Ralph Miliband: The Illusion of Radical Change

Radical conservative critiques often suffer from one crippling flaw: they are mirrors of their revolutionary heritage, apologies for their own deceptions. If you want someone who detests the Left, whom better than someone formerly of the card-carrying, Molotov throwing fold?

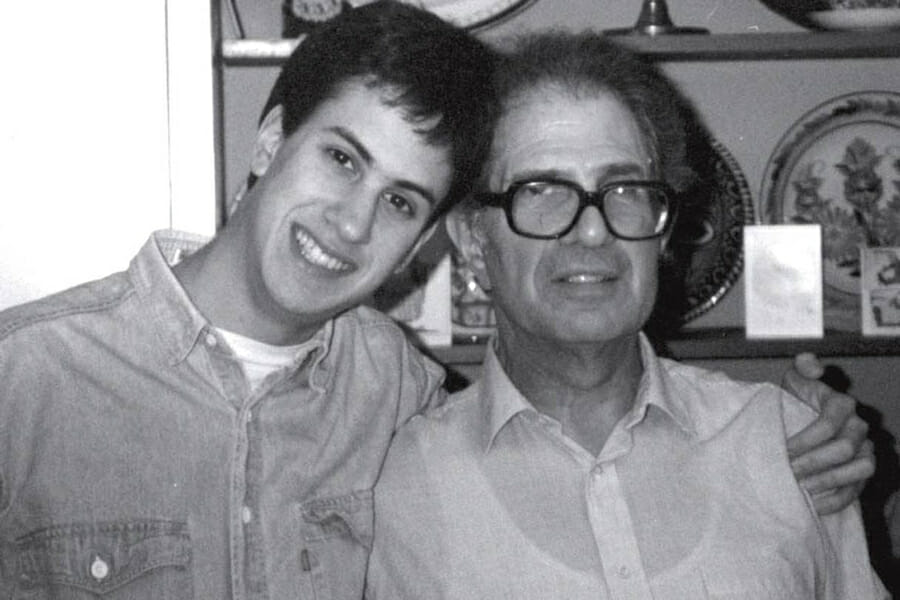

The forces have been recently marshalled against British Labor leader Ed Miliband hover over one distinct legacy: that of his father’s. Ralph Miliband is treated by critics of the British left as enormous, a gargantuan figure who fathered two significant figures of the British Labor movement. While David has taken a back seat for the moment, Ed is very much at the fore in his quest to defeat Prime Minister David Cameron.

On October 1, Geoffrey Levy fired the first salvo about Ed’s purported desire to eradicate Thatcherite Britain. “Ed is now determined to bring about that vision…How proud Ralph would have been to hear him responding the other day to a man in the street who asked when he was ‘going to bring back socialism’ with the words: ‘That’s what we are doing, sir.’”

It would be a bit much to accuse Levy of radical tendencies. It would be fairer to attribute his views to a particular constituency and cerebrally challenged view typical of the Daily Mail. If a sewer could ever own an ideology, it would own the Mail.

Like any such contribution, history and context are not the paper’s strong suit. That many Jewish immigrants would be Marxist is hardly a surprise. That they would want to embrace social justice would be almost a matter of automatic instinct. The exclusion of Jews from spheres of public engagement propelled many to the revolutionary family.

Levy pushes on to extract the links between Red Ralph and Red Ed. While David adopted a more sombre appraisal of the Marxist legacy, claiming it had been “traduced,” Ed moved into the socialist orbit. Views of Ralph on the socialist values of British Labour are noted, including his words at the 1955 Labour conference. “We want this party to state that it stands unequivocally behind the social ownership and control of the means of production, distribution, and exchange.” Hardly the rabid sounding tones of radicalism at a time when the British welfare state was motoring along.

The usual radical conservative clichés are themselves unfolded. Tut tut, Daddy Miliband apparently loathed his country. “The Englishman is a rabid nationalist. They are perhaps the most nationalist people in the world.” He was not the patriotic junkie sort when he sought refuge in England from Nazi Germany. Yes, he might have had a thing or two against the Soviet Union, but not the principle of socialism. Again, hardly radical stuff. Ideas may need blood and guts, but they do not necessarily collapse because of foolish misapplications.

Ed Miliband duly responded, arguing that Levy’s depiction of his father was a lie. “Fierce debate about politics does not justify character assassination of my father, questioning the patriotism of a man who risked his life for our country in the Second World War or publishing a picture of his gravestone with a tasteless pun about him being a ‘grave socialist’” The editors of the Daily Mail, showing true form, retorted that Ralph had attempted to drive “a hammer and sickle through the heart of the nation so many of us genuinely love.” Such is the inanity patriotism invariably breeds.

Others have also chimed in, citing boring politics, amnesia, the time that has passed since the Cold War ended. Benedict Brogan of The Telegraph opined that Ralph was “on the wrong side of the only argument that mattered.” He might well have been a Royal Navy veteran, and a gentle academic sort but the point here was that “Marxism hated – hates – Britain.” Norman Geras, a notable figure of Britain’s democratic left, would have no truck with the designation of Ralph as a bomb-throwing communist suspicious of parliament and freedoms. The “dichotomy” between pure parliamentarianism and pure insurrectionism was false. Ralph Miliband believed in extending, not trimming, democratic institutions “already to be found in a capitalist democracy.”

The great sin of Ralph, or so say such critics as David Horowitz, himself a former Trotskyite and dizzily addled conservative was not changing the tune with the history. Horowitz would have to be so inclined – after all, he left the ideological family of the Left and had been mentored by Ralph himself. Those who leave political movements tend to write apologias for their departures for the rest of their lives. Their self-justifications are often the most trenchant. “For you,” he wrote accusingly in an open letter published in Commentary “the socialist idea is still capable of an immaculate birth from the bloody conception of the socialist state.”

As for the radicalism of Ralph and the supposedly genetic nature of Red Ed’s ideological considerations, Levy is reduced from first harping about sans-culottes extremism, then a concession that blunts both hammer and sickle. Even he had to admit that Ralph died a disappointed figure, one who conceded that British Labour remained “a party of modest social reform in a capitalist system within whose confines it is ever more firmly and by now irrevocably rooted.” A man is still entitled to his dreams.

And thus, we have an observation of what Ed may do in solemn tribute. Thatcherite Britain’s greatest triumph was breeding its imitators. That most reverential of imitators was unreservedly New Labour and the homage-ready response of Tony Blair. Even if Ed is tempted to abandon the “New” tag and take Labour along a pathway that may nod at his father in nostalgic praise, the rhetoric is bound to be richer than the action. Children occasionally pay tribute to their parents, but they can also be entirely indifferent. The conservatives, both neocon and otherwise, can rest easy.