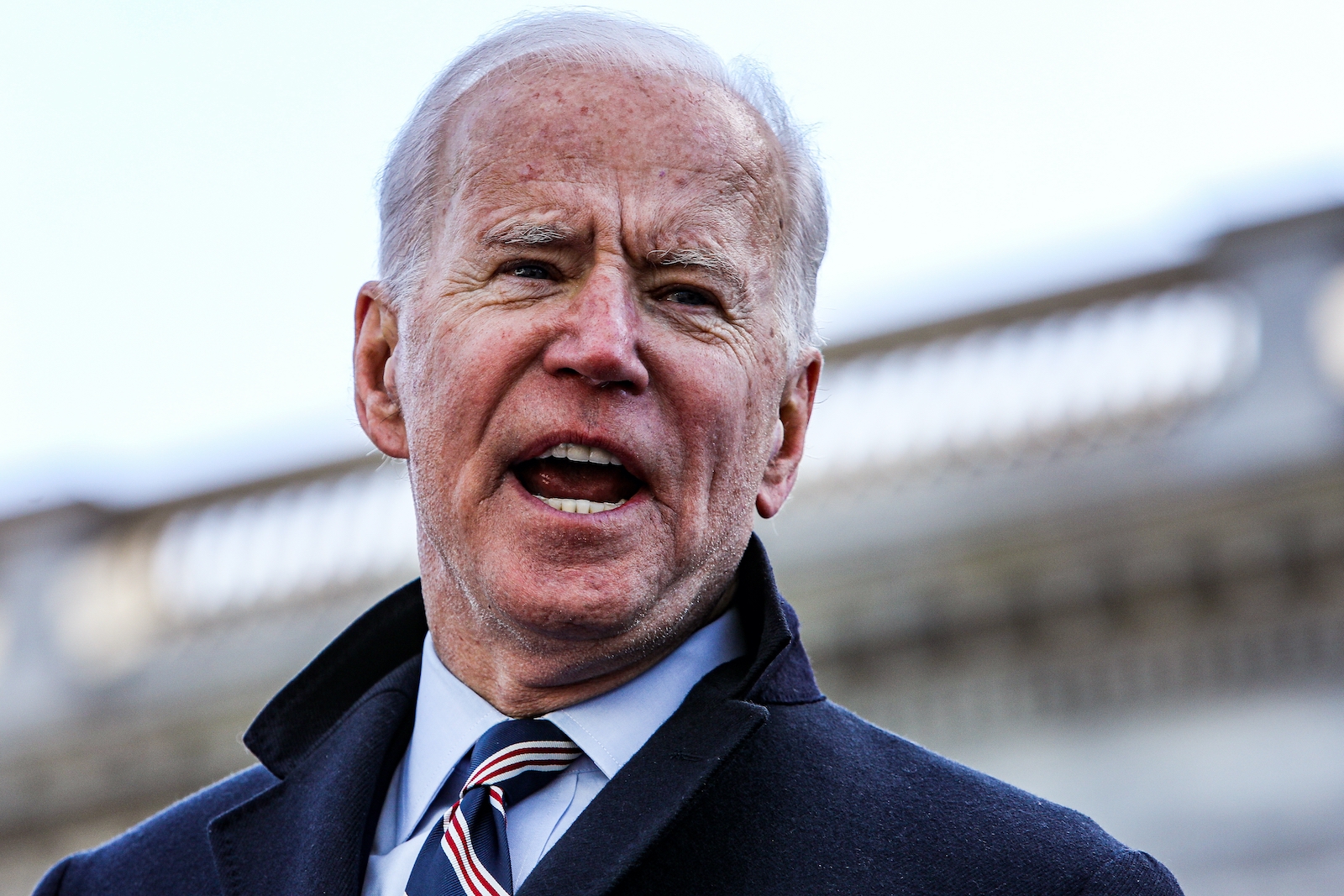

In Search of Shallow Doctrines: Joe Biden and Trumpism Shorn

The US presidential doctrine is an odd creature. Usually summoned up by security wonks and satellite personnel who revolve around the president, these eventually assume the name of the person holding office. They are given the force of a Papal bull and treated by the priest pundits as binding, coherent, and sound.

