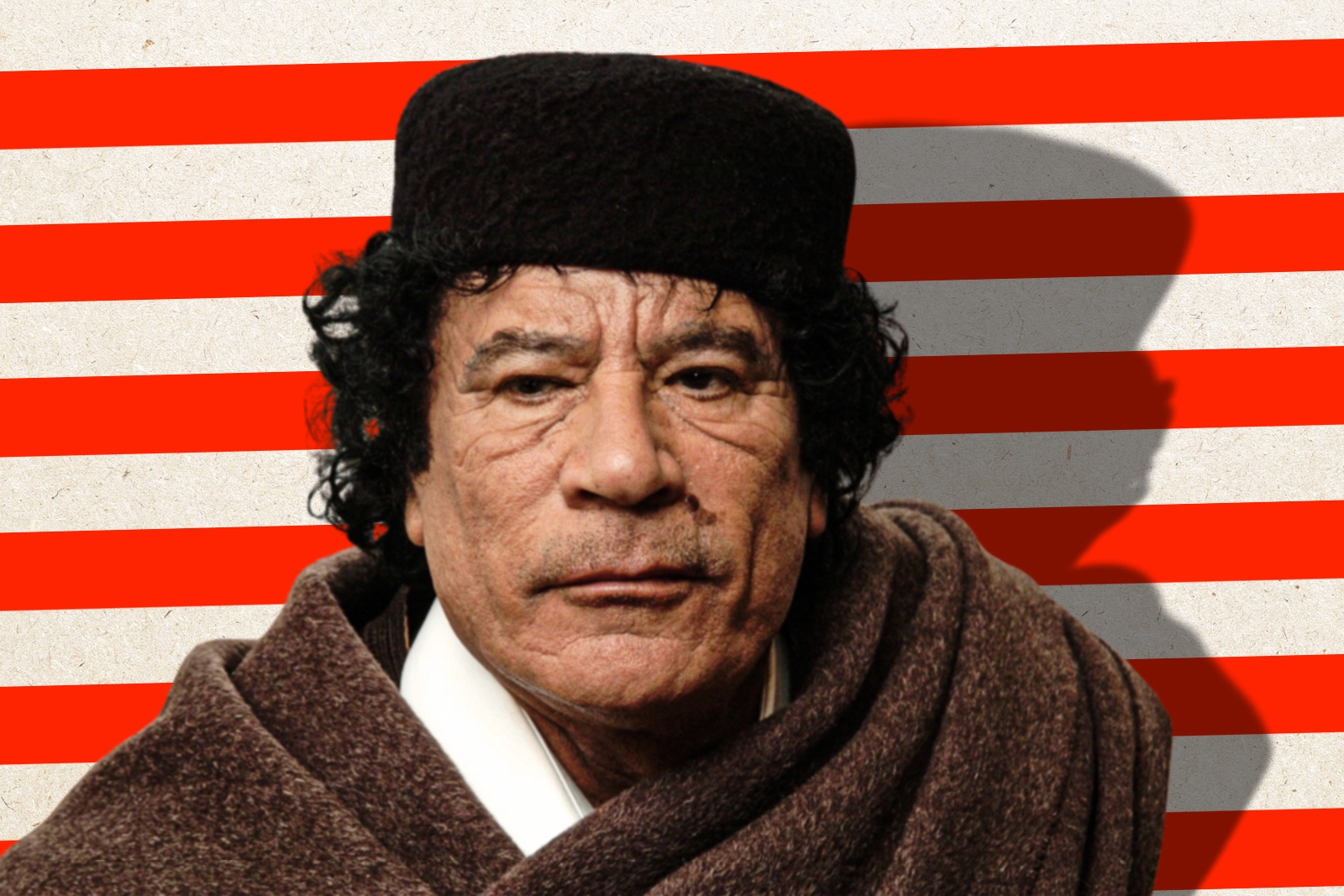

Libya, Thirteen Years After Qaddafi: Growth, Chaos, or Stalemate?

