Politics

Obama’s So-Called Doctrine

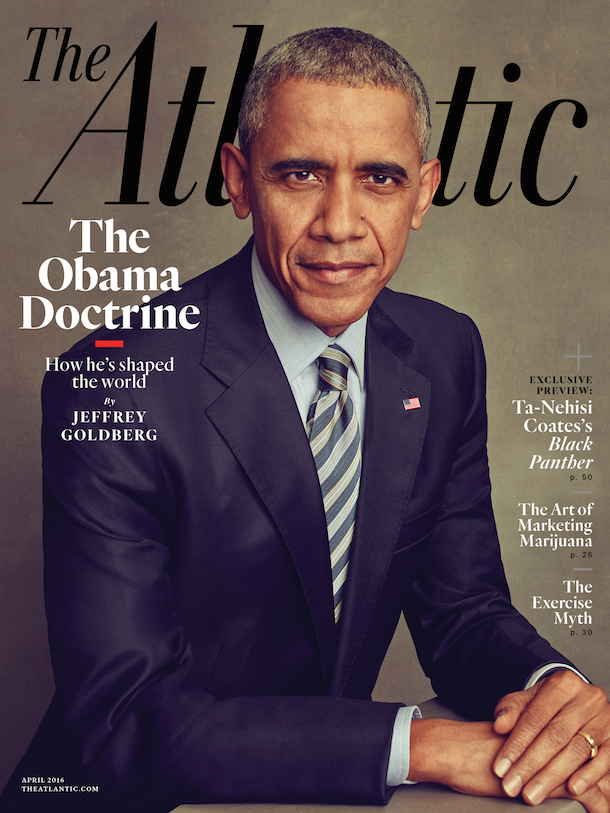

Jeffrey Goldberg’s big piece in The Atlantic is the article that everybody in Washington has been talking about. The article provides a range of insights into how U.S. President Barack Obama thinks about foreign policy and America’s role in the world. The article is worth reading in full, although some may find it difficult to get through.

At the outset of the piece we revisit Syria and look back on Obama’s red line fiasco from 2013, except Obama doesn’t see it as much of a debacle at all.

The president tells Goldberg about how proud he is of that moment. And, incredibly, then explains his decision as an act of political courage.

Here’s Goldberg’s interpretation of how Obama sees the incident: “I have come to believe that, in Obama’s mind, August 30, 2013, was his liberation day, the day he defied not only the foreign-policy establishment and its cruise-missile playbook, but also the demands of America’s frustrating, high-maintenance allies in the Middle East—countries, he complains privately to friends and advisers, that seek to exploit American ‘muscle’ for their own narrow and sectarian ends.”

“By 2013, Obama’s resentments were well developed. He resented military leaders who believed they could fix any problem if the commander in chief would simply give them what they wanted, and he resented the foreign-policy think-tank complex. A widely held sentiment inside the White House is that many of the most prominent foreign-policy think tanks in Washington are doing the bidding of their Arab and pro-Israel funders. I’ve heard one administration official refer to Massachusetts Avenue, the home of many of these think tanks, as ‘Arab-occupied territory.”’

The piece then delves into an array of topics. “My goal in our recent conversations was to see the world through Obama’s eyes, and to understand what he believes America’s role in the world should be,” writes Goldberg.

In parts of the article, Obama comes across as whiny and petulant. The president is obviously frustrated with “free riders” and wants other nations to do more to promote global peace and security. “Part of his mission as president, Obama explained, is to spur other countries to take action for themselves, rather than wait for the U.S. to lead,” notes Goldberg.

Let’s turn to Libya and the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi in 2011. Obama doesn’t see any problems with the way the initial operation was conducted, but – of course – acknowledges that things did not go well after Qaddafi was ousted. And what can be learned from what transpired in post-Qaddafi Libya?

When pondering what didn’t go so well, Obama mentions that “he had more faith in the Europeans” and criticizes both the British and French for not doing enough. The president also blames tribal divisions within Libya. There is plenty of blame to go around, it seems, as long as it’s not ascribed to the current occupant of the White House.

Israel and Saudi Arabia, longtime friends of America, are clearly not Obama’s favorite allies. (The president seems more interested in making new friends.) “His [Obama’s] frustration with the Saudis informs his analysis of Middle Eastern power politics,” writes Goldberg.

Returning to Syria, we are reminded that U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has, over the past twelve months, consistently asked Obama to do more, including bombing specific targets of the Assad regime. We also (unsurprisingly) learn that the president “seems to have grown impatient with his lobbying.”

Throughout the interview, Obama comes across as arrogant, aloof and very dismissive of people with whom he doesn’t agree. Parts of the piece read like something that one might hear from an ex-president, as opposed to someone still holding elected office.

It will take time to fully understand the consequences of some of Obama’s biggest foreign-policy moves, such as the Iranian nuclear accord, the U.S.-Cuba rapprochement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Maybe history will judge him kindly. Maybe we’ll look back on the Iranian nuclear deal as a moment of bold, brilliant diplomacy. Maybe Obama will be remembered for groundbreaking work on climate change. Maybe the president’s minimalist approach to global affairs will be revered in coming decades. Maybe we all just need a bit more time to fully understand how farsighted the president’s foreign policy actually is.

That’s a lot of maybes.