Books

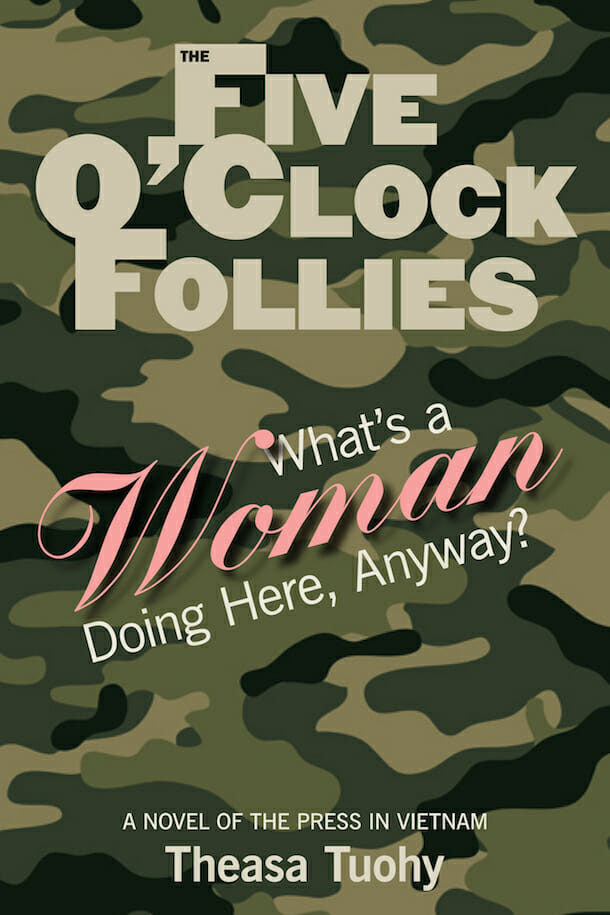

Review of Theasa Tuohy’s ‘The Five O’Clock Follies’

“Listen people, I don’t know how you expect to ever stop the war if you can’t sing any better than that. There’s about 300,000 of you fuckers out there. I want you to start singing. Come on.”

This isn’t the only song that sums up the Vietnam War but it’s one of the best sing alongs with its funny, yet despairing lyrics and catchy tune. Country Joe’s “recruiting” song is pitched to big strong young men, students, potential American soldiers, even though he can’t give them a good reason as to why they should be willing to die in Vietnam – in fact, as he says, “don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn.”

Country Joe names the prime movers of the war and they are not patriots – they’re big defense contractors cranking out profitable weaponry to kill the Vietcong. Patriotism is the final refuge of the scoundrels here – the brute military patriotism that can’t wait to blow all the commies (slants, dinks, pick your crude moniker) to kingdom come. The pearly gates of Heaven are doing excellent business.

So what would a young, attractive, talented American woman be doing in this very male, testosterone ridden erratic terrifyingly violent environment? And in the 1960’s, which was a harbinger of change for women in many professional fields but perhaps less so in journalism. Journalism was relatively slow to welcome women (although one can mention 5 or 6 extraordinary women, predecessors of Five O’clock Follies’ heroine Angela Martinelli, including one woman who was paid the ultimate compliment: she had become one with the grunts). How may we, who can now turn on the tube and see scores of women correspondents, even on the battlefields, understand the magnitude of this barely fictionalized but very real woman’s accomplishments?

Well, it makes for a great story! And although Tuohy does not push this point, the character, Angela, has many traits in common with Tuohy herself, including innovation and determination – and the fact that she is breaking Saigon’s glass ceiling for women correspondents.

