Modi Boards the Trump Train

When describing the U.S.-India relationship at his mid-December farewell ceremony, Indian Ambassador to the U.S., Natvej Singh Sarna, said: “We have found a huge amount of understanding…for our strategic autonomy.” Past leaders of the world’s two largest democracies have shown an understanding, albeit trying, of strategic autonomy’s criticality in India’s foreign policy. However, since the beginning of U.S. President Donald Trump’s term, India and the U.S. have taken a new approach to this guiding Indian foreign policy tenet. Trump and his administration’s unrealistic compliance requirements linked to the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) and India Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s lack of significant pushback not only diminish the South Asian giant’s long-standing priorities but also weaken the U.S.-India strategic partnership vis-à-vis China.

After nearly one hundred years of British rule, the first prime minister of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru, ushered in a neutral Cold War foreign policy of supporting neither the Soviet Union nor the U.S. This non-alignment enabled India to make decisions without Soviet or American influence. Throughout the Cold War, the policy continued to the scorn of the U.S. which insisted on New Delhi’s obedience to Washington’s demands.

In the twenty-first century, India’s economic liberalization and a U.S.-India nuclear deal led to a substantial improvement in the U.S-India partnership under President George W. Bush. The Obama administration increased focus on U.S.-China cooperation, but the U.S.-India partnership continued to grow.

Today, Trump, Modi, and China President Xi Jinping converge at a momentous yet uncertain time in geopolitics. India’s multilateral ties, economic strength, sizable military, booming population, and geostrategic position can tip the scales in favor of a U.S.-led entente countering a belligerent China. But the foreign policy that has provided India such leverage in Asia economically, diplomatically, and militarily is now at risk.

On August 2, 2017, Trump signed into law CAATSA which places further sanctions on North Korea, Iran, and Russia, in addition to secondary sanctions on those who undertake certain transactions with those nations. Unsurprisingly, India has substantial connections with both Iran and Russia. Iran was India’s second largest oil supplier, and Russia supplies 60% of India’s arms imports. Sanction sights centered on India. However, CAATSA provides sanctions waivers to be used at the president’s discretion.

On the eve of Iranian oil sanction re-imposition, Trump granted waivers to India and seven other countries (including China) after lobbying by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis. As expected, Washington attached steep requirements that would undermine the deep-seated India-Iran energy partnership: purchase of Iranian oil must be substantially reduced and aimed at “zeroing”; and purchase of Iranian oil must be through a special rupee payment system. New Delhi agreed.

