Pollution, Policing, and India’s War on Environmental Activists

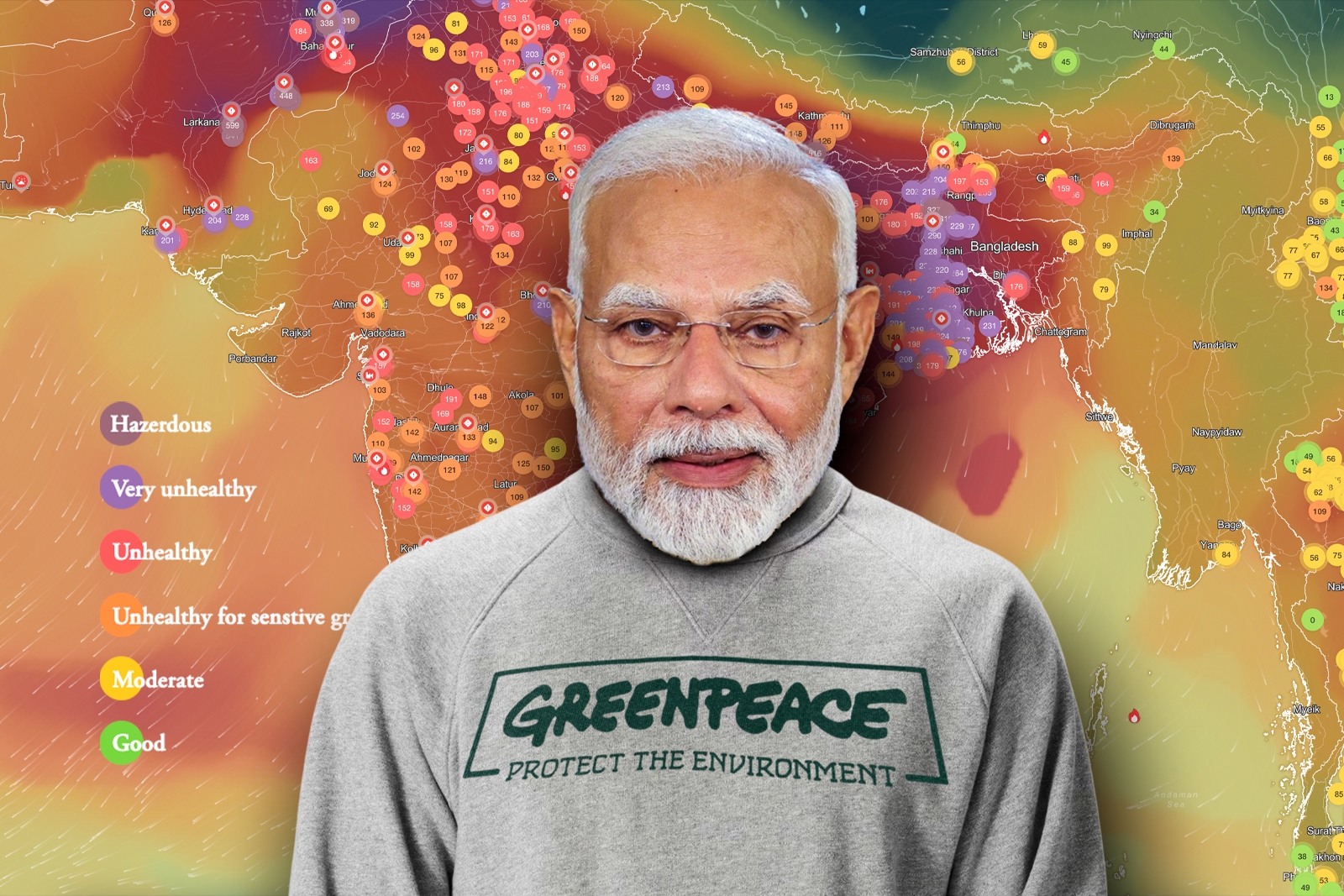

On November 24, a peaceful demonstration at India Gate against Delhi’s escalating air pollution crisis turned violent after a heavy-handed police crackdown. What began as an urgent plea for clean air — a basic public-health demand in a city repeatedly blanketed in toxic smog — ended with chaos, allegations of conspiracy, and a familiar state script for dealing with environmental dissent. By the end of the night, Delhi Police had arrested between 15 and 22 protesters and filed charges that included obstruction, assault, and criminal conspiracy. Far from being an aberration, the episode fits into a broader and increasingly entrenched pattern of state violence aimed at silencing environmental defenders in India.

