Books

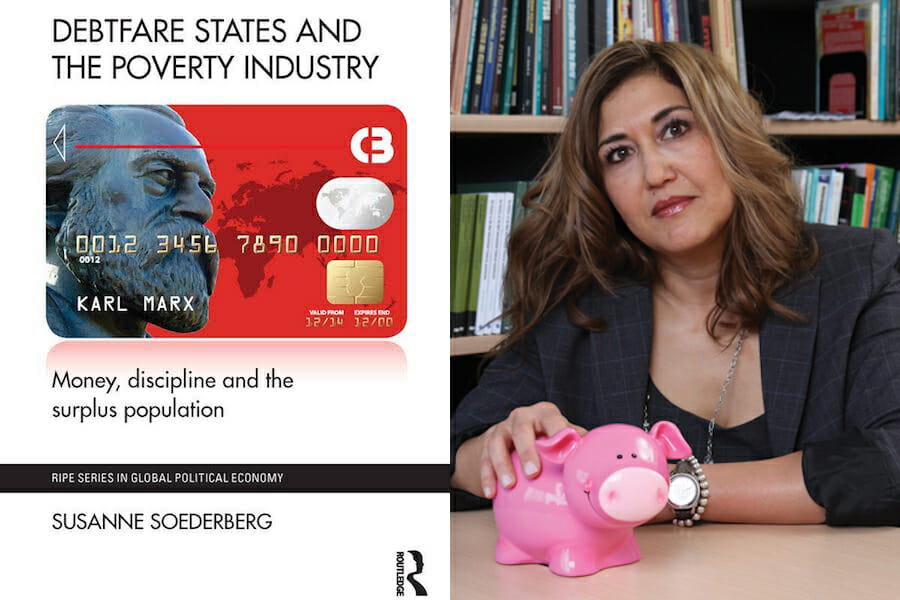

Review: ‘Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry’

Productivity is the driving force behind a nation’s financial recovery, particularly for advanced economies, for when output is increased standards rise and the public sector has higher tax receipts to cover debts as well as expend services. In recent years anemic growth and record unemployment has stymied most economies, leading to calls for more job creation to permeate political discourse around the world; however, a seemingly missed concept is that not just any job will do.

There are many reasons for slowed economic recoveries but the most prominent is the loss of the middle-class which has traditionally shored up struggling economies through consumer spending. In the current environment, the middle-class has been hindered by stagnating real wages, unemployment and underemployment, as well as rising consumer debt, which has become a necessary financial impediment being utilized to purchase necessities such as food, clothing, and healthcare.

Increased consumer credit and high interest rates have depressed middle-class households to such a degree that it is damaging a nation’s social fabric by increasing the prevalence of inequality which, in turn, restrains national economic growth.

Under the current economic paradigm, debt accumulation is being utilized as a stopgap to circumvent marginalization – consumer credit provides households the ability to mask inequality through consumption, financed by debt accumulation.

In her most recent work, entitled Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry, Susanne Soederberg delves into the illusion of financial inclusion and “the societal structures and processes that have normalized and naturalized the reality of pervasive debt, or what [she] refer[s] to as debtfare.” Researching the implications on how the “reliance on credit” has been used to “augment and/or replace the living wage” she has rightly exposed not only how society has become dependent on consumer credit, but also the “social machinations involved in…normalising, depoliticising, legitimating – the social necessities that compel the working poor to depend on credit” to ensure their livelihoods.

Her research generates succinct yet comprehensive coverage of the overall impact of debtfarism and how the poverty industry is pervasive in the United States and Mexico – two countries she assessed in six case studies which examine the societal impact of debt, individually, and “the cross-cutting relational factors of the [poverty] industry writ large.”

Moreover, she explains how privately created money – consumer credit – has been generated to replace real money under the guise of social inclusion, yet, in reality, credit only integrates “the surplus population into the capitalist system…as debtors.”

In one case study, the student loan debt of the United States is placed under a microscope and scrutinized for its attempt to mask the underlying structural problem of the rising cost of higher education, the manipulative nature of the industry, and pervasive unemployment and underemployment that awaits most graduates. The student loan crisis has inadvertently constructed a social experiment in which the United States’ future generations are entering the world with a negative net worth, which most in the loan industry believe will correct itself over the long-term as the graduate’s lifetime earnings will more than cover the initial costs of higher education. It is an experiment with an uncertain and unknown future.

The debts accumulated in higher education greatly impact a nation’s economy because the youngest generation is forced to exist on a lower income than previous ones, causing them to struggle to finance key national economic drivers – such as real estate – due to reduced household purchasing power. With increased demand for a college-educated workforce, this generation must gamble their financial security to make headway in the current market. For most, gone are the days where a summer of employment could finance an entire year of college tuition; today’s generation is saddled with the reality of low wages, high tuition costs, and ever-increasing cost of living.

Pervasive debt does not solely impede the holder; it generates risk throughout an economy: “Consumer credit cannot escape the fact that it operates as a fictitious value and continually threatens the stability of capital accumulation by gambling on the debtors to repay their loans. If this gap widens too far it threatens the quality of real money, with the potential for a crisis to ensue. Since it is vital to protect the quality of (real) money to ensure its social power as the universal equivalent, capitalists created consumer credit to absorb these tensions.”

Selling debt to lower- and middle-class households creates an environment ripe for exploitation. Businesses are protected by the state to implement programs that would loan money to poorer individuals at greatly increased interest rates, thus creating a debt cycle that only a few will be able to break. Programs that create revolving debt risk a country’s medium- and long-term stability – sowing the seeds of inequality by saddling the poorest in society with large debts and high interest rates.

The inequality generated stresses class relations, as illustrated during the United States’ outcry over excessive executive pay and bonuses following the financial collapse. Though the disquiet has ebbed nothing has changed for many in the West; all the while financial institutions continue to break records. While those at the apex of the economic hierarchy continue to make money and strengthen corporate balance sheets, many people struggle to find adequate employment that not only pays a living wage but also provides them an opportunity to repay debts owed.

Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry is magnificent at encapsulating the issues surrounding the politics of debt, society’s reliance on consumer credit, and possesses the necessary questions to reexamine the parasitic nature of the current industrial structure.