Mosques, Museums and Politics: The Fate of Hagia Sophia

When the caustic Evelyn Waugh visited the majestic sixth-century creation of Emperor Justinian, one subsequently enlarged, enriched, and encrusted by various rulers, he felt underwhelmed. “‘Agia’ will always win the day for one,” he wrote of Istanbul’s holiest of holies, Hagia Sophia, in 1930. “A more recondite snobbism is to say ‘Aya Sofia,’ but except in a very sophisticated circle, who will probably not need guidance in the matter at all, this is liable to suspicion as a mere mispronunciation.”

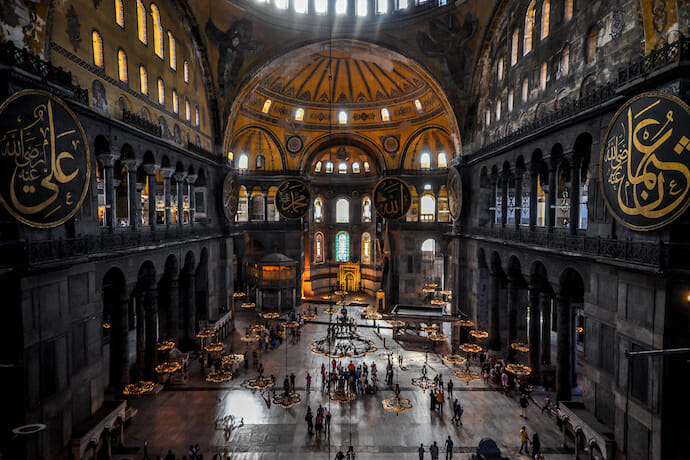

In a somewhat cool reaction, Waugh struggled to reconcile the pop mythology, at that point elevated by celebratory brochure and tourist packages, with the sight of it. “We saw Agia Sophia, a majestic shell full of vile Turkish fripperies, whose whole architectural rectitude has been fatally disturbed by the reorientation of the mihrab.”

Such snobbery could not impeach the historical pedigree of Hagia Sophia. The seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, religious edifice of the Byzantine Empire, it became a mosque once Constantinople was successfully captured by the Ottoman forces of Mehmet II in 1453, officially terminating the vestigial remains of the Eastern Roman Empire. This was a function the structure served till 1934, when the secularist ruler Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ordered its conversion to a museum. Doing so served to secularize and neutralise a site of religious jostling.

That said, the 1934 decision could hardly be seen as a mark of pure benevolence. It was a year when Turkification policies were being applied with gusto, best characterised by Settlement Law of 1934 (Law No. 2510). It was an instrument designed to resettle (or not, in some cases) populations within the state into three zones with a focus on concentrating Turkish populations in some areas, while relocating and resettling populations “whose assimilation into Turkish culture is desired.”

That same year, pogroms against Jews in Eastern Thrace also took place to resolve, in the evocatively sinister words of İbrahim Tali, inspector general of Thrace, the “Jewish problem.” The Jews, he argued, had not Turkified themselves with sufficient rigour. They were also economically advantaged while disadvantaging Muslims in lending them money at high rates of interest.

The museum status of the edifice has had its fierce detractors. The poet Necip Fazil Kisakürek described it in 1965 as “a sarcophagus in which Islam is buried.” Under the rule of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Hagia Sophia has been sporadically threatened with a change of status. In 2004, the Turkish Union of Permanent Vakifs of Historical Monuments and Environment issued a plea to the government to change the standing of the building. It was politely ignored. In 2005, the Union petitioned the country’s highest administrative court, the Council of State, to return Hagia Sophia back to its standing as a mosque. Ever persistent, that same body sought relief in the Constitutional Court, an application that was rejected in 2018.

In November 2013, deputy prime minister Bülent Arinç expressed the view that the approach of treating former mosques as museums was due for revision. He did so like a mystic, claiming that the structure was speaking to the Turkish state in mournful longing. “We look at this forlorn Hagia Sophia and pray to Allah that the days when it smiles on us are near.” Despite stirring up a fuss with the secularists and irate voices in Greece at the time, he had reason to be confident, given the abolition of the museum status of the Hagia Sophia in both İznik and Trabzon. In both cases, the General Directorate of Pious Foundations, overseen by Arinç, were active and eventually successful.

The effort to de-museum Hagia Sophia have tended to receive billowing encouragement with undesired remarks in foreign quarters about Turkish policies, past and present. Demagoguery is ever on the permanent hunt for excuses. In 2015, Pope Francis chose April to use a word illegal in Turkish law to describe the treatment by Ottoman forces of Armenians a century prior. The deportations, massacres, and rapes constituted, in an address by the Pope at a Mass in the Armenian Catholic rite at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, “the first genocide of the 20th century.” To conceal or deny “evil is like allowing a wound to keep bleeding without bandaging it.”

The remarks had their shaking effect in Ankara. Turkey’s foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu dismissed the statement, “which is far from the legal and historical reality.” It was not for religious authorities “to incite resentment and hatred with baseless allegations.” Domestically, eyes turned to the status of Hagia Sophia. The mufti of Ankara, Mefail Hızlı, saw a change as imminent. “Frankly, I believe that the pope’s remarks will only accelerate the process for Hagia Sophia to be reopened for [Muslim] worship.” That same month, the first recitation of the Quran for 85 years was made by Ali Tel, imam of the Ahmet Hamdi Akseki Mosque in Ankara.

The wheels were in motion and reached a terminus with the conclusion by the Council of State that “the settlement deed allocated it as a mosque and its use outside this character is not possible legally.” The 1934 decision ending the building’s “use as a mosque and defined it as museum did not comply with laws.” A delighted Erdoğan rushed off the decree to the state’s religious affairs directorate enabling the reopening of the structure as a mosque. The decree was celebrated by AK members in parliament.

As with many sites of religious contestation, conquest comes with grievance and hot tears of indignation. The Russian Orthodox Church, through spokesman Vladimir Legoida, expressed the view that “millions of Christians had not been heard.” The “need for extreme delicacy in this matter were ignored.” UNESCO’s World Health Committee is planning to review the status of Hagia Sophia, claiming it “regrettable that the Turkish decision was not the subject of dialog or notification beforehand.”

Erdoğan’s concerns lie elsewhere. He has had little truck with ecumenical politics and practises, battering down the secular divides within his country. His agenda is that of an up-ended Attatürk. As Soner Cagaptay of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy remarks, “Just as Attatürk ‘un-mosqued’ Hagia Sophia 86 years ago, and gave it museum status to underline his secularist revolution, Erdoğan is remaking it a mosque to underline his religious revolution.” The ancient monument of emperors and sultans promises to be a stage of much self-promotion, with the court decision coming in time for prayers to take place on July 15, the date marking the failed coup attempt.

To keep matters interesting, the Turkish president is remaining oblique on what will happen to the tourist trade. (Last year, 3.7 million ventured to the edifice.) Spokesman İbrahim Kalın has told the Turkish news agency Anadolu that, “Opening up Hagia Sophia to worship won’t keep local or foreign tourists from visiting the site.” Capitalism and finance are often near neighbours of holiness and spirituality.