The demonstrators, largely environmental activists and students, were protesting Delhi’s hazardous air quality, which has reached levels that regularly rank among the worst in the world. They gathered at the C-Hexagon near India Gate, briefly blocking traffic as they called for immediate government action, stricter enforcement of pollution norms, and accountability for industrial and vehicular violations. Students from Delhi University and members of groups such as Bhagat Singh Chhatra Ekta Manch and the Himkhand collective sat on the road for nearly an hour, staging a classic nonviolent protest.

As the demonstration continued, police repeatedly ordered protesters to disperse. The protest, however, took on a more explicitly political tone when some participants began raising slogans in honor of Madvi Hidma, a tribal Maoist commander killed days earlier in a controversial encounter in Andhra Pradesh. Hidma, celebrated in some tribal circles as a defender of forest communities, quickly became a symbol at the protest for a broader politics of resistance: against land dispossession, forced displacement, and mining-driven destruction of forests. Protesters chanted “Madvi Hidma amar rahe” (“Long live Madvi Hidma”) and displayed posters linking his image to ongoing struggles over tribal autonomy and environmental protection, invoking the legacy of figures like Birsa Munda, the iconic tribal freedom fighter.

By invoking Hidma alongside demands for environmental justice, the protesters brought into sharp relief the intersection between tribal rights, forest protection, and resistance to state and corporate exploitation of natural resources. Within tribal-environmental movements, Hidma is often seen less as a mere insurgent and more as a symbol of resistance to a development model that treats forests and indigenous land as expendable. His image at India Gate thus tied Delhi’s smog-choked skies to the forested regions where tribal communities are fighting to defend “jal, jangal, jameen” — water, forest, and land — from extraction and dispossession.

Escalation and Criminalization

The protest, peaceful at the outset, escalated once the Delhi Police moved in with force. Authorities alleged that some demonstrators broke through barricades, used chili or pepper spray on officers, and obstructed government work. According to police, three to four officers suffered eye and skin irritation from the spray, an incident they described as highly unusual for an environmental protest. Two First Information Reports (FIRs) were registered, and the arrested protesters now face a raft of charges, including assault on public servants, obstruction of official duty, and blocking public pathways.

The alleged use of pepper spray became the centerpiece of the police narrative, presented as proof of a premeditated conspiracy rather than a spontaneous act in a tense confrontation. Law enforcement officials framed the protest not just as disruptive but as sinister, suggesting that its true character was hidden behind the language of environmental justice. Yet the forceful response — from deployment of pepper spray to mass detentions — has triggered alarm among civil-society groups about the accelerating criminalization of environmental protest in India. A demonstration that began with a clear, legitimate demand for breathable air was swiftly recast as an “insurgency-linked” event, a familiar tactic in which state authorities portray protest movements, particularly those with tribal or environmental dimensions, as security threats rather than democratic interventions.

Linking Environmental and Tribal Resistance

Madvi Hidma’s significance for tribal and environmental movements lies not only in his identity as a Maoist commander but in the causes he was seen to defend: opposition to mining projects, forest land acquisition, and the erosion of tribal autonomy. In regions such as Bastar in Chhattisgarh and adjoining areas of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Hidma’s name has become shorthand for resistance to a development model that treats tribal lands as sacrifice zones. His biography, in this reading, is less about ideology than about defending communities whose livelihoods depend on forests and rivers.

The circumstances of his death have only intensified this symbolism. Hidma was killed on November 18, 2025, in what state forces described as a successful anti-insurgency operation. Yet allegations quickly emerged that the encounter was staged. Former Bastar MLA Manish Kunjam publicly claimed that Hidma’s killing was a fake encounter, deepening doubts about the legality and legitimacy of the operation. Those allegations have added another layer to the political meaning of his name: not just resistance to mining and displacement, but resistance to militarization and extrajudicial violence in forest regions.

