Books

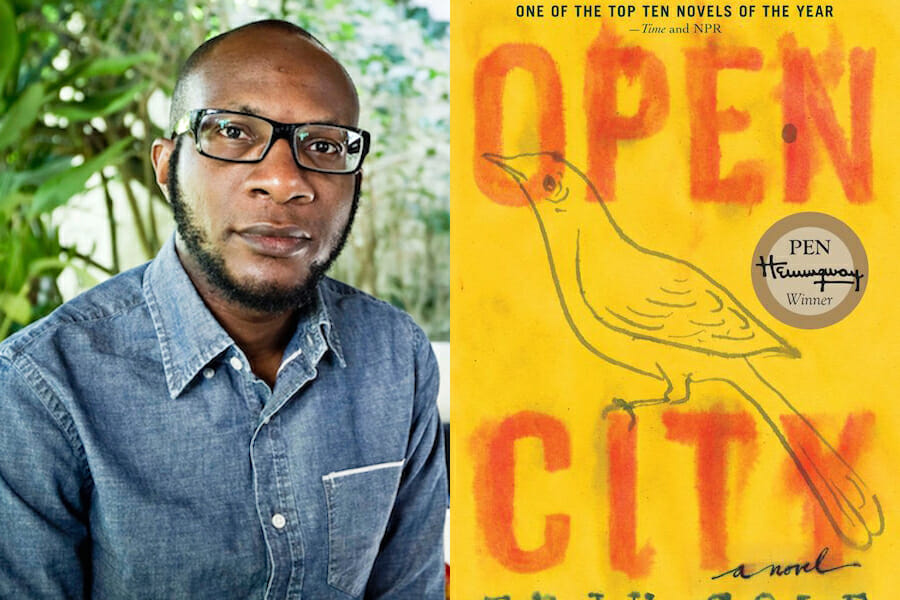

Reflections on Teju Cole’s ‘Open City’

Anyone interested in the world, or for that matter, an affection for the greatest of modern cities—New York—will find Teju Cole’s Open City, a feast for both mind and heart. Cole writes with exquisite discernment about almost everything under the sun, from the details of church architecture to reflections on the lingering impacts of the 9/11 attacks on the urban mood in Manhattan to his childhood memories of Nigeria.

Teju Cole’s Open City is presented as a work of fiction, a novel, but its real interest is not in the story line, or even in the characters as presented by the narrator, which has an autobiographical feel, although this could be an accomplishment of this writer’s craft and imaginative skill, rather than what it seems to be, a disguised replication of the author’s search for meaning and moorings in the world at large, as well as a rich depository of remarkably astute observations on an extraordinary range of interesting topics. Cole in Open City delivers a master class in everyday awareness continuously transforming the ordinary experience of the non-heroic narrative voice into a quite extraordinary immersion in the lifeworld of the city.

This is a story of what I would call voluntary displacement, somewhat reminiscent of Edward Said’s partial memoir, Out of Place. Both of these gifted and multi-talented men chose to live as expatriates but without losing their attachment to their home country. There are also some dramatic differences, as well. Said became passionate about his Palestinian identity, a badge of honor for him, and the focus of his concerns in the final decades of his life, while Julius the fictionalized ‘I’ of Cole’s narrator is totally preoccupied with his private feelings, perceptions, and experience, noting public concerns, but avoiding engagement by deliberately adopting a modulated apolitical stance. Said as a high profile Palestinian in America in this period almost ensured that he would find himself embattled, which he was, especially as a professor at Columbia University who spoke out in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle.

More generally, being a Palestinian, or any kind of Arab or Muslim, in New York City is certainly a different reality than being Nigerian, or even an African. Although the difference may not be as great as it might first seem. Julius is fully conscious that history has not been kind to those with his racial identity. He makes note of the frequent reminders throughout the city that Africans were not that long ago profitably traded as slaves by New York bankers or subject to colonial atrocities, as in Belgium, where Julius visits for several weeks.

The ironic tone on race reaches a paradoxical climax when Julius is mugged and badly beaten by African American hip-hop teenagers during a walk in the vicinity of Morningside Heights.

Julius reports this violent incident almost in a journalistic tone, refraining from moralizing commentary and even self-pity. He leaves for readers an implicit challenge to draw out the deeper implications of the event, which include a recognition of the difference between the ‘civilized’ Julius and his ‘savage’ attackers, which is a way of saying that race counts, but socialization counts more.

