Q&A Matthew Kroenig: Coronavirus, China and Authoritarian Regimes

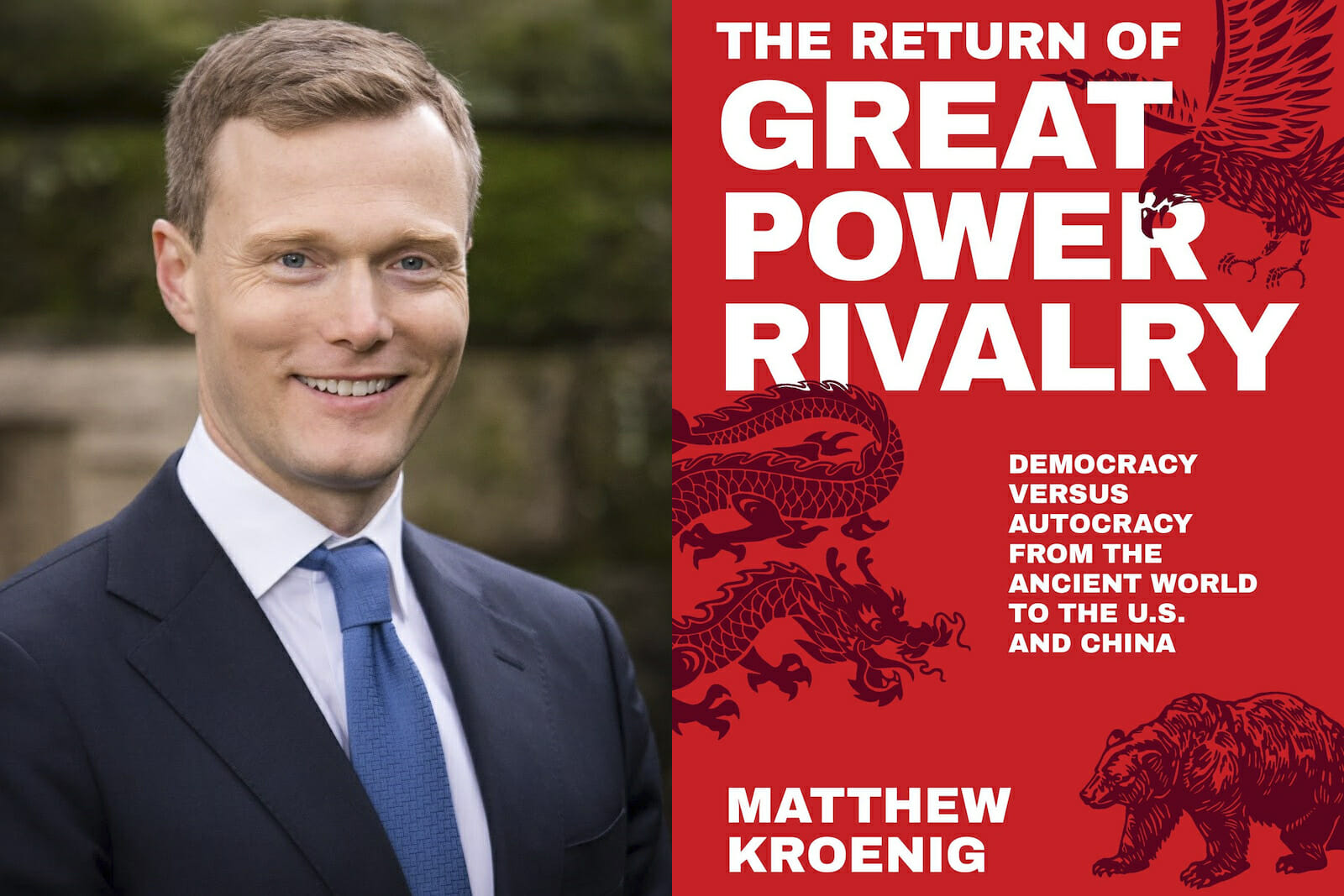

Dr. Matthew Kroenig is deputy director of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council. He is the author of the recently published book, The Return of Great Power Rivalry: Democracy versus Autocracy from the Ancient World to the U.S. and China.

Our conversation, conducted via email, is below.

Thank you for this opportunity Matthew. Your book, The Return of Great Power Rivalry, was published in March before the coronavirus pandemic economically crippled China and many Western economies. When the dust settles, how will COVID-19 fundamentally alter U.S.-China relations?

One of the big questions coming out of the coronavirus crisis will be which model performs better – the U.S. model of open market democracy or the Chinese authoritarian, state-led capitalist model. The answer to this question will have significant implications for which the system looks more attractive to other nations around the world in the coming years. Some of the early initial assessments seem to have concluded that China has performed better, but my book shows that democracies tend to outperform autocracies in great power rivalry. I suspect, therefore, that with the benefit of hindsight, we will assess that the U.S. response, even though it has been halting and patchwork, will produce the more effective outcome at home and for U.S. international leadership abroad. We are already seeing evidence that this is the case with China’s domestic and international response now looking much more feeble than it did just a week or so ago.

Is economics a reliable indicator of a country’s strength?

Economics is one important indicator, but it is not the only one. Diplomatic influence and military power are the two other sources of strength that I examine in my book. I argue that democracies have a number of unique economic, diplomatic and military advantages. On economic strength, many believe that China will soon overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, but in fact, the United States still possesses 24 percent of world GDP compared to only 15 percent in China. Ten years ago, economists predicted that China would overtake the United States as the world’s leading economy by 2020. Here we are in 2020, and it hasn’t happened yet. Now economists are saying that China will overtake the United States in 2030. I suspect the true date at which China will become the world’s largest economy is never. As I show in my book, autocracies with state-planned economies have never maintained high rates of economic growth over the long term.