In that light, the India Gate protest was never just about Delhi’s air, though air quality was its immediate catalyst. It was also about who bears the cost of India’s development trajectory, whose lives are deemed disposable, and whose voices the state is willing to criminalize. Environmental degradation, land grabs, and militarized policing in tribal belts are deeply intertwined; the protesters’ decision to invoke Hidma made that connection explicit.

Violence Against Environmental Defenders

The death of an environmental activist during the police crackdown in Delhi fits into a wider and deeply disturbing pattern. Since 2014, India has emerged as one of the most dangerous countries in the world for environmental defenders, with at least 50 killings recorded between 2015 and 2021. Many of these deaths occurred in the context of opposition to illegal mining, resistance to forced land acquisition, and protests against industrial projects that threaten forests, rivers, or agricultural land.

The roll call of activists killed or found dead under suspicious circumstances is long and sobering. Figures such as Poipynhun Majaw in Meghalaya, who challenged cement and limestone interests; Vira Savaliya and Balwani, who confronted sand-mining mafias; and Shashidhar Mishra and Satyajit Mohanty, who exposed corruption and land encroachments, all met violent ends after taking on powerful political and corporate interests. Their deaths illustrate not only the personal risks environmental defenders face but also the broader impunity with which those who profit from ecological destruction operate.

In many cases, local police or other state agencies are not neutral arbiters but active participants or silent accomplices. The resulting climate is one of pervasive fear, in which communities understand that speaking out may incur deadly consequences. Yet activists continue to mobilize, driven by the urgency of protecting their land, water, and forests. The lack of robust legal protections, coupled with the state’s reluctance to investigate or prosecute perpetrators, ensures that those who kill or intimidate environmental defenders rarely face justice.

Securitizing Environmental Dissent

The November 24 protest is part of a broader trend in which environmental activism is treated less as democratic participation than as a security problem. The Indian state increasingly conflates environmental protests with insurgency or anti-state activity, especially when tribal communities are involved. The language deployed — “Maoist-linked,” “Naxal sympathizers,” “anti-national elements” — does not merely stigmatize protesters; it creates a legal and political framework that authorizes extraordinary policing powers.

By framing environmental protests as extensions of insurgent networks, authorities can invoke national-security laws, expand surveillance, and justify preemptive crackdowns. This securitized response effectively collapses distinct categories: peaceful environmental activists, tribal-rights defenders, and armed insurgents are blurred together in public discourse. The result is that protests about forest exploitation, mining, or land acquisition are recast as threats to national integrity rather than as demands for justice and accountability.

The portrayal of the India Gate demonstration as a gathering of “Maoist sympathizers” is a case in point. It allows officials to sidestep the substance of the protesters’ grievances — choking air, unchecked pollution, and dispossession in tribal regions — and to focus instead on alleged links to outlawed organizations. This reframing shifts the terrain from rights and policy to security and law-and-order, where the state’s coercive power is at its strongest and most unaccountable.

Media, Politics, and the Battle Over Narrative

The political and media response to the protest was rapid and revealing. Leaders from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) denounced the demonstration as an attempt to create “anarchy” in the capital, echoing a familiar rhetoric that depicts protest itself as a destabilizing force. Police officials emphasized the use of pepper spray as proof of a “pre-planned conspiracy,” reinforcing the narrative that the protest had been hijacked by violent or extremist elements.

Sections of the media closely aligned with the government amplified this framing, describing the protesters as “Maoist sympathizers” and foregrounding alleged links to left-wing extremism rather than the environmental crisis that brought people into the streets. The core issue — Delhi’s toxic air and its long-term health consequences — was relegated to the background. In its place, coverage fixated on law-and-order angles, arrests, and the supposed subversive nature of the gathering.

This framing is not incidental; it is central to how environmental and tribal-rights struggles are discredited in contemporary India. By depicting environmental activism as a security threat, authorities and friendly media outlets can delegitimize dissent and avoid grappling with questions of governance, inequality, and ecological collapse. The narrative battle over the November protest is thus about far more than one night at India Gate. It is about whether environmental justice and tribal autonomy can be pursued within the democratic sphere, or whether they will continue to be treated as crimes against the state.