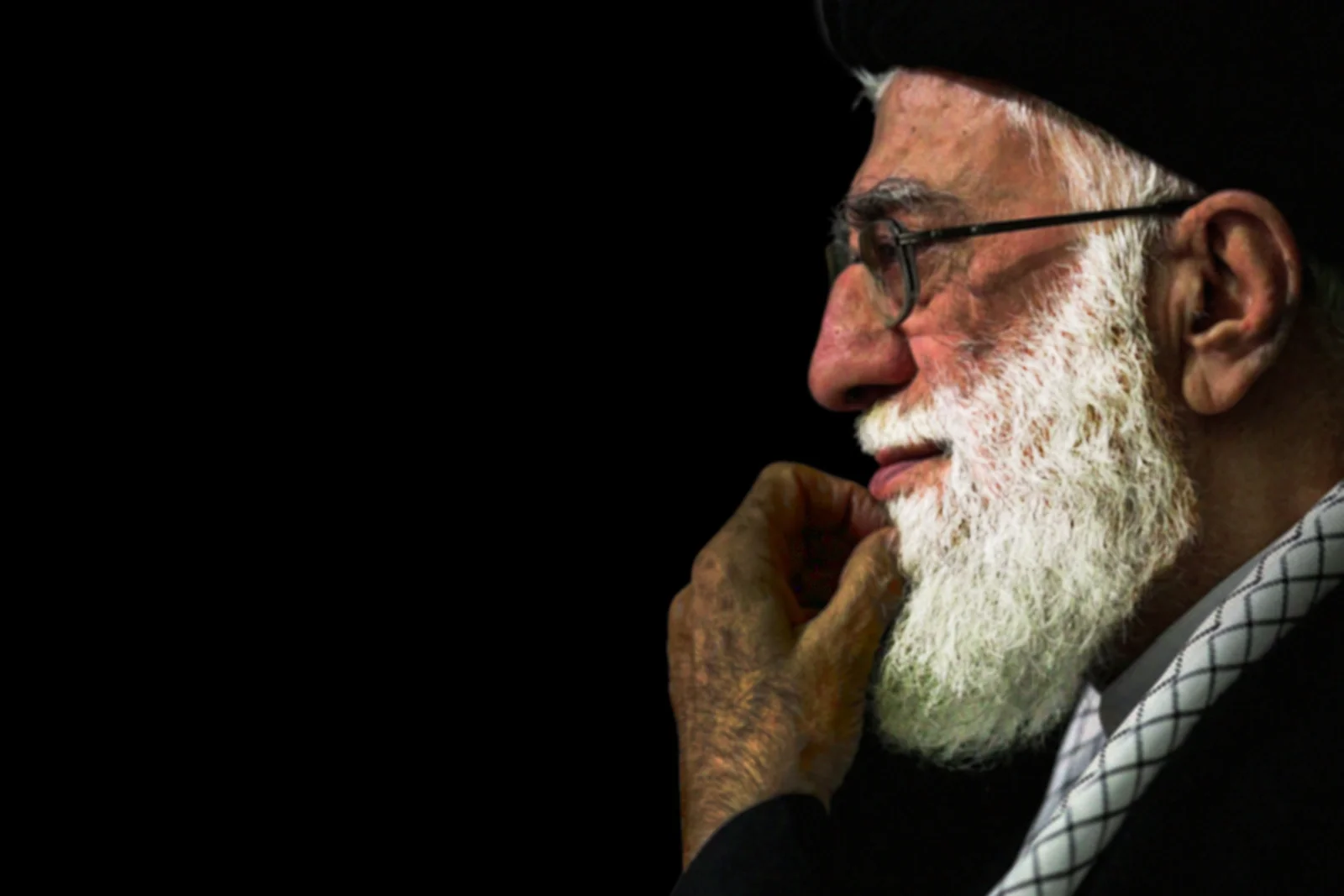

Is Khamenei Rethinking the Nuke?

The considerable damage inflicted on Iran’s proxy groups has prompted Tehran to reassess its deterrence strategy. Prominent voices within Iran’s security establishment are now urging Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to reconsider his fatwa, which declares nuclear weapons incompatible with Islam. What was once framed as a principled opposition to nuclear weapons now appears to have been little more than a strategic maneuver in negotiations.

A telling episode from the Iran-Iraq War suggests that Tehran once genuinely adhered to Islamic prohibitions against nuclear and biological weapons. However, evolving international pressures have driven many within Iran’s security apparatus to prioritize pragmatism over the Islamic ideals from which they derive legitimacy.

