The Limits of Japan’s Soft Power

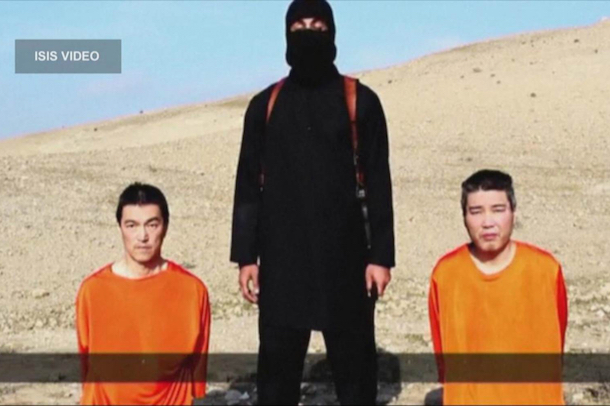

The brutal slaying of the two Japanese hostages by the Islamic State (Daesh) is a reminder, if one were needed, that the group remains impervious to universal condemnation of its methods, but also that Japan’s ability to influence the group’s actions is as limited as that of any other nation. Japan’s recent pledge of another $2.5 billion in aid to Middle Eastern countries — including $200 million in non-lethal assistance to provide some relief to countries impacted by the rise of Daesh in Iraq and Syria – may succeed in enhancing its profile in the region, but not its ability to impact the course of events.

Japan’s inability to project its power militarily as a result of restrictions in its post-War constitution continues to prevent the country from having a more meaningful role in global affairs. Apart from its immediate neighborhood, nowhere else is this more apparent than in the Middle East.

Japan is resource-poor and a leading importer of natural gas and oil, so Japanese-Middle Eastern relations have historically revolved around that dynamic. Despite the absence of cultural, historical or religious bonds, Japan and the Middle East have become important geostrategic partners.

Tokyo’s Middle Eastern foreign policy, which has been traditionally passive, has recently shifted toward a more activist role with the objective of protecting Japan’s energy interests in the region. Given that the country imports more than 80 percent of its crude oil from the Gulf Cooperation Council and Iran, stability in the Middle East is of great interest and concern to Japan.

While the Japanese military is prohibited by its post-war constitution from engaging in offensive activities, the Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF) have been deployed to the Middle East on numerous occasions in other capacities, such as humanitarian and peacekeeping missions. For example, the JSDF were deployed to the Persian Gulf in 1991 to conduct minesweeping operations in the aftermath of the Gulf War (which marked the first time that Tokyo deployed its armed forces overseas since World War II).

Between 1996 and 2012 Japan also sent peacekeeping troops to the Golan Heights and the JSDF were deployed to Iraq to aid in reconstruction efforts. In 2006, Japan initiated the Corridor of Peace and Prosperity, aimed at bringing about reconciliation between the Israelis and Palestinians. Agreements between Japan and Saudi Arabia concerning cultural exchanges and technical assistance have also factored into Japan’s ‘soft power’ campaigns in the region.

In addition to carrying out humanitarian or peacekeeping missions, Tokyo has proven increasingly interested in utilizing its military to secure Japan’s vital energy interests. In 2011 Japan committed to establishing a military base in Djibouti to assist U.S.-led anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. And in 2012, Prime Minister Noda spoke before the Diet about Japan’s need to deploy the JSDF to the Strait of Hormuz to conduct minesweeping and escort operations in the event of the Strait’s closure.

This shift is indicative of Tokyo’s increasing propensity to use ‘hard power’ to help ensure greater Middle Eastern stability. If war were to break out in the Persian Gulf, the Japanese Government would be compelled to take aggressive measures to defend its energy lifeline. The Abe government has similarly been hawkish on the expansion of the Japanese military, and seeks the gradual remilitarization of Japan.

Although it is an important U.S. ally, Japan holds some unique cards in the Middle East, maintaining cooperative ties with both Israel and Iran, for example, while remaining neutral vis-à-vis the conflict in Syria. As the top export partner for Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, number two for Oman, number three for Saudi Arabia, and number five for Iran, Japan wields considerable economic influence throughout the region.

So while it may not be widely recognized as such, Japan is an influential background actor in the Middle East. The country has no historical ‘baggage’ in the region, and the Japanese are respected on the ‘Arab Street.’ Japan is determined to be a force for peace and stability in the war-torn Middle East, yet until and unless its constitution is changed to permit the country to project its power in a meaningful manner militarily, its ability to influence events in other regions of the world will remain limited.

This article was originally posted in The Huffington Post.