India v. China: It’s a Mexican Standoff

India is now the belle of the ball, as most of the world and Asian regional powers make pilgrimages to New Delhi to flatter and flirt with India’s dynamic Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. Modi and India come with a certain amount of unpleasant baggage, which its suitors do their best to ignore. Modi himself is an unrepentant Hindutva cultural chauvinist whose attitudes toward Muslims (and convincing circumstantial evidence of his involvement in an anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat—so convincing, in fact, he was previously banned from the United States) trend toward the fascistic.

In regional affairs, India has not been a particularly responsible or constructive actor, having mixed it up with Pakistan (abetted the split-off of East Pakistan a.ka. Bangladesh), Nepal (opened the door to the Nepalese Communists with its inept deposition of the King), and Sikkim (Sikkim, in case you noticed, doesn’t exist anymore; it was annexed by India in 1975) and presided over a bloody insurgency and brutal counterinsurgency in Kashmir that has claimed the lives of at least 60,000 people. India birthed the horrific Tamil Tiger insurgency in Sri Lanka and its intelligence services played what may have been a decisive role in organizing and executing the successful electoral challenge on January 8, 2015,to the rule of the pro-Chinese (now-ex) president of Sri Lanka, Mahinda Rajapaksa.

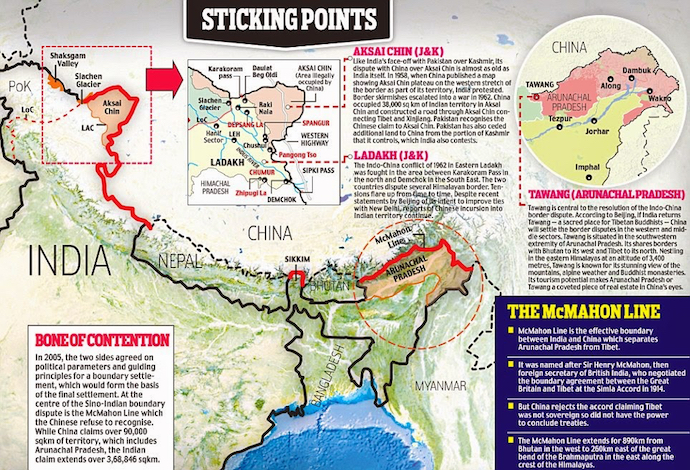

And there’s the People’s Republic of China, and the contested issue of the borderlands of Arunachal Pradesh in the northeast and Aksai Chin in the northwest. Japan’s Foreign Minister, Fumio Kishida, got himself tangled up in the Arunachal Pradesh issue during his recent visit to India.

China today lodged a protest with Tokyo after Japan’s foreign minister was quoted as saying that Arunachal Pradesh was “India’s territory.” Japan’s Sankei Shimbun, a conservative daily, quoted Fumio Kishida as having made the remarks in New Delhi on Saturday. Japan played down the issue today, saying it could not confirm Kishida’s reported remarks. It added that it hoped India and China could resolve their border dispute peacefully. Kishida’s reported remarks drew an angry response from China, which called on Tokyo to “understand the sensitivity of the Sino-India boundary issue.”

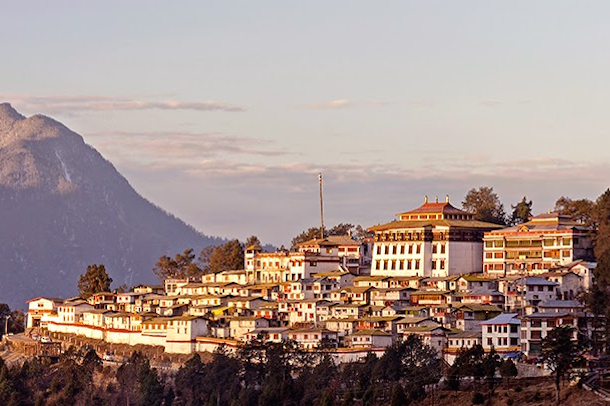

A Japanese foreign ministry spokesperson said “the statement was made considering the reality that Arunachal Pradesh state is basically in reality controlled by India and that China and India are continuing negotiations over the border dispute.” China disputes the entire territory of Arunachal, calling it south Tibet, especially Tawang, a key site for Tibetan Buddhism. The historic town briefly fell into Chinese hands during their 1962 war before Beijing retreated.

