Books

‘The Monuments Men’ Reviews: Book and Film

Artistic license can take many forms when applied to historical narrative, and it is my hope that in reading my reviews of the book, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, and the film adaptation, The Monuments Men, the reader will get a full picture of the heroic men and women who rescued European art from the Nazis – the Monuments Men, and how they have been portrayed in print and on the silver screen.

Book Review

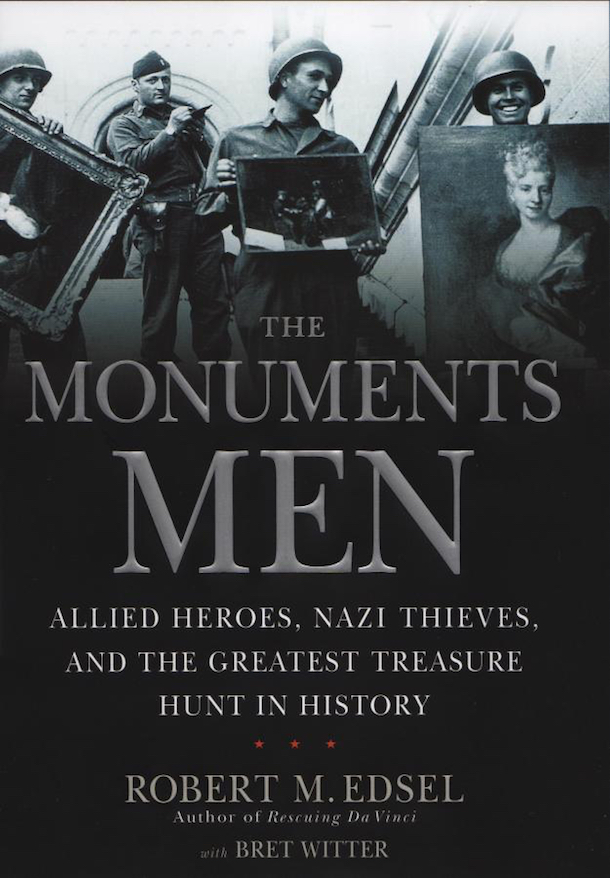

The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel, with Bret Witter, takes the reader into the World War II war theater through the stories of ten of the brave men and women, the Monuments Men, who rescued art that had been stolen by the Nazis in Europe. The book is chronological, and the author cleverly weaves in historical anecdotes to show the importance of the preservation of art and culture during times of mass destruction and genocide.

Edsel’s powerful, moving narrative emphasizes the role of humanity in protecting the artifacts of antiquity, and stresses the non-monetary value of those artifacts which represent human possibility, creativity, and intellectual achievement.

The storyline allows the reader to travel with the Monuments Men on their journey to the front lines on a treasure hunt through Europe to find, identify, and return stolen art.

The book is divided into five sections, and it features one woman, Rose Valland, and nine men: Ronald Balfour, Harry Ettlinger, Walker Hancock, Walter “Hutch” Huchthausen, Jacques Jaujard, Lincoln Kirstein, Robert Posey, James Rorimer, and George Stout.

Section I: The Mission

Edsel begins in Karlsruhe, Germany. Through the lens of life in Karlsruhe, he describes the history of the Jews in Europe leading up to 1938. Jews were gradually disenfranchised, and when Hitler came to power many fled to the United States, including the family of Monuments Man Harry Ettlinger. Edsel juxtaposes this with the evolution of Adolf Hitler’s obsession with art. This storytelling device makes the plight of the Jews personal, while simultaneously giving historical context.

Before reading the book, I did not know that Hitler had been an aspiring artist. Rejected from art school, Hitler still believed he was meant to create great art. In 1938, while visiting Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, he saw Rome and Florence and his vision changed: “He was not destined to create, but to remake. To purge, and then rebuild. To make an empire out of Germany, the greatest the world had ever seen…Berlin would be his Rome, but a true artist-emperor needed a Florence.”

Hitler drew up plans to make the Führermuseum in Linz, Austria (his hometown, his Florence), and fill it with art taken from countries he would conquer. As Hitler and the Nazis moved across Europe, occupying Paris and bombing London, the American museum community began preparing for war. It is here that the reader is introduced to George Stout, head of Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum’s Department of Conservation and Technical Research. Stout pioneered art conservation in the 1930s, creating scientific principles to evaluate and preserve art, and became the leader of the Monuments Men.