Has China handled COVID-19 well? In particular, conservatives in Washington are accusing China of not doing enough to warn the West of its danger. On the flip side, Washington was well aware of its potential landfall and it could be argued didn’t do enough to stop its spread.

China initially tried to hide the outbreak. This is a common attribute of autocracies; they are less transparent and tend to be less truthful in their diplomatic statements. China’s failure to disclose the pandemic earlier is what led it to spread to the rest of the world, and the CCP does deserve their fair share of the blame.

People are criticizing the U.S. response, but this is the way that democracies work. The government gets out of the way and allows societal actors and state and local governments to fill the void. The response might be slower, but in the end, the results tend to be more effective.

To make up for its failures, China has tried to engage in “disaster diplomacy” providing medical equipment to countries in Europe but that effort has backfired as well. It turns out that Chinese companies were profiteering, selling faulty equipment that many of these European nations have now rejected and returned. This is something I show throughout my book with autocracies engaging in clumsy diplomacy that often results in backlashes and nations counterbalancing against them.

Is calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” helpful?

It is accurate to say the virus started in China, and we have labeled past pandemic according to their geographic origin, including the Spanish flu and Ebola named after the Ebola River in Congo. In my book, I argue that one of the greatest strengths of democracies is their ability to build effective alliances. One of America’s greatest strengths is its alliances with NATO and other leading democracies. The naming of this virus led to disagreement among the United States and its allies and, at the end of the day, this is just a name. It is not important enough to stand in the way of America’s international alliance relationships.

Will COVID-19 increase calls in Washington to turn inwards and away from engaging in a globalized world? Globalization increased its spread but conversely, countries economically benefit from globalization.

COVID-19 will lead to selective disengagement from globalization. Contrary to conventional wisdom, my book shows that democracies are actually better than autocracies at maintaining a long-term strategic direction. I argue that America’s commitment over the past 75 years to international engagement, including in the economic sphere, has made the United States and the world safer, richer and freer. But this pandemic shows the danger of being too close to China in particular. It was countries closest to China, like Iran and Italy, that were hardest hit, and it is revealed that the United States is too dependent on Chinese medical supplies. This pandemic will lead to an increase in calls for a greater “de-coupling” of the U.S. and the Chinese economies. The fact that the U.S. and China feel too vulnerable to trade with each other is just another indication, as my book title has it, that we are in a new era of great power rivalry.

Will COVID-19 fundamentally alter how Beijing operates? Will Beijing be more open and transparent moving forward should another disease like COVID-19 start in one of its provinces?

No. China’s fundamentals won’t change unless it’s political system changes. The lack of transparency and the tendency to dissemble is a common trait of autocracies. So as long as China is lead by the CCP, we can expect similar results. SARS started in China. In fact, I write in my book about how the Italian plague in the 1600s came to Italy from China across Silk Road trading routes. China has abundant experience with pandemics. They knew what was right. But instead, they decided to try to hide the outbreak.

There have been some calls to ease sanctions on Iran for example to help the country deal with COVID-19. Your view?

Many of these calls to lift sanctions are coming from people who have been calling to lift sanctions on Iran for many years for a variety of different reasons. COVID-19 is just the latest excuse. The United States has long allowed for medical and humanitarian exceptions to its sanctions policy. Lifting sanctions would only put money in the pockets of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. This makes Iran more dangerous, but it doesn’t do anything to solve the COVID-19 problem.

Will COVID-19 lead to any countries being upended? Some on the right have been arguing that the time is now to put even more pressure on Iran or Venezuela. Your thoughts?

We have seen that pandemics have contributed to the collapse of regimes in the past. In the book, I talk about how past pandemics weakened ancient Athens and the Venetian Republic. We are certainly seeing this pandemic straining national governments.

Moreover, domestic political instability is one of the greatest weaknesses of autocratic regimes. In fact, in five of the seven rivalries I studied in my book, the rivalry ended in the collapse of the autocratic competitor. The governments of Iran and Venezuela are brittle. Regime collapse in both countries is likely at some point. Whether it is due to the pandemic or not it is impossible to know.

Your book looks at the great power competition between the United States, Russia, and China. All battles, whether economic or on the battlefield, eventually have to have winners and losers. If the United States prevails what will China and Russia’s next steps be?

One possibility is what we saw at the end Cold War. Russia opted out of competition with the United States for 25 years. That could happen at the conclusion of this new era of great power rivalry and, certainly, another quarter-century of respite from great power rivalry would be welcomed.

But America’s long-term strategy has been to try to create a rules-based international system and to incorporate Russia and China as “responsible stakeholders” into that system. This is impossible with the current generation of leadership in Moscow and Beijing. But as the most desirable long-term goal, the United States and its allies should try to convince future generations of Russian and Chinese leadership to participate in, rather than upend, the U.S.-led, rules-based international system.

Finally, Russia had to postpone its vote to give Vladimir Putin the presidency for life. Aside from China and Russia and a smattering of other autocratic states, democracy is still the norm. Will COVID-19 alter this trend?

Democracy has been backsliding in each of the past 14 years, and we see with COVID-19 some leaders choosing to exploit the crisis as a justification for grabbing more emergency powers. But the most important determinant for the future of democracy is the outcome of the rivalry among the U.S., China, and Russia. We have seen since the ancient world that smaller powers replicate the political systems of the international system’s leaders from ancient Athens to the United States at the end of the Cold War. So, if the United States prevails in this new era of great power rivalry and its democratic system is widely seen as successful, then we can expect to see another wave of democratization around the world. This is just one more reason to root for Washington in this new more competitive era.