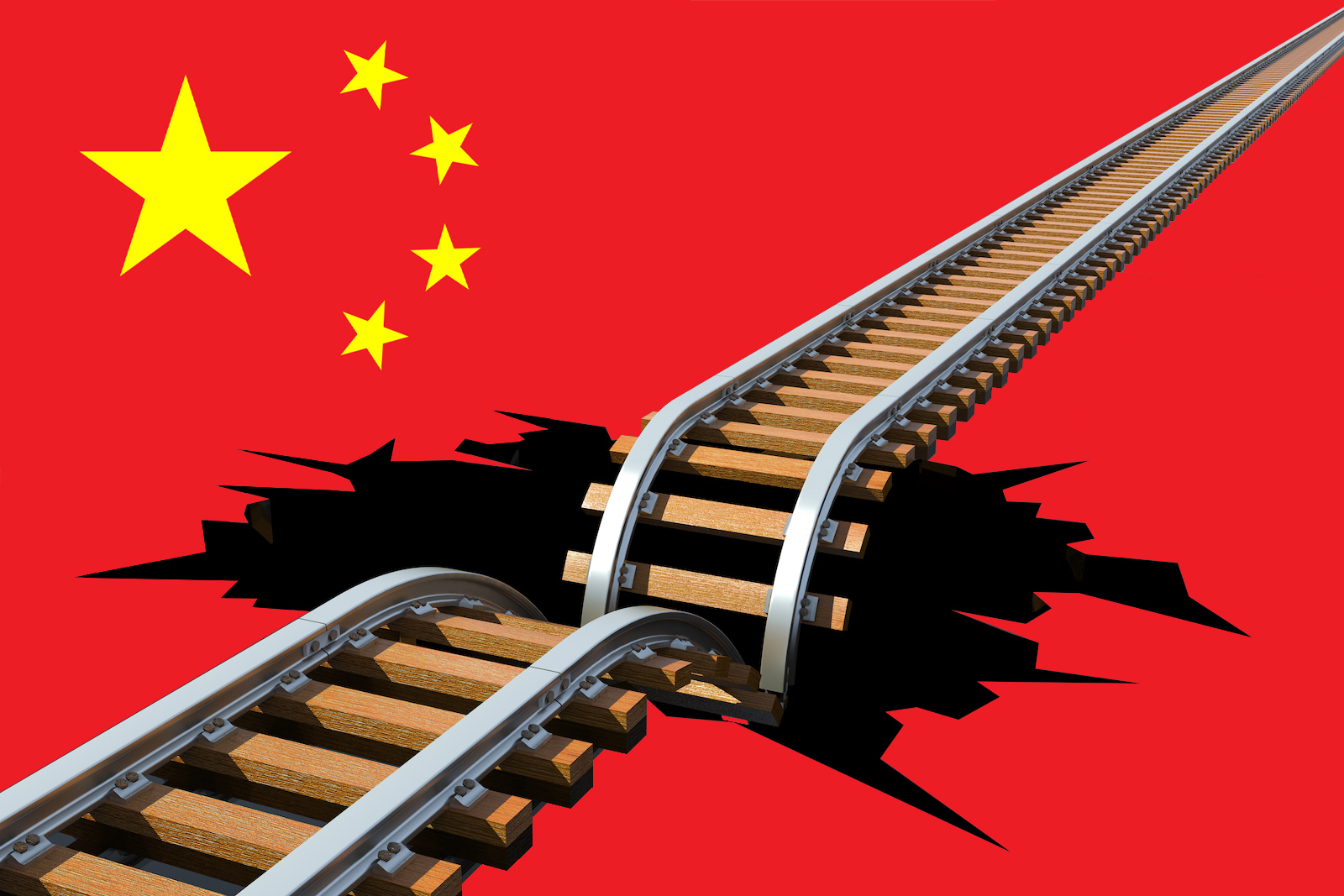

Is China Souring on its Belt and Road Initiative?

China’s investments in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have dramatically decreased since 2019. The Global Development Policy Center at Boston University estimates that China’s foreign aid spending was $3.9 billion in 2019, a significant decrease from the $75 billion spent in 2017. As disputes over the implementation of projects have grown, tensions with the West have risen, and China’s internal economic position has gotten worse, many have said that this decline marks the end of the BRI. The BRI’s demise has, however, been widely exaggerated. The BRI has a part to play in the shifting of global supply chains even in the current period of deglobalization of trade and rapid decoupling between China and the West.

The BRI, or the various infrastructure projects arranged inside the BRI framework, have not disappeared from the political imaginations of policymakers in Beijing, especially not in recipient countries. Ironically, many of the BRI’s projects are necessary for a successful decoupling from China, which is the major reason the BRI continues to be a topic of political discussion even as investments decline.

Decoupling from the Chinese industrial engine is impossible without bridging the infrastructure gap in low- and middle-income nations. Therefore, developing nations were still willing to continue to improve their trade infrastructure to entice investments migrating away from China as trade tensions between China and the United States continued to increase from 2017 onward. For example, Vietnam, Thailand, and the rest of Southeast Asia are capitalizing on BRI infrastructure to attract foreign investors fleeing geopolitical risks.

Similar to how Chinese businesses benefit directly from improved infrastructure abroad that is financed by Chinese money, Chinese businesses also benefit directly from greater tariffs and rising salaries at home. Instead of decoupling, the Chinese supply chain is growing internationally. To draw foreign direct investment into its newly constructed industrial parks, Ethiopia, an industrialising nation that until recently was hailed as the new centre for garment and apparel manufacturing, relied significantly on Chinese infrastructural projects. Chinese fashion and clothing companies that couldn’t afford to produce in China have mostly settled in these industrial parks; these Chinese companies then export their Ethiopian-produced goods to Europe and the United States.

In terms of politics, this calls into question the usefulness of “near-shoring” or “friend-shoring” as a supply chain tactic. In the end, customers still buy a Chinese-designed and -made product, despite the label reading “Made in Ethiopia.” Thus, the BRI has contributed to increased connectivity between low-income countries and Western end markets in addition to facilitating more commerce and interactions with China.

However, as tensions increase, Chinese investors and businesses are being barred from more international economic sectors. This is evident from the present disputes over the sale of a stake in the German port of Hamburg to COSCO Shipping and the United States’ escalation of the chip wars. These incidents may cause the BRI policy to take a more direct and combative stance. This could hasten the process of deglobalization and have a detrimental effect on low- and middle-income nations, which depend on sizable consumer end markets to expand their exports. Countries that receive benefits from the BRI gain from strategic uncertainty rather than having to pick sides in a bipolar world system.

I contend that up to this point, despite accusations to the contrary, China has not turned the BRI into a weapon. To the detriment of low-income nations, Chinese businesses, end-user customers, and the global economy, actual threats of weaponization of BRI infrastructure can, nevertheless, materialise as we approach the 10th anniversary of the BRI and tensions continue to grow.