Remembering the Man on the Moon: The Passing of Neil Armstrong

It should surprise no one, and yet, the passing of the first man on the moon enabled space – and the American way of life – to be yanked into the public fold with a degree of hubris that should turn any human off extra-terrestrial missions. Tributes are flooding various forums, extolling Armstrong as human, humane and gifted. These invariably leave out as much as they tell. Personal reminiscences of the man have been effusive, which demonstrates that cardinal rule that he who says little in public life shall have much spouted about him.

Like a vessel, he can be filled with speculative graces. There have been “celebrity reactions” – rapper Snoop Dogg was happy to tweet “RIP to my Unk Neil Armstrong! Stay High.” The scientific fraternity have also been forward about admiring, as physicist Brian Cox did, “the greatest of human achievements. For once, we reached beyond our grasp.”

Less conspicuous in the tribute train has been remembering the Apollo mission and the placing of a man on the moon as a political, even parochial gesture. Space, as other frontiers of human exploration, has simply provided another theatre of competitive exploration (read conquest).

In the eighteenth century, it was the struggle over who would have the right to control Australasia that dominated French and British “science.” The study of flora and fauna was hardly a separate enterprise from nationalist pride. Conquest and the sciences were one and the same thing.

There have been a few comparative notes on the subject of the Apollo mission as a modern, lunar version of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. What is interesting is the almost naïve sense that Armstrong rationalised his task. Exploration is de-fanged of its colonial and nationalist pretensions. It is simply boyish and dangerous adventure. And what of those comments that returning to the moon was daft? “It would be,” wrote Armstrong to Robert Krulwich of NPR “as if 16th century monarchs proclaimed that, ‘we need not go to the New World, we have already been there.’” The Indians might well have a point to make on that score, but no one is asking them.

Exploration, funded by state budgets, is very much a badge of national pride. John F. Kennedy’s science advisor Jerome Wiesner was terrified that a Soviet lead in space could signal the death knell to American leadership. Chinks in the armour of American supremacy had already appeared on October 4, 1957, when Sputnik 1, the Soviet Union’s esteemed satellite, was propelled into space. The President was keen to avert “a hostile flag of conquest” – the space banner would, instead, be one of “freedom and peace.”

By 1969, Americans found it appealing to look to space rather than the ramblings of earthbound existence. The Vietnam War was proving to be a bloody, stymieing affair. American towns were burning in the wake of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. With Soviet scientific triumphs, Kennedy made funding NASA programs a top consideration. The panic buttons proved costly – putting a man on the moon was an expensive and deadly exercise. The 1970 deadline was the albatross around the neck of the establishment, so much so it probably cost the lives of three astronauts on January 27, 1967 in the Apollo 2 disaster.