Khamenei issued his nuclear fatwa on March 20, 2003, in an apparent effort to assuage U.S. concerns as Washington waged war in neighboring Iraq. Declaring Iran’s opposition to nuclear arms, he stated: “We do not want an atomic bomb, and we are even against having chemical weapons. Even when Iraq was attacking us with chemical weapons, we did not attempt to produce chemical weapons. These issues do not agree with our principle.”

Later, he elaborated on his stance, citing religious doctrine: “According to our fundamental beliefs, our religious principles, using such means of mass destruction is absolutely prohibited. This is the destruction of crops and offspring, which the Quran has forbidden.” He referenced a Quranic verse condemning the killing of children and the destruction of crops: “If he were to wield authority, he would try to cause corruption in the land and to ruin the crop and progeny.”

Khamenei’s fatwa gained international prominence when Iran’s delegation to the International Atomic Energy Agency cited it as the reason for Iran’s opposition to nuclear weapons: “The Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has issued the fatwa that the production, stockpiling, and use of nuclear weapons are forbidden under Islam and that the Islamic Republic of Iran shall never acquire these weapons.”

Yet, Tehran’s purported opposition to nuclear and biological weapons does not hold up under scrutiny. Classified documents released by WikiLeaks reveal that Iran had stockpiled 20 metric tons of sulfur mustard and four metric tons of nitrogen mustard agents. Although Iranian officials claim these stockpiles were later destroyed to comply with the Chemical Weapons Convention, Tehran’s actions in Syria paint a different picture. Despite mounting evidence that former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad deployed chemical weapons against civilians—including the infamous sarin gas attack on Eastern Ghouta that killed 1,127 people—Iran was a steadfast supporter.

Tehran even attempted to block a U.S.-led condemnation of Assad at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). However, the U.S. forced a vote, successfully passing the measure and isolating Iran diplomatically. Beyond shielding Assad from international condemnation, Iran provided between $30 billion and $50 billion to prop up his government. Iranian support extended beyond financial aid, supplying Assad’s military with weapons, equipment, and personnel.

While the Iranian regime presents Khamenei’s fatwa as an ironclad commitment against nuclear weapons, key figures within Iran’s security establishment have repeatedly suggested that the ruling is flexible. On February 10, 2022, Mahmoud Alavi, then Iran’s Minister of Intelligence, stated: “Our nuclear industry is peaceful, and the fatwa of the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution has also declared nuclear weapons haram [forbidden], but if the Islamic Republic of Iran is pushed in that direction, it is no longer Iran’s fault, but the fault of those who have pushed Iran.”

Alavi’s position is not an outlier. Amir Mousavi, director of Iran’s Center for Strategic Studies and International Relations, echoed this view: “In the school of Ahl al-Bayt, the fatwas that mujtahid scholars like Imam Khamenei issue are for specific circumstances. If these circumstances change, the fatwa may also change.” In other words, the Iranian regime invokes the fatwa to project an image of moral opposition to nuclear weapons, even as its policies contradict the very Islamic principles it claims to uphold.

Iran’s use of the fatwa as a diplomatic tool contrasts sharply with the unwavering stance of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic. During the Iran-Iraq War, Khomeini was resolute in his rejection of chemical weapons, even as Iraqi forces unleashed chemical attacks on Iranian civilians. In a 2014 interview with journalist Gareth Porter, Mohsen Rafighdoost—a founding member of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and Khomeini’s military procurement chief—recounted proposing nuclear and chemical weapons research to the Ayatollah. Expecting approval, he was shocked when Khomeini dismissed the proposal outright.

According to Rafighdoost, Khomeini declared: “It is haram to produce such weapons. You are only allowed to produce protection.” When pressed on the matter of nuclear weapons, Khomeini was unequivocal: “Don’t talk about nuclear weapons at all.”

Even after Saddam Hussein’s forces devastated Iranian cities like Sardasht with mustard gas—leaving 8,025 of its 12,000 residents exposed—Khomeini remained firm. In explaining his rationale for ending the war, he cited Iraq’s extensive use of chemical weapons and Iran’s inability to counter them as key factors, despite previously vowing to “fight on until the infidels are defeated.”

Today, Iran’s security establishment views Khamenei’s fatwa as a strategic asset rather than a moral obligation. Tehran’s continued support for Assad, despite his documented use of chemical weapons, undermines any claims of principled opposition to nuclear weapons. While one could argue that Iran’s wartime leadership adhered to Islamic teachings in rejecting such devastating weapons, the current regime operates with a far more flexible interpretation—one shaped by political expediency rather than religious conviction.