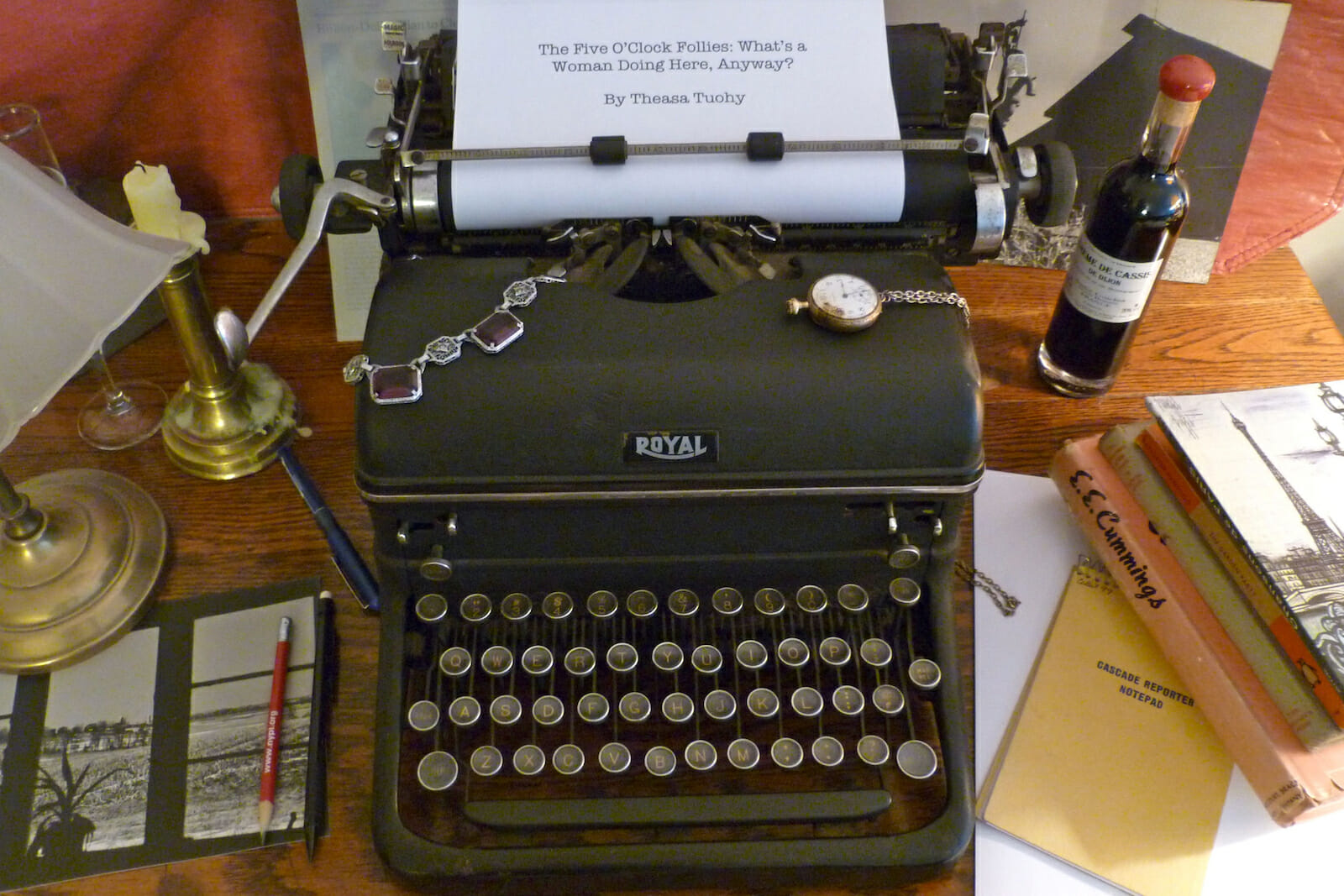

Touhy, the first female Assistant City Editor at The Detroit News, was confronted daily with the need to compete along with ambitious young male reporters. The Five O’clock Follies was undoubtedly inspired by this struggle. The struggle begins as the heroine Angela Martinelli arrives in Vietnam in a dress and sexy transparent heels, which cause admiring and derisive commentary from the guys, some of whom later become her friends. She soon sheds the heels for combat boots.

Angela is a complex highly intelligent blue blood character – she is given traits that are both traditionally feminine and masculine. On the feminine side yes, she occasionally weeps in crisis but wipes her eyes, gets up and gets going. She appears to be ruled by her emotions as she seesaws between two compelling men, one of whom she almost marries. She has been known to wear a dress at a fancy Embassy function but is more likely to be seen in camos.

But she is also far more likely to take on a traditionally “masculine” role – she is capable, trained, determined and competitive, she can be wounded in action and continue to work and help tend her fellow wounded even as she slowly mends, she can drink, and banter with her male counterparts, incidentally picking up scuttlebutt, the heart and soul of a reporter’s “down time.” She gets captured by the Vietcong, and is, amazingly, able to hang out and banter with them too, and is able to tell the story to American journals; and perhaps most importantly, she rounds out the tales of her Vietnam reportage with a story that is critical and that has appeared nowhere else in print- a story of malfunctioning American choppers which crash midflight causing far too many deaths.