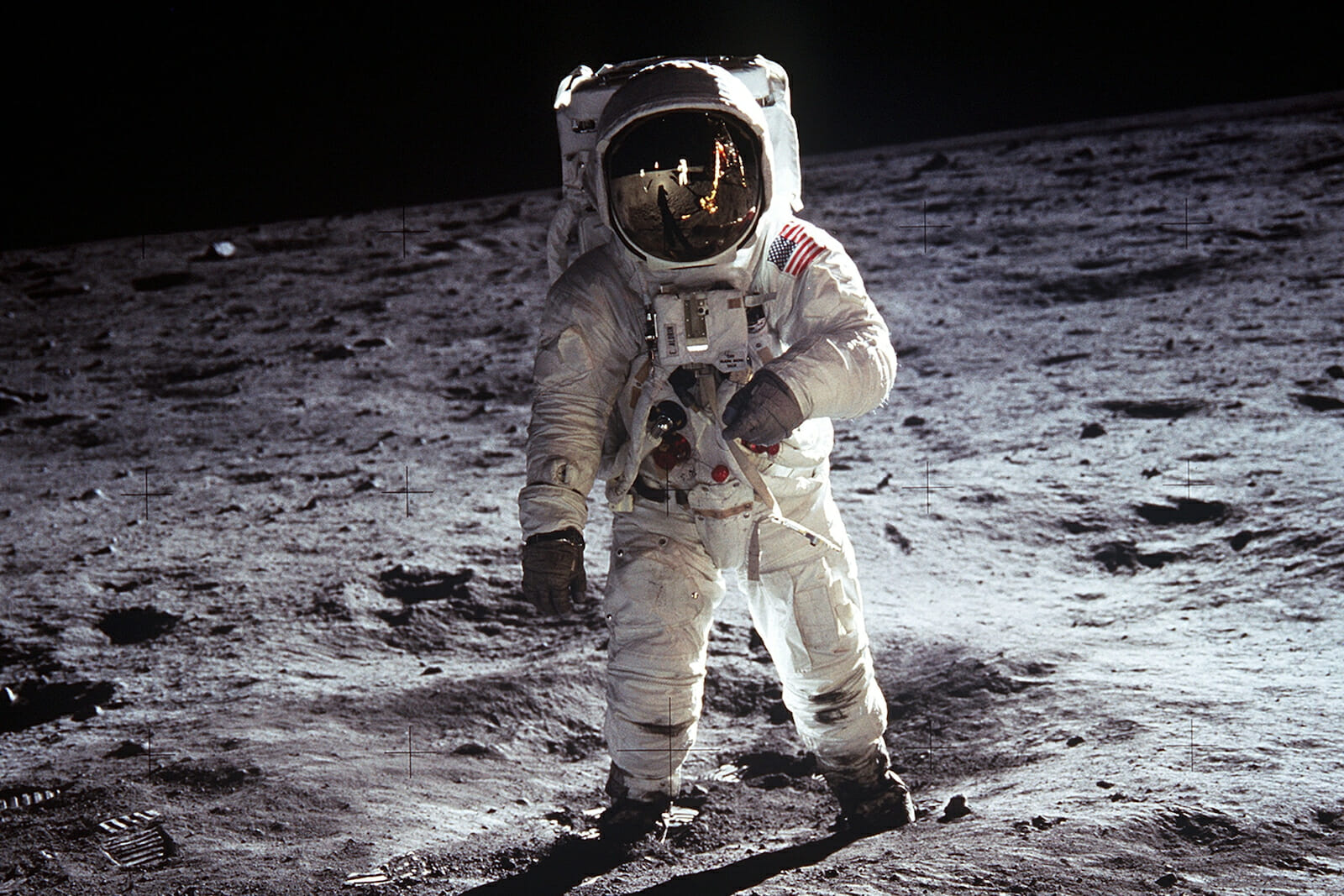

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong announced to Mission control that the Apollo II lunar module had landed on the moon. “Houston, Tranquillity Base here, the Eagle has landed.”

Armstrong himself never shied away from the motif of America the leader, taking the propaganda stand when he felt it was appropriate to do so. Glossing the rhetoric of space exploration with human worth could hardly conceal the fact that an American in space was a better option than anybody else, even for someone as “humble” as Armstrong. (Witness, in recent weeks, the gushing triumphalism of the NASA Curiosity mission on Mars.) The accent of humanity would have to be American, larded with good doses of freedom.

With the fiscal scythe beckoning for NASA in 2010, the Cold War space veterans were irked. What was this nonsense, they claimed, about the White House canceling the Constellation program, its Ares 1 and Ares V rockets, and the Orion spacecraft? The tone of baffled anger is all too clear in a co-authored open letter by Armstrong, James Lovell and Eugene Cernanin. This was Team America prowess more than anything else, a case of inspirational Pilgrims commanding their Mayflower into a new world.

During President Eisenhower’s first term, the authors write in the manner of shrill and scolding school teachers, “the Soviet Union excelled.” Subsequent presidents had “bold vision” – “we rapidly closed the gap in the final third of the 20th century, and became the world leader in space exploration.” Space exploration motivated the young, created global technologies, forged the brand “American made.” “For the United States, the leading space faring nation for nearly half a century, to be without carriage to low Earth orbit and with no human exploration capability to go beyond Earth orbit for an indeterminate period of time into the future, destines our nation to become one of the second or even third rate stature.”

So, the passing of Armstrong enables us to reflect not merely on the folly of primeval moon politics but the generally sinister disposition any talk on space travel tends to take. Is it impossible to divorce the landing from the German expatriate scientist Werner von Braun, who not merely built the lethal rockets that would come in rather handy in the Cold War, but used, during World War II, abundant sources of slave labour in the bargain. That’s progress. The flight trajectories to space are littered with human corpses and delusional patriotism – but don’t tell the space hagiographers that.