Yet, Julius carries his irony to a fever pitch of self-indictment when confronted by Moji, the older sister of his childhood friend in Nigeria, who reminds him of how he sexually abused her at a drunken teenage party, and how that incident caused her enduring pain. Just as slavery is forgotten by New Yorkers who pound the pavements of Wall Street, Julius forgets what was unpleasant in his past, not even recognizing Moji when they run into each other on a Manhattan street, and she calls out his name. The unarticulated morality here is profound and in keeping with the narrator’s sensibility: we are in denial about the wrongs we do to others, as is Julius, while we being haunted by those done to us, as is Moji. This fictional template fits much that takes place in our collective lives. Compare, for instance, the contrast between the collective official memory of Hiroshima in the United States (shortened the war, saved lives) and the way the event is perceived in Japan, and elsewhere (unspeakable atrocity on a par with Auschwitz).

There are also notable differences between author and narrator that make the facile assumption of an autobiographical novel suspect. Cole is pure Nigerian, while Julius has a German mother along with a Nigerian father, which underscores a type of hybridity that can never even aspire to achieve a ‘normal’ identity. Wherever Julius is, including Nigeria, he is destined to be an outsider. In the novel Julius is finishing a psychiatric residency at Columbia Presbyterian in New York dealing with patients who are burdened with a variety of mental disorders, while Cole is described as “writer, photographer, and professional historian of Netherlandish art” in an author’s note.

As Julius takes his long walks through the city he contemplates the troubled lives of his patients, and is aware of how little he can do to improve their lives, how limited has been medical progress with respect to mental illness. Julius muses about the nature of severe depression and other illness of the mind that afflict patients identified by letter, ‘V’ or ‘M,’ an indication of Julius’ adherence to the code of anonymity in his professional calling. There are intimations, but nothing explicit, that there may be analogies between these private agonies that Julius confronts at work and the grotesque pathologies of our collective existence as a species.

Julius is estranged from his German mother who lives in Lagos while missing his recently dead Nigerian father. Thus he has little reason to return to Nigeria for visits. Instead he searches for his beloved German grandmother who he believes is living in Brussels, and once there is much more enthralled by the ambience of European culture than anything that the non-West has to offer and by a new city to explore. While in Belgium, his supposed reason for making the journey fades into the background, and is replaced by his chance acquaintance with a couple of Moroccan immigrants, who sought refuge from an oppressive monarchy in their native country. To leave for Europe was for them to realize their dream of political and intellectual freedom, but upon arrival disillusionment immediately their fate. They were daily challenged by an increasingly vicious and omni-present Islamophobia. Their reaction was to learn economic and social survival skills needed to remain in Brussels, while inwardly converting their disillusionment into a blend of anti-American radicalism and an embrace of Islam.

The resulting conversations between Julius and Farouk, and his friend, Khalil, are fascinating exchanges of views and perceptions. The narrative voice controls the shape of the dialogue, but it has an authenticity that fits with the variety of experiences and viewpoints that give vibrancy to the book. In essence, Farouk and Khalil hold somewhat stereotypic left views on such key issues as Israel/Palestine and the 9/11 attacks on the United States, although they distance themselves from the tactics of terrorism, they empathize with the motivations of the terrorists who are regarded as having legitimate anti-imperial grievances. In contrast, Julius, is far more detached during the conversation, reacting in a measured apolitical and evasive tone, manifestly distrustful of dogma in any form. When asked directly for a response, he speaks of attitudes toward Israel in the United States without revealing his views, choosing to occupy a neutral, uncommittal space, and somewhat derisively attributing highly critical views on Israel to “left-leaning magazines and journals.” He challenges the stereotyped views on the conflict, including that all Americans are unconditionally pro-Israeli, by explaining to these two ardently pro-Palestinian Moroccans: “There’s strong leftist support for Palestinian causes in the United States. Many of my friends in New York, for example, think that Israel is doing terrible things in the Occupied Territories.” (p. 118) By referencing ‘many of my friends’ keeps his own attitudes hidden from the reader, but they can be presumed to be more balanced, less partisan. Julius goes on, “there’s also the perception that we share elements of our culture and government with Israel.” The use of ‘we’ as America and ‘our’ as American in this sentence is an important signifier of Julius’ primary attachment to his chosen place of residence rather than to his African place of origin.

