Refreshing the Camelot School: Kennedy Hagiography at Sixty

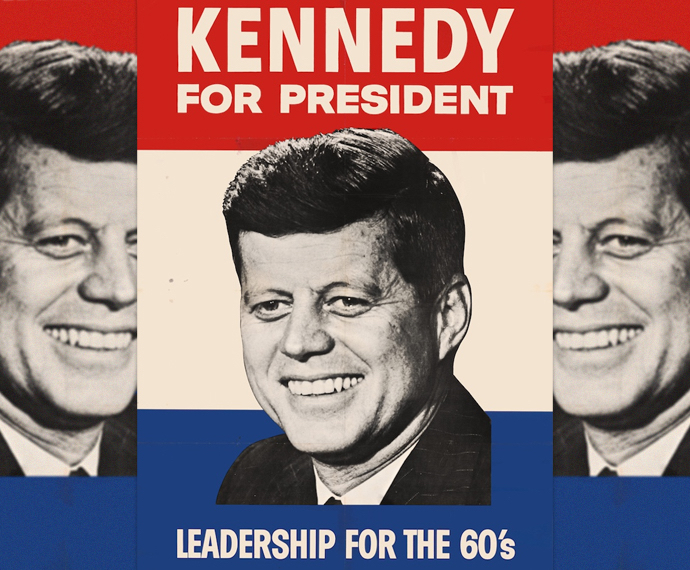

Camelot, the sweetly sentimental shorthand for a shortened U.S. presidency, has generated a mythopoetry so rich it turns the stomach, clogs the intestines, and soils the historical record. With its effacing tendencies, its soppily loyal hagiographers, its ghastly, moist worshippers, anniversaries are the best occasions to shine. Six decades have passed since President John F. Kennedy was slain in Dallas, and the miasma of psychic doubt and veneration has only slightly abated.

As with each decade, the conspiracy behind the death of the Republic’s youngest Caesar is always revisited with a pilgrim’s myrrh-perfumed dedication. The energy with which this is pursued has as much to say about the cloying romance of Camelot rather than its reality: the bullets did not merely kill a man but a dream, a project yet to be realised in glorious bloom. The disputed mechanics of the killing also make their reappearance at each turn: the implausible “magic” bullet that could never have done the dreadful damage it did; the unwarranted certitude of the Warren Commission on Lee Harvey Oswald being the lone eagle-eyed gunman; the sinister role, alleged or otherwise, played by the security services, including the Central Intelligence Agency.

There are notions that U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War would have been halted, if not suspended altogether. The Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union would have been, not just eased but thawed by the handsome wonder in the White House who was, rather fittingly, known as the President Erect. Civil rights legislation would have passed, miraculously, despite an obstructive Congress. In essence, what was achieved by his almost brutally pragmatic successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, would have taken place – at least on the domestic front – while ignoring the bloody cockup in the paddy fields of Asia.

Much of this yields a body of custard-clinging work that is, at best, hagiographical and, at worst, hysterical. The material firstly issued from the Kennedy court historians, including Ted Sorensen and Arthur Schlesinger Jr., their work floating in a permanent celestial orbit that came to be called “The Camelot School.” “The JFK White House was a hagiography factory from the get-go,” remarks Thomas Meaney with incontestable accuracy.

Schlesinger admired JFK and his brother, Robert, so much so that studied omissions on character were not only entertained but automatic. No reference to bedroom acrobatics, for instance. It prompted a famous assessment by Gore Vidal of A Thousand Days as a work of novelistic fiction, “the best political novel since Coningsby.”