The Japanese Foreign Ministry backtracked expeditiously, indicating that Kishida’s remarks were perhaps a slip of the tongue and not meant to inject Japan into the Arunachal Pradesh issue. Ever since Prime Minister Abe returned to office with an India-centric Asian policy, yearnings have been expressed that Japan might openly side with India on the Arunachal Pradesh issue. The PRC, was extremely leery of previous PM Manmohan Singh and his overt diplomatic and emotional tilt toward Japan and, with good reason, has expected the current officeholder, Nadendra Modi, to play off China, Russia, and the United States in a more pragmatic manner.

This, indeed, was the takeaway from President Obama’s recently concluded trip to India.

President Obama’s decision to accept Prime Minister Modhi’s invitation to attend the Republic Day extravaganza further buttressed Modi’s prestige and popularity within India and elicited a wave of “Mobama” triumphalism in the press, much to China’s discomfiture. However, in the end, Modi played true to form by publicly and bluntly rejecting President Obama’s call to limit India’s greenhouse gas emissions.

For the PRC, an important area of anxiety is Arunachal Pradesh and the threat that India might “internationalize” the bilateral border dispute by canvassing its actual and would-be allies for support on the issue, perhaps even to the extent of going tit-for-tat with Japan i.e. India backing Japan on the issue of Senkaku sovereignty in return for Japanese aid and comfort on AP. However, it looks like Japan—like the Asian Development Bank, which ran into a PRC buzzsaw when it tried to put an Arunachal Pradesh hydropower project on its agenda in 2009—is not quite ready to mix it up on AP.

Let’s unpack the Arunachal Pradesh issue. I’ve written a lot about Arunachal Pradesh. It’s a complicated situation and I scattered my narrative over a handful of posts: “China ‘pivot’ trips over McMahon Line,” “Charm Offensive: China’s Flank of Discontent,” and “India Places Its Asian Bet on Japan: Roiling the Waters of the Asia-Pacific.”

To summarize. Arunachal Pradesh is a region controlled by India in its northeast quadrant, between Bhutan and Burma, home to a variety of ethnic groups. One of those groups is Tibetan, centered on the town and district of Tawang in the western end of AP at the border with Bhutan.

The Arunachal Pradesh dispute is bookended with Aksai Chin, a blasted desert between India and the PRC in the northwest, and is controlled by the PRC. The Indian claim to Aksai Chin is not terribly robust, since it is based on an internal British Indian survey—the Johnson Line—which was never discussed or agreed with China. The PRC built a strategic road across Aksai Chin in the 1950s, and it took several years for the Indian government to even find out it was there.

There is a third slice of disputed territory, the “Trans-Karakorum Tract” bordering Kashmir, geographically distinct from Aksai Chin, which India claims Pakistan illegally ceded to the PRC in a land swap. For some reason, the PRC and India aren’t arguing about this piece. Both Arunachal Pradesh (AP) and Aksai Chin territories have been openly disputed since before the 1962 Sino-Indian war. The PRC has at times offered a grand bargain in which the two sides acknowledge each other’s regions of effective control, by which India got AP and the PRC gets AC. The official Indian response has been nothing doing and all territory it lost in the 1962 war must be recovered i.e. Aksai Chin is not negotiable. It has decoupled the two issues, and has focused its diplomacy on the insistence that its sovereignty over AP be confirmed. India’s claim to AP is complicated in an interesting way.

In 1914, Great Britain was interested in creating an autonomous Tibetan buffer—“Outer Tibet”—between British India and Russia/China. To this end, Sir Henry McMahon, the Foreign Minister of British India, invited Tibetan and Republic of China delegates to the Indian town of Simla. Tibet, eager to be acknowledged as an autonomous power with its own rights to negotiate directly with foreign powers (and not just through China), generously conceded a delineation of Lhasa’s sphere of control—the McMahon Line–that alienated Tawang, a market town that interested the Raj, to British India.

However, the Simla Agreement was negotiated between the Tibetan and British representatives in a provisional sort of way after the Chinese representatives had packed up and left. Since Britain’s Foreign Office was protective of its China diplomacy and not interested in encouraging Tibetan pretensions to negotiate as an independent sovereign power, the absence of the Chinese representatives—and a Chinese endorsement of the border arrangement accepted by the Tibetan authorities–was a deal breaker.

The Simla Agreement was apparently treated as an aspirational document and was recorded in the most authoritative compendium of British Indian treaties, Sir Charles Umpherston Aitchison’s Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Sanads, with the notation that neither Great Britain nor China had ratified the treaty. Since Tibet wasn’t recognized as a sovereign power, whatever it hoped to achieve with the Simla Accord—and what it had tried to give away, namely Tawang– was, in the eyes of the British, moot.