The Moroccans, as is the case with many progressives around the world, view the Israel/Palestinian conflict as the most important contemporary litmus test of international morality, as well as an unresolved remnant of the anti-colonial struggle. They are perplexed by why the Palestinians have failed where almost all colonized people have succeeded, and in their search for an explanation, reach for straws. In this spirit, Khalil challenges the uniqueness of the Holocaust, and alleges that to relegate the other countless genocides to a secondary status functions as a device, diverts public attention, especially in Europe, from the injustices imposed on the Palestinians, serves to silence criticism of Israel, and to punish those who dare raise questions about the uniqueness that Jews attribute to the Holocaust. “Did the Palestinians build the concentration camps? He said. What about the the Armenians: do their deaths mean less because they are not Jews.” (p.122) An agitated Khalil then proclaims, “(f)orget the Cambodians, forget the American blacks, this is unique suffering. But I reject the idea. It is not a unique suffering. What about the twenty million under Stalin? It isn’t better if you are killed for ideological reasons.” Julius is obviously made uncomfortable by such hectoring rhetoric, and does his best to change the subject by ordering food in the restaurant.

He fails. Farouq “steers the conversation back,” letting on that he is not unfamiliar that Jewish critics of Israel exist and several are living in America. In this vein, he recommends that Julius should read Norman Finkelstein’s searing expose of the holocaust industry, which he says deserves special respect, not only because Finkelstein is Jewish, but because his parents were Auschwitz survivors. Julius admits that he has not heard of Finkelstein, and when Farouq offers to write down the title, Julius indicates that this is not necessary as he will remember it, but this is said in such a way as to convey disinterest, and to let the reader know that he has no intention whatsoever of following up. Throughout the entire book Julius seems deeply uncomfortable with passion and partisanship unless it is historically removed from the present or is apprehended in artistic form.

Farouq is depicted as a kind of fugitive philosopher from the non-West who had hoped that he could cope with the poverty of his Moroccan background working in Belgium as a janitor, while devoting himself to his studies. He declares that he was driven by the grandiose ambition of becoming “the next Edward Said! I was going to do it by studying comparative literature and using it as a basis for societal critique.” (p.128) Proceeding on this path after arriving in Brussels, he wrote an M.A. thesis on Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, which was rejected by a Belgian university on the grounds of plagiarism. “They gave no reason. They just said I would have to submit another one in twelve months. I was crushed. I left school. Plagiarism? The only possibilities are either that they refused to believe my command of English and theory or, I think this is even more likely, that they were punishing me for world events in which I had played no role. My thesis committee had me on September 20, 2001..That was the year I lost my illusions about Europe.” (p.129) Again Julius offers no response, even refraining any comment on the rather strained effort of Farouq to explain the arbitrary rejection of his thesis as a punishment to be visited on all Muslims after 9/11. Julius does not hide his distaste for the Farouk’s extreme rejection of the West, which is the counterpoint to his own cautious constructions of a life and career in New York undertaken with a full awareness of the crimes present and past of the West. If this is a correct reading, then one wonders whether Coles lineage is better tied to anglophilic V.S. Naipaul rather than to Said.

Julius makes his own position clear both by seemingly ignoring Farouq’s advice to read Finkelstein and even more emphatically by mailing him a copy of Kwame Anthony Appiah’s Cosmopolitanism, a diametrically opposed intellectual posture to that of political engagement. The choice of Appiah as a preferred alternative to Finkelstein is a perfect expression of Julius sensibility, and a telling sign that he is self-aware. Appiah is a much heralded and impressively cultured exponent of an apolitical cosmopolitanism that affirms rootedness in the familiar landscape of home with an appreciation of the world as a whole, including its many forms of strangeness and diversity. For Appiah a true cosmopolitan celebrates both the homeland and the world, and privileges that which is near at hand over all that is distant. As with Cole, Appiah has a superb command of the English language, as well as a vast intellectual comfort zone that manages to encompass the whole of Western thought. It is worth noticing that Appiah, like Julius, but not like Cole, has an African father and a European mother, and chooses to leave Africa for a life in America.

While mailing Cosmopolitanism at a local post office, an African American clerk greets Julius with mock familiarity as “Brother Julius.” The clerk announces that he is a performing poet and recognizes at first glance that Julius is a visionary; hence that they have much in common, and should get to know each other. Julius brushes off this unwelcome approach with a hypocritical assurance that he will keep in touch, informing the reader his true feelings: “I made a mental note to avoid that particular post office in the future.” (p.188) I do not interpret this to be black on black racism, but rather an unabashed expression of snobbery and intellectual elitism. Julius showed clearly that he was offended by the purported camaraderie of this uneducated postal clerk who had evidently proceeded on mistaken assumption that their shared skin color was sufficient to make them ‘brothers.’

