Refugees and the Moral Responsibility: Interview with Serena Parekh

While the European Union grapples with the largest refugee crisis since World War II, there’s a heated debate going on as to whether taking in asylum-seekers and helping them resettle is a moral and legal responsibility which the EU countries should assume.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, more than 6.6 million people have been internally displaced as a result of the five-year-long civil war in Syria. The devastating war has produced over 4.8 million refugees. The refugees fleeing war and turmoil at home embrace the extreme hardships of getting to the EU borders by all means at their disposal, including boarding unsafe overloaded, boats where they are charged several thousand dollars to take them to Europe. However, many of these bleak journeys end in misery and death. More than 3,500 migrants died in the Mediterranean Sea in 2014 as their vessels capsized in international waters. Most of the refugees traveling by boat arrive at Italy, Malta, Greece and Spain and immediately file applications for asylum or relocate to other EU countries.

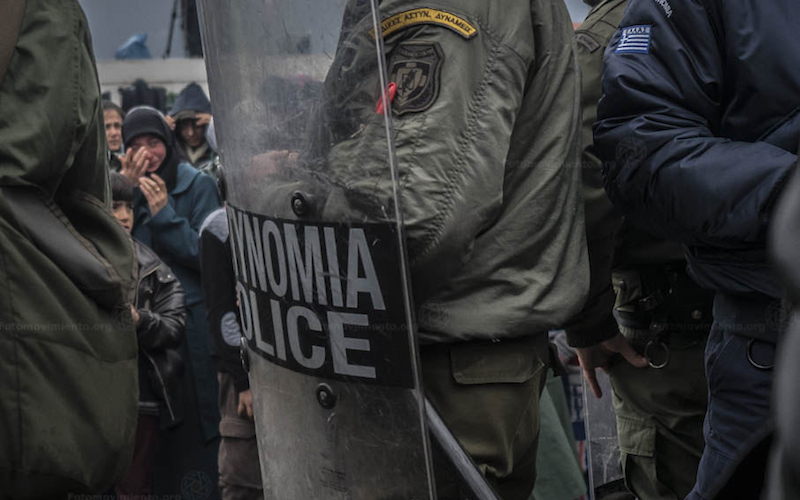

The EU member states are arguing over policies to distribute the asylum-seekers and some have tightened their border security measures and set limits on the number of refugees they will admit annually.

A Northeastern University professor believes the refugee crisis is threatening the “Euro-American economic domination” as people and governments in the West face the possibility of making compromises that will affect their standard of living.

“Genuinely aiding the millions of people who have been harmed and displaced by the civil war in Syria and the many other conflicts around the world may require a sacrifice among those living in the wealthiest parts of the world, perhaps even a sacrifice in our standard of living or resources,” said Prof. Serena Parekh.

“It may turn out that we cannot justify our economic dominance and support of extreme inequality in the face of so many needy, vulnerable people on the shores of Europe,” she added.

Serena Parekh is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Northeastern University in Boston, where she is the director of the Politics, Philosophy, and Economics Program and editor of the American Philosophical Association Newsletter on Feminism and Philosophy. Her forthcoming book is Refugees and the Ethics of Forced Displacement is due to be released in May.

Prof. Parekh responded to my questions about the EU refugee crisis, the rise of anti-immigrant sentiments in the West and the moral responsibility of European governments vis-a-vis the growing number of asylum-seekers from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere in the region.

The rise of far-right groups with anti-immigration agendas in several European states has alarmed thousands of asylum-seekers fleeing Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and other crisis-stricken countries in the region. The former Polish Prime Minister Jaroslaw Kaczynski has warned that the Muslim refugees bring “parasites and diseases” with them. The leader of the Swedish Democrats, Jimmie Åkesson, has asserted that “Islamism is the Nazism and Communism of our time.” What are the root causes of antagonism towards the refugees by the right-wing parties and politicians in Europe, which has seemingly taken on racist and xenophobic implications?

Fear of the other, however the other is defined, is among the oldest and most reliable themes in politics. The Polish Prime Minister is not wrong – refugees are often wounded, traumatized and sick, and yes, bring disease. Whether or not you see this as a reason to exclude them is independent of that, and rooted in other worries and political calculations. There are others, for example, who see the fact that many refugees are sick as a reason to aid them, not exclude them. Fear of the other is often intensified of course when there is a feeling that the outside group is somehow threatening to one’s culture, language, economic integrity, ability to access resources, etc.

The fierceness of the antagonism, I think, is partly due to its political expediency. Hostility towards outsiders is an easy way for a political leader or group to seem like the good guy, the one standing up for the people, the one who’s looking after the interests of citizens. In this way, Kaczynski is not that much different from Donald Trump. It’s a convenient though highly destructive mode of populism.

In terms of the specific fear of Islam and the rise of acceptable anti-Muslim rhetoric, this shift has been happening for quite a while. Since 9/11, populist leaders of all persuasions have latched on to the idea that Islamism is dangerous like Nazism. The problem of course is the conflation of extremism that is done in the name of a particular interpretation of Islam, and Islam itself.

