The Long-Game: The El Mozote Massacre and Why Washington Swept it Under the Rug

“This is something one should talk about in another time, in another country.”- Mayor of Jocoaitique

On January 31st, 1982, Todd Greentree, an embassy officer, and Maj. John McKay, the assistant defense attaché, transmitted a cable from the American Embassy at San Salvador to the Department of State in Washington, D.C. The six-page long report, which was the product of a poorly executed investigation, failed to capture the truth about the El Mozote massacre. Officially transmitted under the name of Ambassador Deane R. Hinton, the cable sustained the Reagan administration’s foreign policy agenda in El Salvador.

On December 11th, 1981, the U.S.-backed and trained Atlacatl Battalion, led by Lt. Col. Monterrosa, ransacked the small town of El Mozote, which is located in the department of Morazán in Northeast El Salvador. The “death squad” indiscriminately slaughtered every member of the village, raped the young girls, and set fire to their homes. Rufina Amayo was the sole survivor of the El Mozote Massacre. As she waited helplessly in refuge surrounded by a heap of thick brush, Amayo listened helplessly for hours as her childrens’ screams penetrated the air like a bullet. She lay boca abajo (face down) in a hole she dug herself for cover, and she could hear the soldiers gleefully celebrating the fruits of their violent labor.

The village of El Mozote was home to jornaleros (day laborers) and campesinos (land peasants), 794 of whom were murdered by the Salvadoran government. The existence of a massacre, though widely contested at the time, is no longer up for debate. Though the memories that could illuminate the exact truth about what happened during Operación Rescate (Operation Rescue) are asleep forever, there is no more denying that the massacre did take place; it has been thoroughly documented and studied. So why, then, did the administration’s Embassy report downplay the events of December 11th? Why did they try to discredit the two reporters who traveled to El Salvador to document the wreckage and bring the story back to the United States? Why did the Embassy cable conclude that “…it is not possible to prove or disprove excesses of violence against the civilian population of El Mozote,” and incorrectly label the massacre a “combat” or “fight,” and place the ultimate blame not on the government but on the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), i.e. the forces working against Reagan’s agenda in South America? The simple, and most obvious, answer to these questions is that Reagan was an unwavering proponent of obstructing the spread of communism in the Western Hemisphere. This answer is too broad and excuses the often overpowering foreign policy in Latin America as a Cold War byproduct, not the decision-making of a President.

The Reagan administration’s decision to conceal such a massive human rights violation while concomitantly and paradoxically boosting support for the Salvadoran government by underscoring their improvements in human rights is all a matter of legitimacy. President Reagan’s strategy was to uphold the credibility of the Salvadoran government while simultaneously tarnishing the legitimacy of the FMLN insurgents. Denying, or at least downgrading, the El Mozote Massacre to a skirmish accomplished both of these goals.

A Civil War in El Salvador

A civil war that claimed the lives of nearly 75,000 in El Salvador erupted after the government opened fire on a group of anti-coup protestors in 1979. Almost a year later, in October of 1980, a coalition of five left-wing guerrilla groups, assisted by Cuba and the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, joined forces to form the FMLN. This insurgent uprising was in large part a response to the government-sanctioned violence and the military’s selective protection for the wealthy elite who sought to maintain socio-economic inequalities in El Salvador. The FMLN did their cause no favors by accruing a rap sheet that included assassinations, bombings, kidnapping Salvadoran elites for ransom, and in 1981, assuming control over large sections of Morazán and Chalatenango. In hindsight, this is likely what made El Mozote a target for the Atlacatl Battalion. Yet, most of the violence during the civil war was committed by the Revolutionary Government Junta, headed by José Napoleón Duarte, that established control of El Salvador after the 1979 coup that ousted then-President General Carlos Humberto Romero.

“The immediate goal of the Salvadoran army and security forces—and of the United States in 1980, was to prevent a takeover by the leftist-led guerrillas and their allied political organizations.” It was not the violence that pit the Reagan administration against the FMLN, but its socialist ideology. As communism inched its way closer and closer to the United States, President Reagan assumed a fully offensive position to hinder its progress. Despite the Salvadoran government’s abysmal human rights record, the Reagan administration and Congress spent billions of dollars to help the Salvadoran government counter the spread and influence of the leftist FMLN.

