Somalia: The Media, Resources & Ethnic Conflict

Fighting amongst neighboring peoples has been endemic throughout the history of humanity. From biblical clashes in Assyria to the civil war raging in Syria today, there is always turmoil brewing between two or more rival ethnic groups. They can take the form of prolonged struggles or they can seemingly crop up out of nowhere. However, no social breakdown happens for no reason. The two-decade long conflict in Somalia can be explained by instrumentalism.

Instrumentalism is a theory that posits that politicians and the media play a paramount role in the formation of ethnic identity and rivalry. Rulers inculcate ethnic values into its citizens starting from birth. Children are educated with curriculums that are tailor-made to complement the government’s view of history. Television programs, radio shows, web sites, music, plays and books are commissioned by politicians or, in industrialized nations, by business interests to support their agendas.

The People’s Republic of China is a textbook example. They censor anything in their history books or websites that is damaging to the legitimacy of the regime, like anything having to do with the Tiananmen Square Massacre. If resources (water, food, grazing land, minerals, metals, oil, etc.) are becoming scarce in an area, the local leader might incite ethnic violence towards a neighboring group in an attempt to redistribute scarcities to his people. An ambitious leader could likewise invoke ethnic hatred in order to expand his territory. Such a power play amongst the monarchs in Europe resulted in World War I.

Rulers often mask their true intentions by using existential rhetoric. They argue that the rival ethnic group must be exterminated in order for the favored ethnic group to enjoy lasting prosperity.

From the near-elimination of Native Americans by the US Army to the Hutu Power movement in Rwanda and Burundi, leaders have successfully utilized fear-mongering tactics to mobilize their people against enemies.

Somalia is a textbook case of instrumentalism at work. Somalia’s clan leaders foster ethnic feuds against each other so that they can fight for scant resources in their incredibly impoverished land. There is little fresh water and arable land in Somalia. As a result, most of its population has to rely upon agro-pastoralism for sustenance. Somalia’s ubiquitous goat herders must constantly search for grazing land to support their herds. This frequently leads to conflicts with herders from rival clans. Thus, there is perpetual animosity between neighboring groups, who must ensure that they have the land to support their main source of nutrition. Warlords arise to fight for their constituents. They must also scuffle over the few profitable metals and minerals buried in the country to help subsidize their living conditions. The fall of Communism in both Somalia and Russia brought about an end to Somalia’s international relevance.

The USSR, China and the United States had at various points heavily financed Siad Barre’s regime. After the Kremlin jilted Somalia in favor of its newly Communist neighbor Ethiopia, the US and PRC started supporting Barre’s nation to undermine the former. The Communist, and later Western, camaraderie kept Somalia from going hungry, which kept the various clans placated. After the Cold War ended, the political empires left Somalia. Siad Barre found that he had no allies left and the country quickly plummeted into poverty. Clans took up arms to fight for whatever resources were left, ousting the now bankrupt dictator and ushering in an era of anarchy. The more prosperous north eschewed fighting by creating a narrative of unity, leading to the creation of Puntland and Somaliland.

Political leaders have been using ethnicity to unite and divide Africa for centuries. During the scramble for Africa, the European colonial governments explicitly exploited this dichotomy by dividing and conquering. By pitting your rivals against each other, they become much easier to deal with. The imperialist puppet states fostered an environment of us versus them so that the native peoples would fight each other instead of the new foreign-helmed governments. Uprisings against colonialism inevitably failed as a result: they were too disparate. To overthrow a government, there needs to be broad support from the citizenry.

This points to a fundamental weakness of revolutionary movements: they are always up against opponents with superior organization, media connections, money and manpower. The Europeans had far superior military might, logistics and experience. More importantly, they controlled the media and thus the public mindset. When an uprising would sprout, the colonialists would do their best to sweep it under the rug before it could gain traction. They were able to mobilize quickly against hostilities through their modern communications technology. The few modern media resources the natives had access to, such as newspapers, were controlled by the government and thus were whitewashed to favor the status quo.

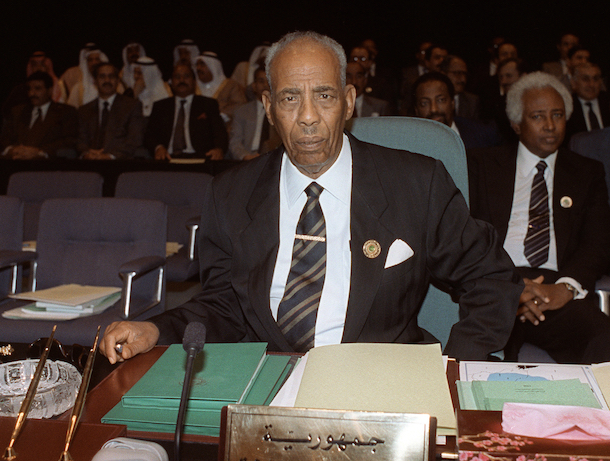

Somalia has similarly dealt with media brainwashing, even post-independence. Mohammad Siad Barre created a personality cult, wherein he was deified as a Communist god. His official title was “Guulwaadde,” the Victorious Leader. Siad Barre constantly boasted about having united the various tribes of Somalia under the banner of “Scientific Socialism.” He was no doubt inspired in this respect by one of his initial allies, Joseph Stalin. Like Stalin, he also loved to have portraits of himself in the public squares and during parades being carried alongside those of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. Siad Barre also brutally oppressed anyone who publicly opposed him. By torturing and killing his dissidents, he was able to control the national narrative throughout his rule.

After suffering a crippling military defeat trying to invade the ethnically Somali Ogaden region in Soviet-backed Ethiopia, Siad Barre had to swallow a lot of his ethnic unification rhetoric. The other clans began to doubt his leadership capabilities, as well as his promises of a “Greater Somalia” union. He began to rely heavily on the Marehaan, his native tribe, for political and military support. People began to secretly refer to the government as “MOD,” an acronym for the Marehaan, the Ogaden (the tribe of Siad Barre’s mother) and the Dulbahante (the tribe of Siad Barre’s son-in-law and an important colonel in his army). Towards the end of Siad Barre’s regime, he took a page out of Saddam Hussein’s playbook and began attacking villages of rival clans. Livestock were slaughtered and wells were poisoned, literally starving the opposition. He infamously bombed the city of Hargeisa to the ground in 1988. Unsurprisingly, the rebuilt Hargeisa is now the capital of separatist Somaliland.

Siad Barre’s hypocritical approach to handling his nation’s diversity points firmly to the tenets of instrumentalism. He used the narrative of national unity when it suited him. When faced with opposition from clans other than his own, he began to switch the official discourse to face the problem. Instrumental was Siad Barre in determining how the peoples of Somalia viewed and behaved towards one another. The purging of disparate tribes late in his regime would set the tone for the nation after his overthrow in 1991. The entire nation split upon ethnic lines, driven further and further apart by fighting in the power vacuum.

Currently, no one has firm control of the fledgling Somali media. There are few newspapers, radio broadcasts and television shows aired in Somalia due to the deep infrastructural damage major facilities incurred during the two-decade long civil war. Financing media ventures is another issue in the impoverished nation. Foreign donors are very hesitant to inject any money into projects in the country, due to the danger and corruption. They would be wary of accidentally funding the Islamic insurgency, which funnels a lot of money that enters the country. Thus, there is no dominant narrative in Somalia. This perpetuates the civil strife in the country. Citizens inevitably coalesce towards their local warlords or international terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS for guidance. Without a national narrative, there can be no reasonable chance for reconciliation. Differing peoples need to hear from the other national perspectives to be properly informed about the issues of the day and fair solutions for all.