Jerry Goldsmith: A Tribute to His Music

Ten years after legendary film composer Jerry Goldsmith’s passing, his music still flourishes in the hearts of multitudes. “Ce qu’on ne peut dire et ce qu’on ne peut taire, la musique l’exprime,” said French poet Victor Hugo in William Shakespeare (1864). Translated, “What demands words but defies them, music delivers.” A Goldsmith score can speak with a novel’s force.

Goldsmith began studying the piano at age six. At thirteen, he studied theory, harmony, and counterpoint under private tutelage. “I was fourteen or fifteen and I went to see Spellbound and I fell in love with Ingrid Bergman and I fell in love with Miklós Rózsa’s score,” Goldsmith said. “So I decided then I was going to marry Ingrid Bergman and I was going to write music for films. So half my dream came true.”

During the ensuing decades, Goldsmith composed over two hundred scores for film and television. One of his greatest abilities was tracing the emotional arc of an entire film in just the main title music.

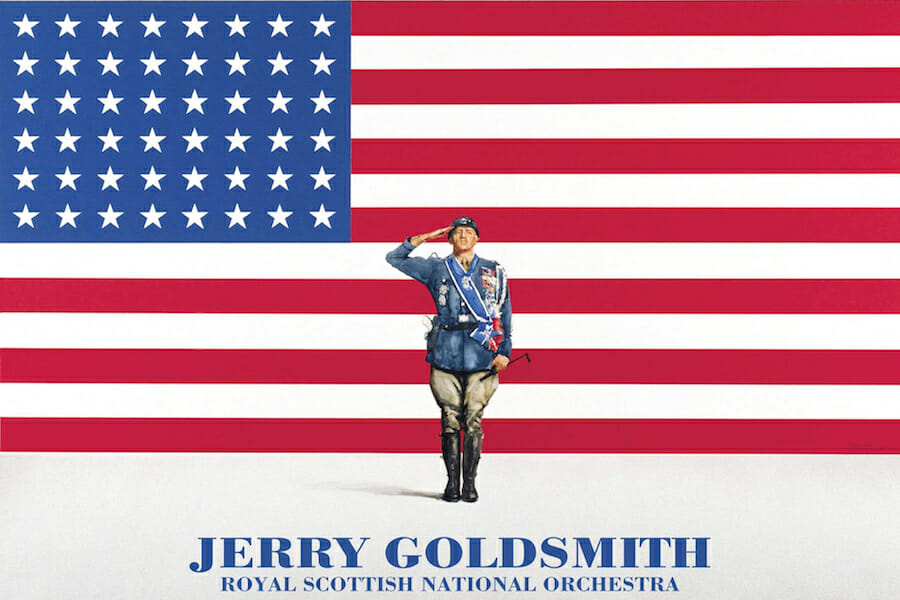

The main theme to Patton (1970) voices all sides of the titular character General George S. Patton—his belief in reincarnation, his career proximity to death, and his adoration of glory. The brass conveys the braggadocio and the organ conveys the dirge. In the opening theme to Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), the orchestra speaks to Japan’s role in World War II. A koto plays a sinister melody and then passes it to brass. The theme strengthens with each refrain, expressing the inevitability of a devastating attack on Pearl Harbor. The primary theme to Chinatown (1974) evokes the mystery and intrigue of the film noir genre. The opener to Rudy (1993) articulates the innocence and pride of a boy on the gridiron.

One of the most memorable of Jerry Goldsmith’s creations was the theme to Star Trek, first announced in Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). When asked what attracted him to the franchise, Goldsmith responded, “It’s a broad romantic canvas. Star Trek is very operatic as far as I’m concerned. It’s one of the few things that’s bigger than life. The whole story is about a better world—a peaceful world and a better life. The whole moral of it is really quite uplifting.” His theme for the franchise strikes notes of nobility, power, and discovery all at once.

Goldsmith was so prolific that a comprehensive study of his masterworks could occupy the span of years. One lightly studied but sumptuous score is Medicine Man (1992). The film concerns two research scientists searching for a cure for cancer in the Amazon jungle. On album, the cue called “The Trees” is one of Goldsmith’s finest. It begins as a playful melody on violin, accented by harp and piano. Then, with a cymbal crash, the melody rises to a gorgeous crescendo. The rainforest is given sweeping orchestral voice.

Another forgotten gem in Goldsmith’s oeuvre is his music for The Russia House (1990), an adaptation of a John Le Carré novel. The film’s spy games between the Soviet Union, England, and the United States are underscored by jazz. The saxophone sizzles, the bass rumbles, and the violins pine. Every shade of gray in Le Carré’s world is evident.

Goldsmith could score films of military conquest, space exploration, and superheroism. He could also write music for jibes and giggles. His penultimate score was for Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003).

Goldsmith’s taste in humor was broad and conducive to storytelling. According to Film Score Monthly, he once described an occasion when producers balked at his music at a preview screening. “When the producers asked what might be wrong with the film, they eventually concluded that it was the fact that the music was written in a minor key. The solution came when the studio (MGM) directed its music department to write no further music with any minor chords!” Another story of his involved “some producer who thought all one had to do to get a French flavored score was to use more French horns!”

Goldsmith’s talent and productivity inspired respect and perhaps a little awe from colleagues. Director Joe Dante, nine-time collaborator with Goldsmith, recalled, “I don’t know if I’ve worked with any geniuses in this business, but if I have, it would be Jerry. The scope and breadth of what Jerry achieved in his career is just phenomenal. He was the luckiest find I ever made in movies. He was just so brilliant.” Henry Mancini, himself a virtuoso composer known for his Pink Panther theme, said of Goldsmith: “He has instilled two things in his colleagues in this town. One is, he keeps us honest, and the other one is, he scares the hell out of us.”

Goldsmith rarely defined his compositional method. Admirers were forced to listen to his music and wonder how and why. When he sat down to write, Goldsmith counted on his emotional intelligence and instincts to lead him to the right music. Of the score for Planet of the Apes (1968), he said, “You have to be careful that the music slides into a scene, plays a scene, enhances a scene, but is not intruding on a scene. And there is a difference. It’s not an intellectual difference, it’s an emotional difference.” On composing QB VII (1974), a TV miniseries about the Holocaust, Goldsmith explained, “I have to go by my instincts in whatever I do. They’re much more reliable than my conscious mind.”

Method is for the head; Goldsmith wrote for the heart. He made melodies the way Shakespeare made plays—with vision for life’s multifarious tapestry. Both artists opened wells of tragedy, history, comedy, and romance at the whim of their pen. Shakespeare wrote for the groundings and for the king; Goldsmith scored Bugs Bunny and King Arthur.

Goldsmith excelled at the grandest canvass. He wrote for starships accelerating to light speed and vanishing in a brilliance of white. To journey through his music is to journey without end.