Certification to Counter the FMLN

El Salvador had experienced escalating levels of violence and instability during President Humberto Romero’s time in office. Even though human rights in El Salvador was a topic of discussion in the United States, President Jimmy Carter more or less left El Salvador on its own, only offering a sprinkling of aid here and there. It was not until the FMLN ascended into being that the United States’ interest peaked in El Salvador. The birth of the socialist FMLN meant to the new Reagan administration that the threat of communism was gaining ground in the Western Hemisphere. Reagan asked Congress to increase the amount of aid sent to the Salvadoran government to counteract the growing threat. In response, Congress granted the request but with the condition that the President certify every six months that human rights conditions in El Salvador were improving.

The administration increased its aid to the Salvadoran government leveraging the argument that the “…alternative to continued U.S. assistance ‘will be a communist Central America with additional communist military bases on the mainland of this hemisphere…’” Thomas Enders, the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, said during testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee that “Terminating aid would be a ‘massive blow’ to the government [El Salvador’s government], would lead to even more bloodshed, and would ‘probably’ result in an insurgent victory.” The Reagan administration perceived a direct link between U.S. assistance and the spread of communism in El Salvador, the rest of Latin America, and as a direct threat to United States security.

The first certification was presented on January 28th, 1982, one day after New York Times reporter Raymond Bonner and Washington Post reporter Alma Guillermoprieto broke the news of a massacre in El Salvador. Debate and discussion carried on for a few weeks but eventually receded after the Embassy’s official investigation produced an inconclusive verdict. The report laid ultimate culpability on the FMLN, and it claimed that “civilians remaining in any part of the canton could have been subject to injury as a result of the combat” [italicized for emphasis]. Further, the report suggested that there was not “…any evidence that those who remained attempted to leave.” The validity of this investigation was called into question after a post-hoc analysis revealed that Greentree and McKay never actually visited El Mozote. In fact, it was the Salvadoran military who briefed them and accompanied them on a helicopter ride over the village. There was reason to believe that the FMLN would act hostile towards them had they tried to enter the village, but this, along with the limited scope of the investigation, was not discussed in the official report.

The second certification was transmitted on July 27, 1982, and in it the Reagan administration concluded “…that the Government of El Salvador is making a concerted and significant effort to comply with internationally recognized human rights to fix their problems and that “…military leaders continue to work toward curbing human and civil rights abuses…” This assertion could have easily been challenged had the reports and evidence of a massacre in El Mozote been accepted by the administration. The certification makes no mention of a massacre, although it did acknowledge the persistence of “frequent violations of basic human rights committed by…the Government’s military and security forces.”

The administration was of the mind that, “[a] political resolution is the only solution for El Salvador.” These certifications were a political tool meant to boost the legitimacy of the Salvadoran government. The aid, inextricably linked to the preservation of democracy and demise of the leftist agenda, was the key to ensuring a positive outcome in the elections that were scheduled to take place four months after the massacre at El Mozote.

The Long Game

Reagan requested a National Intelligence Estimate be conducted about the upcoming Salvadoran elections. The intelligence community concluded that the elections were likely to take place as planned, but with possible disruptions from the guerillas. The NIE said that “The guerillas will try to disrupt the election with an escalating series of military assaults and assassinations.” The NIE predicted that the Christian Democratic Party would secure a majority of seats and that this outcome would “…validate the Salvadoran military’s efforts to work with progressive civilians.” The report goes on to say that “Legitimizing elections would strengthen US interest and bolster democratic forces in Central America and elsewhere in the region…”

After the coup in 1979, Jose Napoleon Duarte returned from exile as the provisional president of the new junta government. One of the junta’s first and more tenacious priorities was to plan a Constituent Assembly election. As the civil war raged on in the background, the elections were set to take place on March 28th, 1982. The provisional-president-turned-elected-President in 1984 campaigned on a series of talking points that promoted private sector growth, agrarian reform, economic improvement, judicial restoration, and the assurance of open dialogue with the guerillas. The outcome of the election was well-received from both inside and outside the government. Duarte’s Christian Democratic Party won 24 of the 60 seats, and the remainder of the seats were won by various parties of moderate political persuasions. The next task on their agenda was to plan for Presidential elections in 1984.