What is the root cause of the fierce antagonism towards refugees? In part, the refugee crisis – not only its scale, but also the fact that we have failed to contain it abroad – threatens Euro-American economic domination. Genuinely aiding the millions of people who have been harmed and displaced by the civil war in Syria and the many other conflicts around the world may require a sacrifice among those living in the wealthiest parts of the world, perhaps even a sacrifice in our standard of living or resources. It may turn out that we cannot justify our economic dominance and support of extreme inequality in the face of so many needy, vulnerable people on the shores of Europe. If we concede that they are deserving of our help, many fear, we may be required to make substantial changes in order to provide this aid.

You noted in a recent article that almost 99 percent of the world refugees, 59 million people, are forced to spend years and even decades in underfunded refugee camps, and are never granted full citizenship rights in the countries where they seek asylum. Is it a state policy to keep the refugees in concentration camps that rely on international aid for survival? Isn’t this practice counter to international law?

To clarify, refugee camps, as terrible as they are, are not concentration camps. It’s important not to make false analogies with the Holocaust.

The situation you describe is not the result of intentional policy on the part of the international community. But it is the result of different states acting according to what they perceive as the best interests of their states and their citizens. For example, Western states see it as being in their interest to only resettle a relatively small number of refugees. States that host large numbers of refugees see it in their interest to keep refugees contained in spaces far from local populations when possible, such as in refugee camps. The UNHCR ends up supporting these policies because they see repatriation – returning home when the conditions which forced refugees to flee cease to exist; this is one of three “durable solutions,” the other two being integration into the host state and resettlement in a third state – as being in the best interest of refugees.

They see it as best for refugees themselves if they can be kept in camps “temporarily” until the conflict ends so they can return home eventually. If we understand the situation in this way, we see why it’s so tolerable for states and the international community to ignore their ethical responsibility to refugees. Every state thinks of itself as helping refugees in a way that is consistent with its self-interest. This is why I argue that the moral harm of the current situation can only be seen when we look at the problem as a whole, as a global problem, and not from the point of view of different states or actors. The collective outcome of every state acting according to its own self-interest is the current status quo, [that is] the prolonged containment of refugees, often in terrible circumstances.

Yes, “warehousing” of refugees does violate international law. The Refugee Convention clearly states that refugees ought to have freedom of movement as well as the right to earn a living, after a 3-year period, if states are unable to provide this immediately. The principle of long-term encampment is that refugees must remain dependent on the international community and are not free to move around a host country in search of work or security.

The Danish parliament has recently approved controversial legislation, allowing the immigration authorities to seize the valuable items the asylum-seekers bring with them, including jewelry and cash, as an effort to offset their resettlement costs. Sweden has also tightened security measures at its borders and rejects immigrants who don’t have valid identification, including passports. The Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban has likened the migrants to “an army,” and has built a steel fence along its borders with Serbia and Croatia to exclude refugees. Are the EU countries ignoring humanitarian responsibilities?

Yes. States have often known that one way to “handle” a refugee crisis is to make conditions so bad that refugees themselves either no longer want to come or choose to return home if they are in the country already. Tightening borders, taking valuables, building fences are certainly designed to make it harder for refugees and thus discourage them from coming. Yet it is a way of avoiding responsibility that does not violate international law as would, for example, sending refugees back when they have a legitimate fear of persecution. This would be a violation of one of the most widely accepted principles of international law, non-refoulement.

It’s important to note that Western countries have no legal obligations to those who are fleeing poverty, that is, to individuals who are not fleeing persecution. In fact, this is one of the grounds that states are using to justify their actions – they want to keep out “economic migrants” so that they can better help “legitimate” refugees. Of course to anyone fleeing starvation, which may be the result of war or policies of their governments intended to punish or harm certain groups, this distinction is meaningless, but it is one nonetheless that most states try to adhere to.

One of the most efficient ways to address the refugee crisis is to ensure that the civil war in Syria is concluded and ISIS is defeated. Is there a strategy on the U.S. and EU’s agenda to deal with ISIS through diplomatic or military channels?

The Syrian war is almost unprecedented in this way. Other conflicts that produced refugees were much better understood; states at least had a sense of what to do, whom to support, what was needed to stop the conflict, even if the political will was not there. As far as I can tell, there is no consensus on what should be done to stop the civil war, and even whether or not we should allow Bashar al-Assad to stay in power, as Jimmy Carter argued, or whether getting him out of power ought to be the goal as Obama has maintained. How to achieve stability in Syria is still being debated and worked out. It is now a conflict not only between the different fractions inside Syria, but also between those outside of it – Russia, Iran, the US. To quote Jimmy Carter, in order to end the war, states need to make concessions, but “the needed concessions are not from the combatants in Syria, but from the proud nations that claim to want peace but refuse to cooperate with one another.” One of the deep tragedies of this situation is that for all the horror it has produced until now, there is still no end in sight.