October 2024 marks thirteen years since the fall of Muammar Qaddafi, the controversial strongman who ruled Libya for over four decades. His violent fall in 2011 was heralded by many as the dawn of a brighter, democratic era.

Yet more than a decade later, Libya remains mired in uncertainty, civil strife, and a paralyzing power vacuum. The nation is fractured between two rival governments: the Tripoli-based Government of National Unity (GNU) in the west and a competing administration backed by the Libyan National Army (LNA) in the east. Thirteen years on, Libya is still struggling to navigate the wreckage of dictatorship, revolution, and relentless international meddling.

Foreign powers, drawn by Libya’s vast oil reserves, have turned the country into a geopolitical chessboard. External interests—often at odds with one another—frequently overshadow the needs of Libyans themselves. Despite being rich in natural resources, ordinary citizens face an unforgiving economic landscape marked by soaring prices, a weakened currency, and restricted access to cash. “Libyan wealth is not translating into equitable distribution of resources, access to services and opportunities for all people, particularly youth and women,” said Stephanie Koury, Deputy Special Representative for Political Affairs with the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL).

The post-Qaddafi era has delivered a grim mix of hardship, recurring conflict, and economic fragility. Healthcare, education, and electricity services remain erratic at best, forcing many to grapple with daily insecurity in a country still flush with oil wealth. The energy sector, historically the backbone of Libya’s economy, continues to dominate public life.

“The prevailing powers today are in the hands of those with economic and military power, which puts fear in others,” Qaddafi once warned, in a moment of global critique. “They can make you starve. They can close the doors for your exports of raw materials such as coffee or oil.” His words, aimed at global inequities, resonate in today’s Libya—where wealth and weaponry are tightly entwined.

Libya holds Africa’s largest proven oil reserves. Under Qaddafi, these reserves funded ambitious infrastructure projects, entrenched public subsidies, and cemented elite loyalty. By the early 2000s, production had reached 1.65 million barrels per day (bpd) of high-quality crude, up from 1.4 million bpd in 2000. With approximately 48 billion barrels in proven reserves, Libya’s oil remains a vital pillar of its economy, accounting for more than 95 percent of export earnings and over half of GDP.

Yet Qaddafi’s centralization of the oil sector also sowed the seeds of dysfunction. After his ouster, the same oil fields became contested assets. Both the GNU and the LNA have jostled for control, leading to repeated shutdowns of terminals and pipelines—costly interruptions that starve the state of revenue and deepen Libya’s fiscal woes. Despite new actors and institutions, the state’s dependence on oil mirrors past patterns, and its economy remains dangerously undiversified.

Oil is no longer just an economic lifeline; it’s a political fault line. The competing claims to oil revenues have intensified rivalries and prolonged instability. Qaddafi once remarked, “Libya lived for 5000 years without oil, and it is ready to live another 5000 years without it.” Today, that statement reads less like defiance and more like an uneasy warning: an oil-rich state without political cohesion cannot bank on its black gold to ensure national stability.

Libya’s current economic indicators underscore its deep malaise. Unemployment hovers around 18.74%, disproportionately affecting the youth. Inflation has steadily eroded the purchasing power of the Libyan dinar. Years of civil war have displaced hundreds of thousands, left hospitals in ruins, shuttered schools, and obliterated infrastructure. In many regions, access to clean water, electricity, and basic food production is inconsistent, particularly in zones hardest hit by fighting.

And yet, not all is bleak. In recent years, there have been glimmers of progress—modest gains in grassroots peacebuilding, tentative ceasefires, and increased international engagement. But these improvements are far from transformative. The legacy of chaos still casts a long shadow.

Thirteen years after Qaddafi’s fall, Libya finds itself suspended between the ghosts of its past and the uncertainty of its future. The revolution that toppled a dictator has yet to produce a stable, inclusive state. Growth, chaos, or stalemate? For many Libyans, the answer still feels maddeningly out of reach.