Julius consistently shows that he is not fond of any intense attachment, while at the same time exhibiting his somewhat anguished solitude. Even those who are too worried about climate change offend Julius’ sense of cool. As usual, his words of rebuke are carefully chosen: “…I was no longer the global warming skeptic I had been some years before, even if I still couldn’t tolerate the tendency some had of jumping to conclusions based on anectdotal evidence; global warming was a fact, but that did not mean it was the explanation for why a given day was warm. It was careless thinking to draw the link too easily, an invasion of fashionable politics into what should be the ironclad precincts of science.” (p.28) Of course, Julius is correct to make the distinction between a warming climate cycle and the temperature on any particular day, but by dwelling on this minor point he sidesteps any reference the serious dangers posed by climate change, as established by a consensus of experts. Instead Julius contents himself by complaining about those who embrace ‘fashionable politics.’ It is this refusal to engage the world, and its destiny, that I find most disturbing about the Cole/Appiah/Naipaul worldview. I find their shared cosmopolitanism a posture of a superior mind that seems frightened of taking stands that might be treated as controversial in public space or seen as too humdrum for such finely attuned intellects. Such detachment operates as a denial of love for the world and signals an unwillingness to lift a finger to reduce human suffering.

Along these lines Julius offers some rather strained observations on matters large and small, always worth pondering for their style even if not for their substance. For instance, Julius notes without qualification, “[w]e are the first human beings who are completely unprepared for disaster. It is dangerous to live in a secure world.” (p.200) This sentiment seems spoken by Julius from within his cocoon of condescending detachment. Not only the mounting dangers associated with climate change, dangers now admitted at even the highest levels of government, but also living decade after decade beneath a nuclear sword of Damocles should at least establish remove from serious discussion any claim that we are living in ‘a secure world.’ True, there may not be the existential immediacy of earlier ages when the threat of epidemics, natural disasters, and bloody tribal warfare created pervasive and acute insecurity, but in our time there is more reason than ever before to apprehend the precariousness of our modern way of life, and even the fragility of the human species that appears so far heedless of the wailing sirens of planetary distress.

By establishing Julius as such a precise and subtle commentator on many aspects of the passing scene, Cole makes his readers think hard, while enjoying the pleasure of the beautifully crafted prose. The narrative smoothly navigates the succession of moods, experiences, and memories that lends an aura of coherence to this novelistic journal that delivers the reader to nowhere and everywhere. Despite my admiration for Cole’s artistic achievement, what a flock of admiring reviewers agree as the excellence of his ‘debut novel,’ which has received several honors, my experience the book is more ambivalent. This is partly, as earlier noted, a discomfort with attitudes that are fully aware of injustices and yet opt for a response of passivity. Also it is partly the overall impression of being under the spell of a rare, and ultra refined version of Orientalism, which is paradoxically and obliquely acknowledged by references to Edward Said. Julius is wonderfully articulate in describing the nuances of painting, poetry, literature, and especially music. Super-sophistication is exhibited not by namedropping, but by treating the reader to extremely illuminating comments on particular paintings, buildings, musical compositions and memorable performances.

Truly Julius is a man of arts and letters, but almost exclusively those of the Western world. The artists and writers mentioned are prominent in the Western canon or Westernized, and there is only a passing reference to two Chinese poets revered in the West and none at all to such African stalwarts as Soyinka and Achebe. We readers are left with the misleading impression that any celebration of aesthetic cosmopolitanism needs to be totally anchored in Western creativity. This may not be Cole’s intention, but it reflects my experience of this fine literary work. Cole demonstrates he is not only of a master of English but also an almost omniscient observer of all that is worth noticing and appreciating in the world around us. The fact that Julius refuses either to judge or to apologize for either private or public wrongdoing can be interpreted generously as the author’s modesty or more harshly as his arrogance. At this point I am not sure which, and maybe it is best grasped as a Hindu mixture of both, a non-Western infrastructure of contradictory feelings for the things and beings of this world, including its good and evil aspects. So conceived, maybe the Cole worldview after all transcends its self-imposed Western boundaries.