Things puttered along until 1935, when the detention of a British spy in Tawang by Tibetan authorities awakened the cupidity of a diplomat in the Foreign Office of British India, Olaf Caroe. Caroe checked the files, found that Great Britain had no ratified claims on Tawang, and decided to amend and improve the record. He arranged for the relevant original volume of the 1929 Aitchison compendium to be withdrawn from the various libraries in which it was filed, discarded, and replaced with a new version—but one that still claimed to be compiled in 1929, thereby removing the need for awkward explanations or documentation concerning why the switch had happened. The spurious version claimed that Tibet and Britain had accepted the treaty.

The deception was only discovered in 1964, when a researcher was able to compare one of the last three surviving copies of the original compendium, at Harvard University, with the spurious replacement. Unfortunately, that was too late for Nehru, who staked his security strategy and his diplomatic exchanges with China to a significant extent on the fallacy that he had inherited from British India a clear and unequivocal claim to its borders.

In 1962 Nehru decided to move up military units to assert India’s claim to territory in Ladakh/Aksai Chin and up to the McMahon Line in Arunachal Pradesh under a gambit optimistically named The Forward Policy. The PRC begged to differ—and Chairman Mao was itching to stick it to India’s patron, Nikita Khrushchev–and attacked. India’s entire strategy had been predicated on the assumption that the PRC would not respond (shades, I think, of Western confidence that Vladimir Putin would stay his hand in eastern Ukraine out of fear of sanctions and the wrath of his impoverished and disgruntled oligarchs) and the Indian Army, outnumbered, undersupplied, and disorganized, was completely unprepared to fight for the high ground in the north.

India suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the PLA. After its victory, the PRC decided to take the high ground, diplomatically as well as geographically. It withdrew its forces to behind the McMahon Line and offered a swap of AP for AC. No dice, as we have seen. India clearly does not see any need to credit AP—territory that the PRC abandoned—as any kind of bargaining chip concerning Aksai Chin. This is, perhaps, a cautionary tale to the PRC as to the geostrategic minuses as well as pluses of trying to behave like Mr. Nice Guy.

This history is officially persona non grata in India. The report the Indian government commissioned on the 1962 war—the Henderson Brooks Report–was so devastating to India’s position and its legal, military, and diplomatic pretensions it was promptly banned and publication is forbidden to this day. In an ironic recapitulation of the case of the Atchison compendium, it was assumed that there were only two typewritten copies and they were securely buttoned up in safes in New Delhi. However, the Times of London correspondent, Neville Maxwell, got his hands on a copy and used it to write an expose on the tragedy of errors in 1962, India’s China War, thereby earning himself the fierce hatred of generations of Indian nationalists.

Maxwell tried several times to put the report into the public domain. As quoted in Outlook India, Maxwell provided an interesting account of how the freedom of expression sausage gets made when the information involved is not necessarily a matter of national security (the report is classified Top Secret, but its content—the minutiae of military decisions and movements sixty years ago have no current strategic or tactical significance) but is a matter of supreme political embarrassment (to Nehru, the Congress Party, the Gandhi political dynasty, and to the army).

My first attempt to put the Report itself on the public record was indirect and low-key: after I retired from the University I donated my copy to Oxford’s Bodleian Library, where, I thought, it could be studied in a setting of scholarly calm. The Library initially welcomed it as a valuable contribution in that “grey area” between actions and printed books, in which I had given them material previously. But after some months the librarian to whom I had entrusted it warned me that, under a new regulation, before the Report was put on to the shelves and opened to the public it would have to be cleared by the British government with the government which might be adversely interested! Shocked by that admission of a secret process of censorship to which the Bodleian had supinely acceded I protested to the head Librarian, then an American, but received no response. Fortunately I was able to retrieve my donation before the Indian High Commission in London was alerted in the Bodleian’s procedures and was perhaps given the Report.

In 2002, noting that all attempts in India to make the government release the Report had failed, I decided on a more direct approach and made the text available to the editors of three of India’s leading publications, asking that they observe the usual journalistic practice of keeping their source to themselves…To my surprise the editors concerned decided, unanimously, not to publish…Later I gave the text to a fourth editor and offered it to a fifth, with the same nil result.