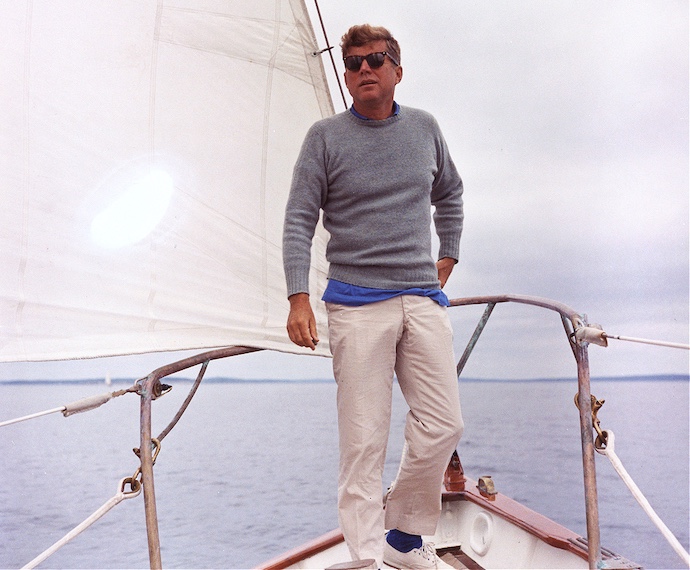

Later works also fail to escape the courtiers’ grip. In 2003, Robert Dallek’s An Unfinished Life gives us a study that is almost embarrassing. We struggle to find, even at the end of such a text, a figure to admire, be it his bogus literary exploits behind the Pulitzer Prize-winning Profiles of Courage (he would do well in the charlatan-filled groves of the modern university), or whether his addition of being on the job constantly distracted him from his actual job.

Regarding the latter, Dallek has the cringeworthy remark: “The supposition that he was too busy chasing women or satisfying his sexual passions to attend to important presidential business is not borne out by the record of his daily activities.” Then comes the throwaway line, true gem: “And, according to Richard Reeves, another Kennedy historian, the womanizing generally ‘took less time than tennis.’”

The pharmacological smorgasbord Kennedy consumed, despite being described in considerable detail by Dallek, is sniffed at as a minor irrelevance to presidential duties. “Judging from tape recordings of conversations made during the [Cuban Missile] crisis, the medications were no impediment to long delays and lucid thought; to the contrary, Kennedy would have been significantly less effective without them and might not have been able to function.”

Just last year, Mark K. Updegrove also added his bit to the Kennedy canon of worship with Incomparable Grace, doing little to tarnish his icon. Familiar themes are recycled. At least Updegrove takes note of the sexual proclivities (“rampant and reckless” no less) and the efforts by the president, the family, his aides, and doctors to conceal “illnesses and medical remedies from the press.” That he refuses to even consider that the pharmacopeia diet might have at least raised a question of compromising the office is telling. It goes to show that, whatever reservations are shown, Updegrove cannot get away from the Camelot allure that grants Kennedy higher powers even as he shows evidence of distinct failure. Yes, he made mistakes, but he noted the lessons.

Other efforts focus on the “What would have happened” school of crystal ball gazing with near delusionary fervour. They are characterised by such efforts as Jeffrey Sachs, whose 2013 tract on the president’s 1963 speeches about war and peace are meant to reveal an extraordinary visionary cut down in his prime. He makes much of the June 10, 1963 oration regarding what is said to be a less belligerent approach towards Moscow.

In June this year, Sachs would even dream about what his hero would do regarding the war in Ukraine, the sort of tea leaf reading that is nothing less than prophecy. He would embrace a different route to peace taken by the Biden administration. He would not denigrate Russian President Vladimir Putin. He would keep the communications open with Moscow. We shall never know.

Camelot’s cerebral retardation continues to exert its force in such serious efforts as those of Stephen F. Knott of the United States Naval War College. Published in October last year as Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy, Knott’s way of doing so is unsatisfactory. He is found praising Kennedy’s Civil Rights Act of 1963 and defending him about his dubious role in the Bay of Pigs disaster. He encourages Kennedy’s public utterances to be “read with caution,” though still believes that “the ones that support the thesis that he would have prevented Vietnam from becoming an American quagmire” remains credible. Regarding the latter, it would surely be more credible to suggest that Kennedy salted the earth that would eventually yield the terrible harvest of Indochina policy under the Johnson administration.

The JFK legacy now has now moved beyond the textual teasing of biographies to celluloid realisations. Netflix, for instance, promises a limited series on the president’s life. Oliver Stone continues his crusade through screen and interview, focusing in macroscale on the killing. It is not hard to imagine that the modern President Kennedy would have happily dived into (and onto) every known social media platform and cinematic medium to prosecute and shape Camelot’s legacy. But nothing gets away from the icy realisation that the man, even as he was felled, did not cut the mustard. The rest is hagiographic musing.