We experience what she endured and increase our depth of understanding of the pull of this war and of Vietnam. The correspondents are sometimes able simply to distance themselves, to treat it as backdrop- to hold rooftop parties and “watch the war”—the lights, the combat. It is all so compelling that as the Vietnam War winds down and Cambodia winds up, even though she has just made plans to return to the US and to marry one of her suitors, Angela changes course. She feels obsessively driven to stay in country and cover the next war. “It’s Cambodia,” she pleads to her lover Ford. He says sadly, “There will always be another Cambodia” (and – understood – Angela will always want to be in Cambodia and not in a New England kitchen wielding a spatula).

As many have said, the amazing thing about this book is that it feels so real – more like creative nonfiction or a memoir – and yet it is nonfiction. The author did not actually serve in Vietnam but you wouldn’t know it. She researched the country and the people in intense detail so that we see the lovely young Vietnamese ladies with their elbow length white gloves, the 5-person families tottering on a single bicycle; we can almost smell the gangrene and ubiquitous pho beef soup; we clutch to handholds as the choppers pitch and yaw.

To give readers this sense of intense reality, Tuohy did extensive research, creating a novel that not only accurately depicts what life was like for reporters stationed in Vietnam, but also immerses the reader in the war that surrounded them. She writes from the perspective of the correspondents, and she is also close to the lives of the grunts – the adrenaline, pain, the dirt, the relentless rock and roll.

In a recent interview, Tuohy spoke of the reason for her choice of Vietnam for a setting; of her archival research on Vietnam; of her start as a journalist, and on the possible relevance of her book to today’s journalists.

When asked “Why Vietnam,” Tuohy says that her writing about Viet Nam dates back to 1966 as a cub reporter in Yonkers – about Second Lieutenant Francis Michael Doyle from Yonkers, his death in the Vietnam conflict and his UN memorial site. “An altar boy comes home from the war—a soft echo of the explosive war in Viet Nam.” Tuohy: “I suddenly remembered crying when I wrote it, crying at the gravesite. “ Doyle may have been the germ of this book.

Since that time, Touhy says of her archival research on Vietnam: “Work on this project began when I was working for the Op Ed page at Newsday and found a book called Big Story in the slush pile. It was a…study by Peter Braestrup with the subtitle ‘How the American Press and Television Reported and Interpreted the Crisis of Tet 1968 in Vietnam and Washington.’ I can still remember sitting up in bed that first night and studying it, mainly the 1968 map of central Saigon with locations of all of the press offices marked. I take pride in the fact that the book is historically accurate, in terms of the dates, battles, and what life was like. Or as Hemingway once said: ‘And how the weather was.’ I traveled to Vietnam in 2003 to double check my research and pick up what writers term ‘the telling detail.’ I made a point of staying on the second floor of the Continental Hotel, where the hotel claims that Graham Greene lived when he was writing The Quiet American.

She shares it with me – Big Story (it is indeed big)- and explains that both the maps and the text are so detailed, that she was able to construct the cities of Vietnam as exactly as possible and plot the movements of her characters through them. I feel I am in a newsreel, or more accurately, I feel I am there and can see smell and taste the country on all sides as we move. It is utterly convincing.

The book is a lifelong project. In other news, Tuohy is of course a journalist. Tuohy says of her start as a journalist: “After I took my last final at Berkeley, I got on a train for New York. Before I landed my first newspaper job, I did a short stint at Seventeen Magazine. I wrote briefly for a children’s encyclopedia, attended law school for four days, worked at Macy’s as a store detective for one day and travelled in Europe a couple of summers, once on a freighter. I was thus prepared to do whatever struck me, so I paid no attention when men at newspapers wondered what a woman was doing there. I had a fun job I was trying to learn, and I loved the slapdash and unpredictability of each new day. The only real preparation I made towards the future was that I refused to take a shorthand course, even when I was repeatedly warned that as a woman I’d need something to fall back on.”

Tuohy’s comments on the relevance of the Five O’clock Follies for today: “We’re still in unpopular distant wars. Women journalists are around in increasing numbers, and paying the price such as American journalist Marie Colvin of the London Sunday Times who was killed in Syria in February. With women now being allowed to be killed, raped and shot at along with the men, it will probably come as a surprise to many young women today to find out how different it was not so very long ago. I guess this is progress?”