Books

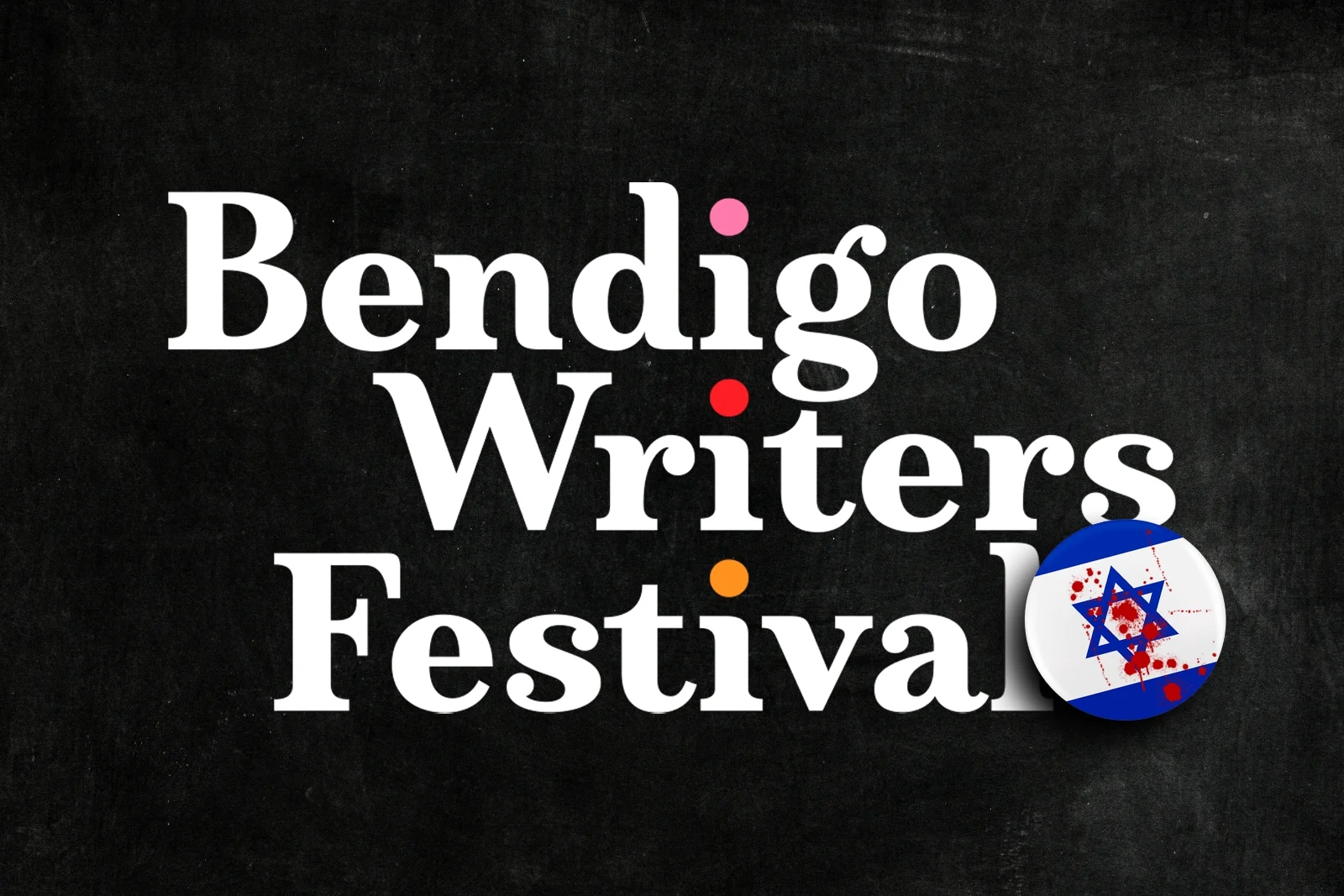

Lethal Nonsense: Antisemitism, Codes of Conduct, and the Bendigo Writers Festival

Write, but do not offend. Speak and comment, but do not divide. Observe cruelties, barbarities, and murder, yet refrain from having an opinion. This is the constipating, stifling regime being put in place via suggested codes of conduct for organisers of writer events in Australia. The object of this intellectual veiling: discussing the exterminating war in Gaza. Across the country, the straitjacket of forced social harmony is being applied.

