Politics

On Timing and Political Leadership

“Men at some time are masters of their fates.” – Julius Caesar

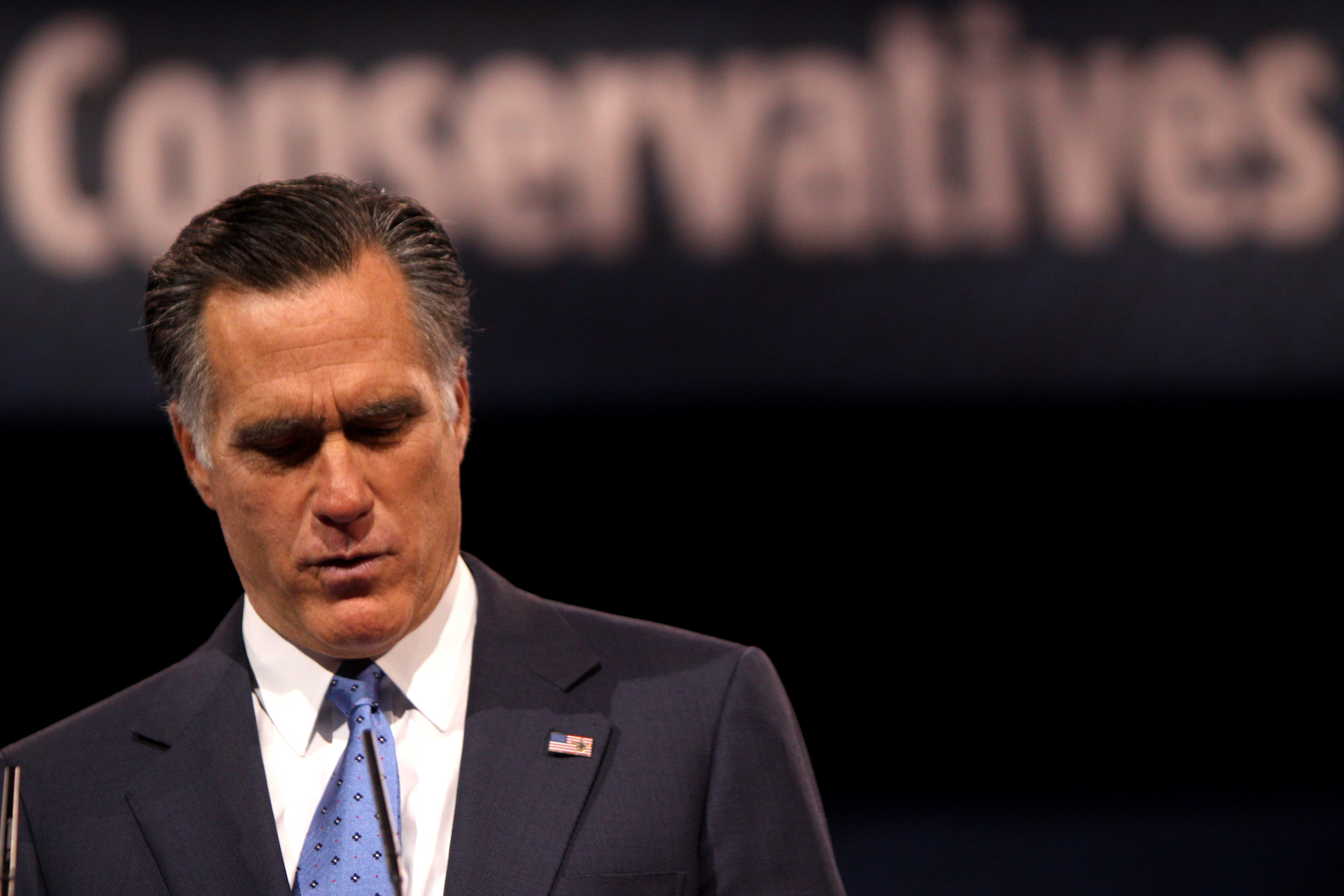

Amid the worsening economic picture, political leaders across the globe are under attack for their lack of leadership and failure to inspire confidence in their constituencies in the face of mounting global problems. President Obama especially has been criticized as too aloof and lacking direction, particularly from rightwing commentators. During the recent CNN Tea Party debate, Mitt Romney stated that, if elected president, he would have a bust of Winston Churchill in the White House. The message Mitt Romney attempted to send was clear: strong political leadership could overcome even the most severe political crisis, and that he, Romney, would follow in Churchill’s footsteps. We often forget, however, that it not only takes charisma and extraordinary ability to inspire greatness in a leader, but more importantly, the right timing.

