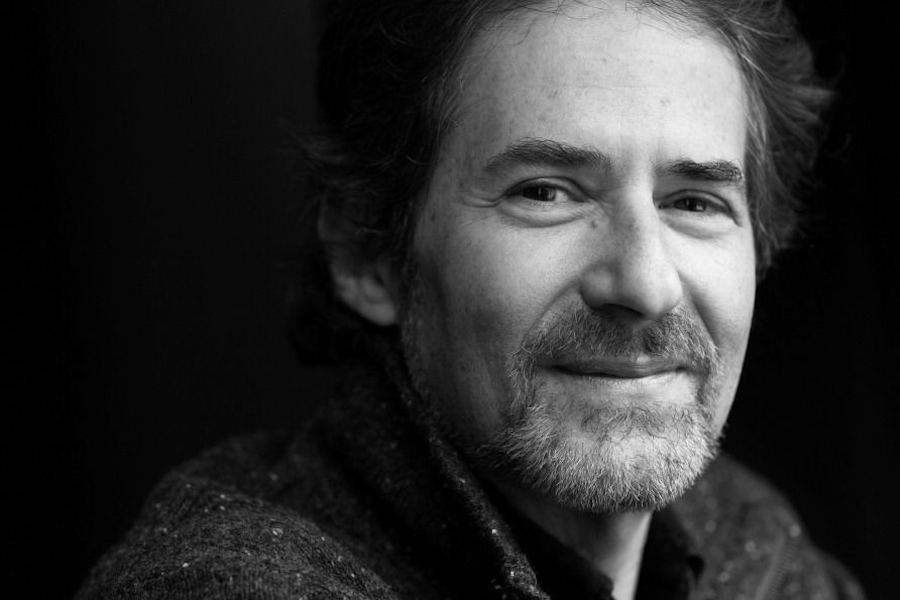

Remembering Composer James Horner

Composer James Horner’s passing in June is a colossal loss to the music world. His creativity was still ablaze. His heart was in his work.

Last year he debuted a concert work, Pas de Deux. This year another new concert work, Collage, premiered, and Horner completed three feature film scores: Southpaw, The 33, and Wolf Totem. The 33 has not yet been released on album in North America but the other new scores have enjoyed positive reception.

The past two years saw a master storyteller returning to form, his credentials established long ago. Although best known for Avatar (2009), Braveheart (1995), and Titanic (1997), Horner accomplished much more during his long career.

His best scores are textbook exhibits of music echoing the emotional beats of the film. The score to Glory (1989) speaks to the exultation and tragedy of the 54th Massachusetts regiment during the American Civil War. Apollo 13 (1995) conveys the crew’s winged idealism for the NASA rocket launch, the solitude of the dark side of the moon, and the fiery intensity of splashdown. Legends of the Fall (1994) tells the struggles of the Ludlow family in the early 20th century Montana wilderness.

In the Ludlows theme, one senses the civility and stature of Anthony Hopkins’ character. Thunderheart (1992), a forgotten score to a forgotten film, voices the pride and suffering of the Lakota Nation. The Land Before Time (1988) is a marvel of tenderness, innocence, and frolic.

The world of baby dinosaurs somehow finds its natural voice in ballet stylings reminiscent of Tchaikovsky.

Horner was a fine stylist as well as a versatile generalist. His eccentric musical patterns are as distinctive as any leitmotifs in the works of Hemingway or Fitzgerald.

For example, certain ranges and cadences of certain instruments appealed to Horner. He often employed the low rumblings of the piano to evoke suspense and danger. He used choruses and solo vocalists of different kinds to great effect. The shakuhachi flute, a Japanese woodwind, was a favorite of Horner’s. The instrument, capable of high-pitched blasts or low, driving rhythms, plays in Thunderheart, Legends of the Fall, Willow (1988), and The Mask of Zorro (1998).

James Horner adored the French horn. He wrote complex, melodic parts for it. He knew its capabilities so well that he wrote specific parts for specific players, knowing just who would do them justice. Horner utilized French horn for evocations of strength, nobility, and patriotism, but also for less common emotional filmic purposes: longing, anxiety, and even romance. Jenny’s theme in The Rocketeer (1991) exemplifies the soulful yearning that the high range of the instrument can project. In the “Preparations for Battle” cue in Glory, the French horn voices the solemn contemplation of soldiers before they storm Fort Wagner. The instrument speaks as eloquently of Union sacrifice as any speech by Abraham Lincoln.

Perhaps the most endearing and inspiring thematic trademark in Horner’s film music is his sympathy for the voyager. At sea, in the clouds, in space, Horner always found poetry in the journey. A lifelong aviator himself, he naturally allied with those charting undiscovered country.

A powerful current of heroism runs through his films with voyagers at their helm, such as Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), Titanic, The Perfect Storm (2000), Apollo 13, The Rocketeer, and Wolf Totem. Across different decades and directors, it recurs.

The Rocketeer, for example, is a tale of a daredevil with a rocket pack—well-suited for Horner’s strengths. The music revels in high-speed maneuvers high above the earthly bustle of humanity. The film’s end titles culminate in probably the fastest, loudest, most thrilling orchestral finale in Horner’s career. The music spits sparks and begs for replay.

Titanic and The Perfect Storm capture the joy of leaving harbor for the open sea, undaunted by whatever perils lie ahead. The “Leaving Port” cue from Titanic is an ode to the ship’s marvelous metalwork and pioneering skippers.

Horner’s explorer heroes include those lost in the avenues of the genius mind—in films like Sneakers (1992), Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993), and A Beautiful Mind (2001). “A Kaleidoscope of Mathematics,” a cue from A Beautiful Mind, conveys the elegance of mathematician John Nash’s solutions.

The score to Apollo 13 is perhaps the finest example of Horner’s questing orchestral spirit. During the ten minute cue for the rocket launch sequence, Horner’s grin is visible in the music. The music compacts all the exhilaration of the countdown. Just when the tension peaks, the orchestra explodes like the rocket at ignition. The Apollo crew soars to notes of Americana, innocence, and power.

The launch sequence is a landmark in film music history, as important as John Williams’ Star Wars theme and Jerry Goldsmith’s Star Trek theme. During this brief musical moment, hope seems to have the force of gravity. Such is James Horner’s magic.

It is a time to mourn the music that will never come. It is a time to rejoice in the music that exists. It is a time to reflect on Horner’s many compositions for odysseys into the unknown, where pilots light their way with courage and imagination.