In 1943, General Dwight D. Eisenhower issued an executive order: “stating that important artistic and historical sites were not to be bombed.” – except when necessary to avoid sacrificing American soldiers. (pg. 46) Beginning in 1944, the Monuments Men were enlisted in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) sub commission, run by the Civil Affairs branch of the Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories (AMGOT). With a dedicated unit (MFAA) and Eisenhower’s executive order it seemed the Monuments Men’s mission was supported by the military. When they arrived in Europe, however, they found this was not the case.

Section II: Northern Europe

Upon entering the war theater in Northern Europe, the Monuments Men were able to see first hand the enormity of their mission and its challenges. More than five million cultural objects had been transported by the Nazis to the Third Reich, and it was their task to return them.

Edsel makes the two most important points in the book here: the complex nature of the Monuments Men’s task, and that they were not a unit. He uses their first group meeting on August 13, 1944, outside the ruins of Saint-Lô, France, to emphasize these points. Despite being a town of historical significance, 95 percent of Saint-Lô had been destroyed. It was a lynchpin of Allied success, giving them the high ground over the Germans. Military strategy to win the war superseded art preservation, and the Monuments Men had to complete their mission regardless. Also, though they were assigned to military units, they were alone in the field: “Theirs was a solitary task. They weren’t a unit; they were individuals with individual territories and individual goals and methods.” (pg. 87)

The Monuments Men dispersed to pursue their missions, and Edsel highlights two of the major pieces they needed to save: Michelango’s Bruges Madonna (Chapter 12), and Van Eyck’s Mystic Lamb, known as the “Ghent Altarpiece” (Chapter 14). These were prized by Hitler and held in his private collection.

We are also introduced to the key European players in the story: Jacques Juajard, director of the French National Museum, and Rose Valland, secretary at the Jeu de Paume museum. Jaujard saved art housed in French museums, evacuating it to safe houses in the French countryside before the occupation. He aided the Monuments Men by helping to identify key private art collections the Nazis had confiscated. Valland secretly kept records of the art that was stolen and where it was being stored. By this point, Edsel has given the reader a solid grounding in the story. We are aware of the historical context, challenges, and significance of their mission. And then we enter Germany.

Section III: Germany

After the Allies used the bridge at Remagen to cross the Rhine and enter Germany, Hitler had four soldiers executed (March 18, 1945), and issued his Nero’s Decree (March 19, 1945). In it, Hitler ordered that German infrastructures – bridges, railroads, and factories – be destroyed to impede Allied advancement. The Nazis would raze everything in their wake to hinder the enemy. With the pressure of the Nero’s Decree driving them to complete their mission before Germany’s infrastructure is destroyed, the story takes on new intensity. The Monuments Men had identified which key art pieces they needed to rescue and they knew where to find them, it was a matter of getting there quickly and safely.

Valland had given the location of the repositories to James Rorimer, including the location of the French private collections – Neuschwanstein castle in Germany. Meanwhile, Robert Posey and Lincoln Kirstein came across an art expert who had worked in Paris. He told them that Hitler’s private collection, including the Bruges Madonna and Ghent Altarpiece, was in a salt mine in Altaussee, Austria. Through a stroke of luck American soldiers uncovered Nazi gold in a salt mine in Merkers, and discovered that it was an art repository as well. On April 8, 1945, Posey and Kirstein arrived at the mine and got to work identifying and categorizing the art. Posey contacted Stout, who came to help. Although the discovery of gold and treasure at Merkers made international headlines, there were still two important repositories to be recovered: Neuschwanstein and Altaussee.

Section IV: The Void

As the war came to a close, Germany became a “void” where the Allies were advancing, the Nazi government was collapsing, and no real authority existed. Edsel paints the picture of an investigative haze, filled with doubt and lacking information. It was in this chaos that the Monuments Men operated, trying to track down stolen art by talking with villagers and surrendering German soldiers. Some cooperated, while others did not. War weary and distrustful, they feared unforeseen repercussions. On May 4, 1945, Rorimer finally reached Neuschwanstein. The art was untouched, and the Nazi records and catalogues of the art were still in their filing cabinets. Then on May 7, 1945, the Germans unconditionally surrendered. The Allies had won the war.