References to Winston Churchill are nothing new. Every U.S. President post-1945 is bound to be compared to him. Churchill, however, did not do very well during peace times. A great wartime leader, Churchill pursued a disastrous anti-independence policy vis-à-vis India in the 1930s and had an insignificant second premiership in the 1950s—not to mention his mediocre term as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1920s.

Nevertheless, Winston Churchill is considered the greatest Briton of the 20th century. He became Prime Minister in June 1940, when Britain alone stood defiant against the Nazi war machine, and in the words of Isaiah Berlin, mobilized the English language for war. He was the right man in the right spot at the right time.

It is always rather easy to admire wartime leaders. Wartime leaders appeal to simpler, more straightforward virtues, which lends to greater popularity among the masses. Decisiveness, tenacity, stamina—the great virtues of wartime leaders—in combination with strategic vision, are the attributes traditionally associated with strong leadership. Compromise, patience, rectitude—the prime virtues of a peacetime leader paired with the careful fine-tuning of existing policies—often fall flat in comparison.

Simply examine the political careers of Helmut Schmidt, West German Chancellor, and Jimmy Carter, both politicians with clear strategic vision, decisiveness, and stamina and governing during times of relative peace. Carter’s presidency, despite his brilliant work in bringing about the Camp David Accords of 1979 and his farsighted now infamous ‘Malaise Speech,’ generally is seen as an uninspiring failure. Schmidt’s chancellorship, despite playing a tough line on leftwing terrorism in Germany, a confrontational Reagan-like stance towards the Soviet Union, and sound economic policies, which helped Germany weather the global financial storm of the 1970s far better than almost all the other developed countries, plays a distant second fiddle to that of Helmut Kohl, the ‘father of a united Germany’ in the 1980s and 1990s.

These examples show that good timing is ultimately just as important as political talent, and timing itself depends on what the Ancient Greeks called kairos (chance). It is the ultimate decider in what makes a great leader and what does not. Shakespeare had that in mind when he let Cassius deliver the following lines to Brutus in his play Julius Caesar: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world Like a Colossus; and we petty men Walk under his huge legs, and peep about To find ourselves dishonourable graves. Men at some time are masters of their fates.”

Only on rare occasions can outstanding individuals defy both fate and chance and indeed control events rather than events controlling them, to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln. The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, an eccentric young artillery officer of obscure Italian descent, would be such an example, yet even there, timing was crucial. Just imagine Napoleon born in 1815.

However, Renaissance scholar Niccolo Machiavelli in his work The Prince states that Fortuna (chance) is a woman that needs to be beaten down with a stick, i.e. humans can dominate chance. Perhaps our modern singular focus on the individual rather than circumstance comes from this expression. We expect our leaders to transcend circumstance, ‘be masters of their fate,’ and display the uncompromising leadership style of wartime leaders even if contemporary times don’t call for this kind of leadership.

Politicians feed right into this dubious theater. No politician in his right mind would step on a platform announcing that certain things were just out of his/her control and that success or failure of his presidency is dictated by external factors or that, God forbid, they are not the right man for the job because the timing is just not right (e.g., John McCain in the 21st century).

Returning from the Elysian fields of this philosophic excursion, the hard political truth is that in our interconnected globalised world, despite our technological advancements, timing more than anything else is still a major factor in shaping political success. As such, what we need today is not an ostensible new Winston Churchill charging ahead on a perceived adversary, but simply the right man for these tumultuous and immensely complex times. What we need is a compromising realist practicing the Bismarckean art of the political possible while educating the people on the limitations of political leadership and American power. Unfortunately for us, we still haven’t found him, but that fault is largely “not in our stars, but ourselves,” to quote Cassius one last time.