Is there Something Rotten in the State of Nigeria?

Doing business with emerging economies is a risky business for company profits and reputation. China’s own aggressive foreign direct investment policies in Africa have polarised opinions, with many seeing it as a front for their soft power push.

However, choosing where to invest in countries with poor infrastructures is by no means easy. To help businesses, there are whole professions dedicated to assessing the pros and cons of investing abroad. Whilst many economic commentators espouse the merits of investing in Africa, Nigeria is at the top of the pile of states marked “don’t invest here.”

While many see 2023 as a chance for a fresh start, the Nigerian government might find itself too mired in past scandals to think about the future. The eyes of the world will be focused on Nigeria in January.

Not only does the Nigerian government face a change in leadership with presidential elections slated for February, but it is also facing an eight-week trial in a London court. A trial where it faces paying £8 billion to Process and Industrial Developments Limited (P&ID), an Irish company, for illegal breach of contract.

This represents one of the largest arbitration amounts ever owed by a state and at the time, is now equivalent to 30% of Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves.

Ten years ago, P&ID began arbitration action against the Nigerian government for breach of contract after the government failed to begin construction on a gas processing plant in southern Nigeria.

After five years of hearings, P&ID was awarded almost £5.5 billion in lost profits from the project at an interest rate of 7%. Nigeria failed to pay and appealed the ruling and two years later, P&ID got permission from UK courts to seize Nigerian assets as payment instead.

This produced a public outcry in Nigeria and the government began making outlandish allegations that P&ID had scammed them into the contract. These allegations have extended court proceedings for another four years and the appeal will be heard in a London court in January.

This unreliability has led to a long line of payouts to international businesses, the most recent of which was a failed $1.7 billion claim against JP Morgan. However, this conduct doesn’t only come at a financial cost. It also causes reputational damage among foreign investors, who are less and less likely to invest in Nigeria.

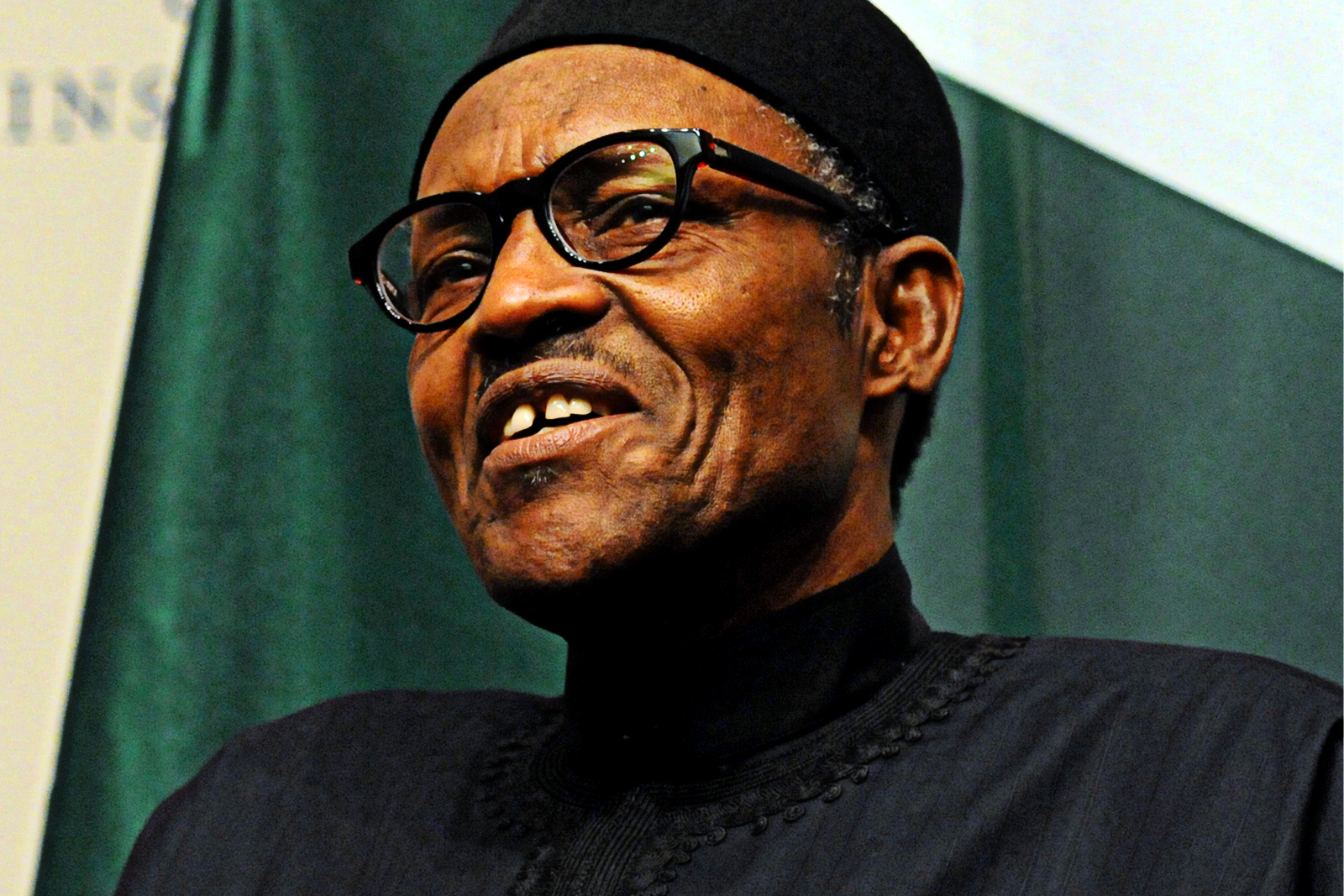

Sadly, the pattern looks unlikely to improve with the next election. Despite running on an anti-corruption platform, the Buhari government itself has become embroiled in the very corruption it sought to tackle, with Buhari’s own son-in-law subject to multiple allegations of corruption and improper behaviour.

This case doesn’t just raise concerns about investing in foreign countries. It also raises concerns about how foreign countries are using the UK court system to leave businesses out of pocket.

The case has shown a pattern of refusal by Nigeria to accept and abide by legal judgment or awards against it. Not only did the government refuse to make the payments owed for two years but they only sought to fortify their legal defences when they were no longer able to withhold the payments from P&ID.

Worse still, they have also worked to seriously undermine the rule of law when it opposes their interests. The former head of Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, who was himself arrested on corruption charges in 2020, stated that the UK commercial court and judge should be investigated for previous judgments against the Nigerian government.

Others have accused the UK courts of being neo-colonialist and of wanting to impose ‘punitive’ judgment on Nigeria. With this kind of attitude, it is unlikely that the Nigerian government will accept any judgment against them, let alone make the payments they owe.

By dragging out the proceedings, the Nigerian government is using up valuable British courts’ time and resources on a case with only one outcome that they will accept as legitimate. This is particularly detrimental at a time of significant court backlog following the pandemic.