Section V: The Aftermath

Adolf Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. It is clear in his last will and testament that he did not want the art the Nazis had confiscated destroyed, particularly his private collection. However, his actions and words leading up to that point, from Mein Kampf (1925) to his Nero’s Decree (1945), were in direct contrast to the ideals of art conservation and the preservation of humanity and its achievements. Edsel explains on page 373: “…his orders over the course of many years – including the burning of books; the destruction of ‘degenerate’ art; the pillaging of personal property; the arrest, detention, and systematic annihilation of millions of human beings; and the willful and vengeful destruction of great cities – put the artwork, and everything else within the reach of any Nazis anywhere in the world, at tremendous risk.”

Despite the efforts of high level Nazis to destroy the Altaussee mine, it was saved by the mine director, mine foreman, and the miners, who risked their lives by defying these orders in the name of art preservation. On May 12, 1945, Posey and Kirstein arrived in Altaussee where, with Stout, they recovered the Ghent Altarpiece and Bruges Madonna.

Though their mission had come to an end, Edsel uses this last section to explore the Monuments Men’s legacy and importance after the war. Rorimer used the former Nazi Party Headquarters in Munich as a collection point for southern Germany and Austria. And after that was full, another building in Wiesbaden. Almost 350 men and women served in the MFAA, most of them after the war, and they worked until 1951 to recover and return stolen art.

The Monuments Men continued to contribute to the art world after they came home. Some notable achievements include those of Lincoln Kirstein, James Rorimer, and George Stout. Kirstein co-founded the New York City Ballet in 1948. Rorimer became the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1955 and during his tenure attendance rose from two million to six million visitors annually. Stout became the director of the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, and then moved on to be the director of the Isabella Stewart Gerdner Museum in Boston. He is still considered a pioneer and giant in the world of art conservation.

Since World War II, there has been no unit equivalent to the MFAA in the U.S. military. The Monuments Men’s contribution to the world is one that should be duplicated, for their mission was not purely one of art conservation, but the protection of key artifacts that symbolized humanity’s potential for creation. The obstacles the Allies faced in defeating the Nazis were not just ones of geographic and political sovereignty, but also the protection of cultures, and their potential to evolve, for generations to come. I highly recommend Robert M. Edsel’s The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History for those in need of inspiration. Its message is universal and transcendent.

Film Review

George Clooney directed, co-wrote, and stars in the film The Monuments Men. Therefore, much of the responsibility to make an accurate and engaging film rests on his shoulders. The result is disappointing. The book on which it is loosely based, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, tells the rich and exciting story of the men and women who rescued European art from the Nazis in World War II. It could have made an excellent film. Instead, it felt like Clooney was trying to make another Ocean’s film: a group of guys out on a heist. His attempt fell flat.

The film opens with Mr. Clooney, who stars as George Stokes, based on George Stout, addressing President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the importance of preserving art, which is being looted and destroyed in Europe. Stout is portrayed in the book as stoic, focused and driven. Stokes is a hokey caricature of Gary Cooper (star of the iconic 1941 war film “Sergeant York”), relying on one-liners and sappy speeches. The supporting cast is star studded: Matt Damon plays James Granger, based on James Rorimer. Bob Balaban plays Preston Savitz, based on Lincoln Kirstein. And Cate Blanchett plays Claire Simone, based on Rose Valland. A talented bunch with many Oscar nods to their name. Unfortunately their talent can’t save a mediocre script with limited plot development, and their characters come across as cartoonish.

There are several historical inaccuracies: the way the Monuments Men met, the methods and order in which the art is recovered, and how they carried out their mission, all vary from the book. All that could be allowed, perhaps, if the film had a cohesive storyline, but it lacks focus – jumping from one caper to the next – and relies on the audience’s knee-jerk negative emotional response to Nazis and swastikas; interspersed with sappy music, letters written home, and melodramatic death scenes.

The most upsetting fabrication is that the film, as opposed to the book, portrays the Monuments Men operating as a unit, which undercuts their true heroism. Theirs was a solitary mission and as such, with limited resources, made it all the more difficult and dangerous. There weren’t enough Monuments Men to have them all meet up and work on one project; travel together, recover art together, and go on adventures through Europe together. At most they would sometimes work in pairs; and perhaps George Stout, their leader, would be solicited for his expertise.

In my opinion, the true story of the Monuments Men needs no changes, and if changes are made they should be ones that add drama, and perhaps romance, to the story. The film should have adhered more closely the truth, as it was told in the book. Instead, the audience sees a fun group of guys, and one lonely French lady, who bumble through art filled adventures in World War II. The Monuments Men is a lackluster and unsatisfying watch, especially if you know the true story.