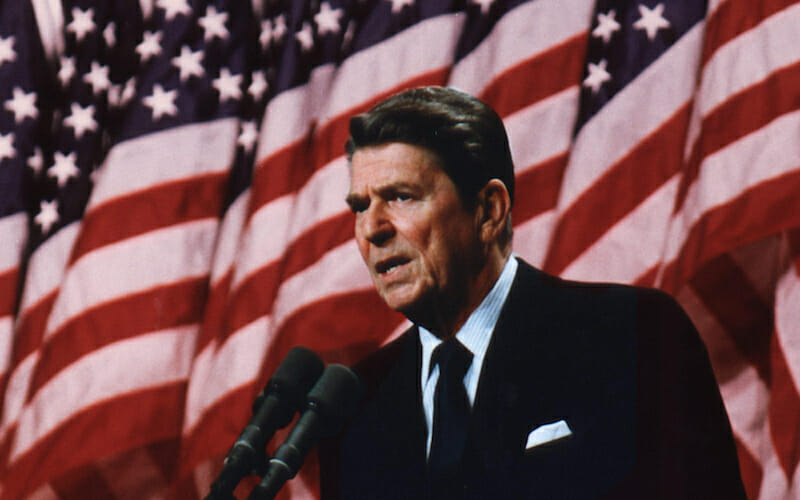

Reagan had expressed public concern about the outcome of elections in El Salvador. For example, during a speech at the Annual Meeting of the National Association of Manufacturers, Reagan referenced the 1982 elections and discussed his expectations for the 1984 Presidential election that was being organized by the newly elected Constituent Assembly. Reagan drew many parallels between the Salvadoran government and U.S. national security. “The nations of Central America are among our nearest neighbors. El Salvador, for example, is nearer to Texas than Texas is to Massachusetts. Central America is simply too close, and the strategic stakes are too high, for us to ignore the danger of governments seizing power there with ideological and military ties to the Soviet Union.” He continued to say that, “[t]housands of people have already died and, unless the conflict is ended democratically, millions more could be affected throughout the hemisphere.” At the core of U.S. interests, even broader issues are at stake. The administration hoped to shield Costa Rica, whose durable democracy at the time faced severe economic problems, from its own leftist revolution. They were also concerned with rolling back Cuban influence and containing the growing military strength of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. There was a real fear that a domino effect would begin in El Salvador and cascade through Central America. “If El Salvador does go to the insurgents,” one administration official said, “Nicaragua will be heartened, and we can look to the fall of Guatemala in the not-too-distant future.”

Reagan never formally proclaimed favor over one party or another, or one candidate or another. His priority was focused on the growth and popular emergence of the FMLN, the antidote of which was a legitimate election overseen by a legitimate government. While the extent to which U.S. assistance helped to secure a democratic victory in El Salvador would be impossible to calculate, it sends the obvious message that the Reagan administration, for better or worse, considered this a worthy-enough value to ignore the crimes committed by the Salvadoran government. The line that must be followed to this conclusion is easily traced. The El Mozote massacre, had it been accepted as reality, would have made it politically impossible for Reagan to certify the Salvadoran government’s human rights improvements. The certification was necessary (barring a second Iran-Contra-like arrangement) for the U.S. to send assistance to the Salvadoran government, which it desperately needed to bolster its legitimacy against the FMLN and secure a victory in the 1982 elections.

It would seem that the administration’s decisions were not grounded so much in reality, but in the ideological preservation of an idea. The idea that democracy, no matter how brutal it could behave, was better than any other alternative. This world of black and white served an injustice to those who lost their lives in El Mozote on December 11th, 1981.