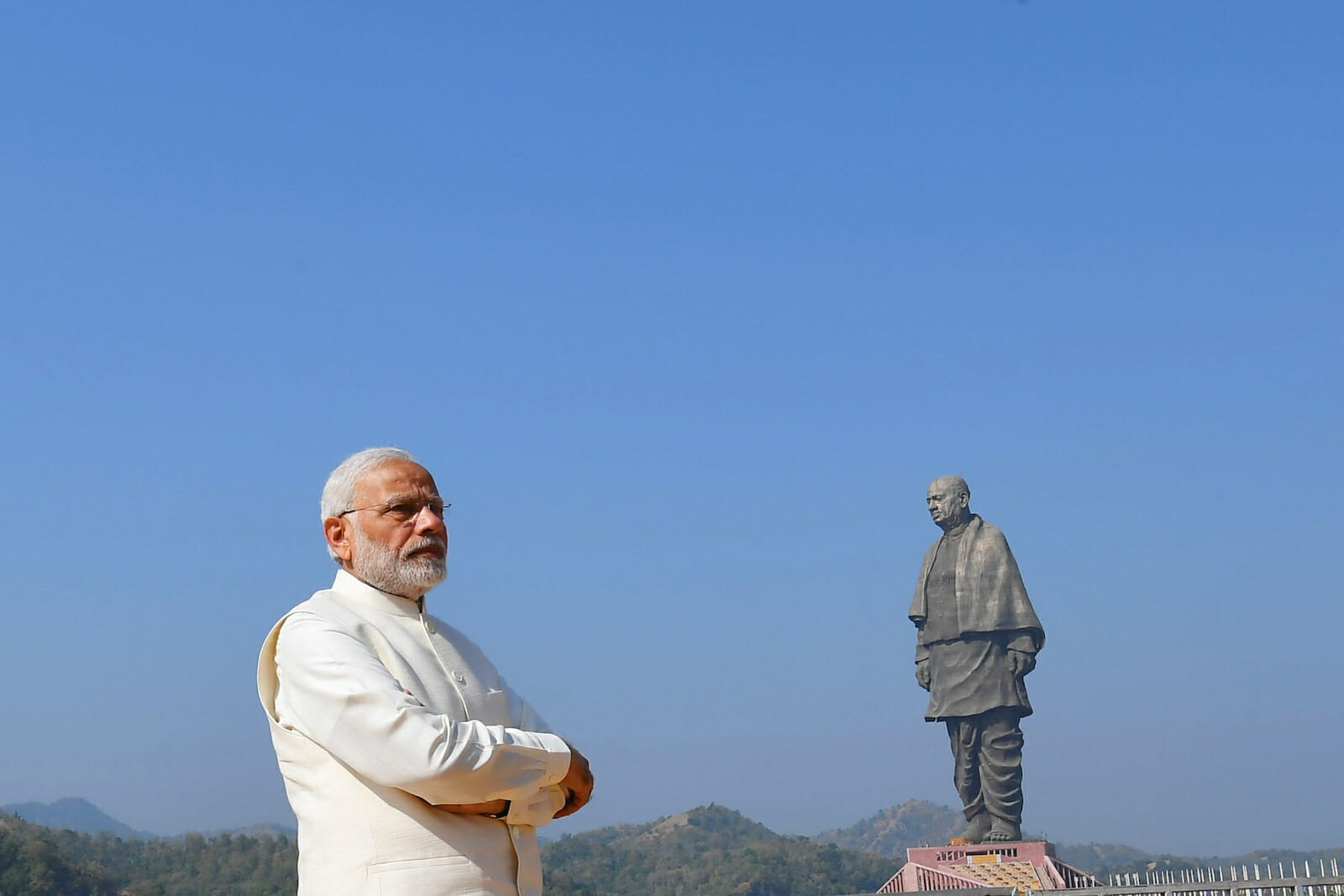

By allowing the subversion of the historical India-Iran relationship in favor of appeasing Trump – whose very own Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy requires India’s partnership – Modi revealed a major change to seventy years of Indian geopolitical strategy. Perhaps Modi’s longtime attachment to the U.S. may be the source of his overt U.S. bend. In a July 2018 op-ed, Bharat Karnad, current research professor at the Centre for Policy Research and former member of India’s National Security Council Advisory Board, said that “Modi’s [U.S.] tilt is undergirded by his personal regard and admiration for America shored up during his travels in that country in the 1980s on his own, as a BJP functionary, and as part of the U.S. State Department hosted tours for ‘young leaders.” Modi’s esteem for the U.S. appears to have translated into acceptance of obstinate U.S. demands.

While a decline in the India-Iran relationship appears relatively minor, a positive India-Iran relationship underlies a greater Indian strategy to gain market access and influence in Afghanistan and China-dominated Central Asia. Should Modi weather general elections in April and May 2019, Trump will likely attempt to coerce him on trade which may result in further Indian withdrawal from Asia. Where India retracts in Asia, China will undoubtedly fill the void. The resignation of Secretary Mattis, who urged Trump to issue a waiver for the Indian-owned Iranian Chabahar port and an expected waiver for India’s $5 billion purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems, also ensures the U.S.-India relationship is set for a wild ride in 2019. If Trump and Modi want to counter an emboldened Xi-led China, strategic autonomy – not the coattails of American power – is an essential belonging on their journey. Unfortunately, it looks as though Modi has already boarded the Trump train. And strategic autonomy was left behind.