Much of this is often simple mythmaking for the imperial minder in the White House, betraying what are often shallow understandings about global politics and movements. Clarity and details are often found wanting. Variety in such doctrinal matters, the Soviet Union’s veteran diplomat Andrei Gromyko noted in casting his eye over the US approach, meant that there was no “solid, coherent and consistent policy” in the field.

In the case of President Joe Biden, any doctrine was bound to be a readjustment made in hostility to the Trump administration, at least superficially. But in so many ways, Biden has simply pulled down the blinds and kept the US policy train going, notably in its approach to China and its unabashed embrace of the Anglosphere. There remain smatterings of nativism, doses of protectionism. There is the childlike evangelism that insists on enlightened democracy doing battle with vicious autocracy. This was, according to Foreign Affairs, the “everything doctrine.”

Such an approach would barely astonish. Robert Gates, former US Defense Secretary, did claim in his memoir with sharp certitude that the current president’s record, prior to coming to office, was patchy, proving to be “wrong on nearly every foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades.”

At the time, a stung White House demurred from the view through remarks made by National Security Council spokesperson Caitlin Hayden. “The President [Barack Obama] disagrees with Secretary Gates’ assessment – from his leadership on the Balkans in the Senate, to his efforts to end the war in Iraq, Joe Biden has been one of the leading statesmen of his time, and has helped advance America’s leadership in the world.”

Anne-Marie Slaughter, writing mid-November last year, suggested that the world was finally getting a sense of “the contours of” Biden’s foreign policy, which was a veritable shop of goodies. “He has,” she claimed in reproach, much along the line taken in Foreign Affairs, “something for everyone.” For the China bashers, he has pushed “the Quad” of India, Australia, Japan, and the United States and created AUKUS, “a new British, Australian, US nexus with the…submarine deal, no matter how clumsily handled.”

A throbbing human rights narrative has also taken some shape, an approach neither convincing nor commanding. Again, China features as the main target, being accused of genocide and grave human rights abuses, though Beijing can be assured that the sword of US military power will be, at least for the moment, sheathed from attempts to protect them. What remains less certain is whether the same thing can be said about Taiwan.

The liberal internationalists can cheer the boosting rhetoric of international institutions: the gleeful nod towards the World Health Organization, the recommitment of the US to pursuing goals to alleviate the problems of climate change; the revitalisation of NATO, an alliance derided by former President Donald Trump.

From Chatham House, we see the view that Biden’s “pragmatic realism,” which eschews sentimentalism to traditional allies while still respecting them, took the Europeans “off-guard” with Washington’s energetic focus on the Indo-Pacific.

Slaughter has charged that, if all are recipients of something, a doctrine remains hard to “pin down.” She remains unconvinced by the stacked pantry, wishing to see a more concerted effort that embraces “thinking that shifts away from states, whether great powers or lesser powers, democracies or autocracies.” Embrace, she commands, “globalism,” with an emphasis on cooperation irrespective of political or ideological stripes. “From a people-first perspective, saving the planet for humanity must be a goal that takes precedence over all others.”

This view is far from spanking in its novelty. With every change of the guard in Washington, opinions such as those of Slaughter become resurgent, often messianic urgings that claim to make things anew and see the world afresh. In her case, there is a recycled One World quality to it, with the US, of course, as central leader. Bill Clinton, as a presidential candidate in 1992, insisted that it was “time to put people first.” In accepting the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 1996, he spoke of building “that bridge to the 21st century, to meet our challenges and protect our values.”

How fine a vision that turned out to be, with the US ensuring its position as the sole superpower, with an amassed military able to strike, globally, any part of the planet with impunity and, as Clinton himself showed, frivolous, criminal distraction. Washington continued to bribe and coddle satraps and client states, seeking janitors to mind the imperium and keep any power that might dare to challenge the status quo in stern, severe check. Little wonder, then, that Beijing threatens such self-serving understanding.

The transcendent, humanity-driven view will not sit well in the Bidenverse, which remains moored in a brand of power politics that is Trumpism shorn, with a range of other antecedents. The “America First” ideals of the previous president have been retained, though the howling about the risks of a complex world has simply been delivered in another register. The open question, and one yielding a potentially troubling answer, is how far US military power will be used to shore up a shoddy, shallow doctrine that shows all the signs of the old.