The Bendigo Writers Festival, being held in Victoria, Australia, is the latest case point, joining the Sydney Writers Festival, Melbourne Writers Festival, the Perth Writers’ Weekend, the Sydney Opera House’s All About Women, and Adelaide Writers Week in the controversy league tables. Free speech and academic freedoms have come to be seen as increasingly dangerous, necessitating the culling and silencing of ideas. While such events are rarely controversial and mostly tepid affairs, filled with the clubbable types who rarely bathe in the bracing waters of controversy, this year’s event promised to be a bit different. Wars of liquidation and conquest are up for discussion, and the organising committee, the Greater Bendigo City Council, was worried. Add La Trobe University to the organisational mix, an institution that has a proven record in intellectual cowardice and managerial paranoia, then cracks are bound to appear in the edifice.

On August 13, writers received an email from the organisers warning participants in La Trobe Presents panels that they must adhere to the university’s code of conduct. For those familiar with such vexing instruments, they are designed to preserve a fetid status quo approved by university politburos, concealing the mischief of a white-collar criminal class while punishing the curious and the questioning. The language used is almost always infantilising and demeaning, potty training for naughty types.

Under the “Inclusivity and Diversity” section of the code, those involved in the festival would have to comply “with the principles espoused in La Trobe’s Anti-Racism Plan, including the definitions of antisemitism and Islamophobia in the Plan.” The definition of antisemitism adopted by La Trobe is one approved by Universities Australia and the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, high bastions of lexical, censoring lunacy: “For most, but not all Jewish Australians, Zionism is a core part of their Jewish identity. Substituting the word ‘Zionist’ for ‘Jew’ does not eliminate the possibility of speech being antisemitic.” The code of conduct also notes the requirement to engage in the sedating atmosphere of “respectful engagement”: “Avoid language or topics that could be considered inflammatory, divisive, or disrespectful.” Best not think too much, then.

The potty training missive prompted a surge of indignant withdrawals, among them Randa Abdel-Fattah, Evelyn Araluen, Maddison Griffiths, Jacinta Le Plastrier, Jess Hill, Thomas Mayo, and Cher Tan. Abdel-Fattah’s letter announcing her withdrawal from the event attacked the adopted definition as one that “conflates anti-Zionism and antisemitism.” It also censored “public debate on Israel’s violations of international law” and “directly infringes on my right to speak as a Palestinian as well as my freedom of speech and academic freedom.” The author also declared that she could not participate “in any festival that asks me to endorse a framework that demands my self-censorship. At a time when journalists are being permanently silenced by Israel’s genocidal forces, it is incomprehensible that a writers’ festival should also seek to silence Palestinian voices.”

Araluen also took issue with the infringing nature of the antisemitism definition. As a First Nations woman, she was obligated to speak out against oppression, “which includes speaking out against Israel’s ongoing UN-defined genocide of the Palestinian people.”

Hill, an investigative journalist, wondered why authors could be invited to speak if they were deemed unreliable agents of responsible debate. “The message we’re sending is if you try to restrict speech at a festival of ideas in the future, the very viability of our festival will be at risk.” A joint statement from Hill and authors Sonya Orchard and Kirstin Duncanson announcing their withdrawal from their scheduled event, Not On, which would have discussed violence against women and children, argued that “the Festival’s newly issued Code of Conduct has made our participation impossible.”

The Human Rights Law Centre was also approached by certain festival participants regarding the adopted antisemitism definition and their fears about its application. This prompted the body to seek “urgent clarification” from the organisers as to how the provision within the code would be treated, notably on such topics as First Nations sovereignty, feminism and women’s rights, statements accusing Israel of committing crimes against Palestinians, and critiques of Zionism.

On August 14, a spokesperson for the Bendigo Writers Festival provided a statement to Crikey professing its commitment “to holding an event that engages in respectful debate, open-minded discussion, and explores topical and complex issues.” Scrappy, cerebrally lethal terms such as “safety and well-being” were to be emphasised as “necessary.” Codes of conduct were useful points of reference “to guide expectations for respectful discussion, particularly when exploring past and current challenging, distressing and traumatic world events.” Those withdrawing from the festival were breezily thanked “for their initial willingness” to be involved, while the festival, albeit with an adjusted program, would continue. How fitting it would be if no one turned up.