Narendra Modi, a determined foe of the Congress Party and the Gandhis (I had to chuckle when I read these fawning articles about President Obama bonding with Prime Minister Modi over their shared Gandhi love, despite the awkward fact that Modi’s BJP nationalist party had been and apparently still is the spiritual home of Gandhi’s assassin), came to power promising to release the report, but didn’t. And when Maxwell posted part of the report on his website, the site was symbolically blocked.

The Indian army, in particular, is wedded to a creation myth of PRC perfidy that is infinitely more utile than acknowledging that the PLA attack, rather than unprovoked, was a response to a strategically and diplomatically bankrupt Indian border gambit compounded by non-stop miscues by India’s civilian leadership and a disastrous defeat for its military forces.

In 2005, the PRC and India started negotiations over the borders issue. Here’s a nice explainer from the Daily Mail! in 2013 which signals that Aksai Chin might be on the table, but Tawang is off the table, and unfortunately omits the significant complication of the Caroe forgery.

India’s move into Arunachal Pradesh in the 1950s is less than a slam dunk according to international law, complicated in particular by the issue of Tawang. Not only is there the problem of Olaf Caroe’s bibliographic hijinks, there is the awkward fact that India forcefully displaced Tibetan theocratic rule in Tawang—nominally rule from Lhasa, actually local rule by the immensely powerful monastery.

Lhasa had apparently experienced cartographic remorse over Simla and implored India to recognize Tawang as Tibetan territory in 1947. Instead, India seized the district in 1951 in a quasi-official/quasi-military “liberating the Tibetan serfs” operation rather similar to what the PRC conducted in its part of Tibet.

In recent years, the Dalai Lama has been forced into the unpleasant position of affirming Indian sovereignty over Tawang, whose great monastery (the second largest in Tibetan Buddhism) first gave him shelter when he fled PRC control in 1959, and which had hosted the reincarnation of the 6th Dalai Lama way back when.

The Dalai Lama apparently verbally acknowledged, if not in writing, that AP and Tawang belonged to India on several occasions while he still served at the apex of power in the Tibetan government in exile (a position he relinquished in 2011). However, I assume twisting the Dalai Lama’s arm to concede Indian sovereignty over Tawang falls a little bit short, since the Tibetan government-in-exile lacks international recognition (and with it the right to cede territory to India).

The PRC is happy to harp on Tawang’s role in the AP situation, since it serves as a continual reminder that India is occupying territory in AP that, however you slice it, is a core component of the Tibetan homeland, thereby keeping alive a non-Indian or, if you want, a PRC-cum-Tibet claim to at least part of the region and attempting to balk India’s attempt to claim full sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh under international law.

To understand how this relates to the Senkakus requires reflection on another piece of suppressed history—that the United States returned the Senkakus to Japanese administrative control not sovereignty in 1973 as part of the Okinawa package with the stated expectation that the sovereignty of the rocks would be negotiated between China and Japan.

My personal opinion is that the PRC is in no hurry to unfreeze the conflict over Arunachal Pradesh, and its insistence on sovereignty over Tawang—a district, I suspect, that has extremely limited interest in reunification with the Chinese motherland—is something of a pretext. With the Simla Agreement tainted and no subsequent cession of Tawang by Tibet or China, the Indian position in Tawang is embarrassingly similar to that of the PRC in the matter of the Spratlys i.e. having expelled the previous rulers by conquest and achieved control of the territory without attaining international recognition of its sovereignty. And it’s somewhat similar to the Senkakus, where the United States effectively surrendered its sovereignty over the islands when it returned Okinawa and the Ryukyus to Japan, but didn’t cede its claim to anybody else.

Maybe Arunachal Pradesh is another one of those Mexican-standoff situations like Kashmir vs. Tibet (a.k.a. the Indian temptation to make mischief in the ethnic-Tibetan areas of the PRC is inhibited by concern that the PRC, via Pakistan, might light the fuse in Kashmir). The PRC keeps the Tawang/AP issue alive to forestall thoughts by India of giving aid and comfort to Japan on the Senkakus or, for that matter, Vietnam on the Spratlys.

Both the PRC and India are bulking up their infrastructure and military on their respective sides of the de facto McMahon-Line-based border, making it a virtual certainty that India will never alienate any part of AP, including Tawang. That’s good news for reduced actual tensions (as opposed to defense ministry posturing) at the shared border, but India’s heightened sense of security concerning Arunachal Pradesh may encourage it to be less tentative vis a vis the PRC in its Japanese and Vietnamese diplomacy.

So, paradoxically, greater security along the PRC-Indian border may lead to greater insecurity elsewhere.