Can Autonomous Vehicles Ever Be Truly Safe?

With any new technology, especially one involving autonomous vehicles, there are significant safety issues to consider.

For decades, the promise of autonomous vehicles was cast in near-utopian terms: roads free of human error, cities without traffic, and a dramatic decline in fatalities. That vision collides with a far messier reality when automated systems fail. For more than a century, accident causation has been overwhelmingly attributed to human error, and our legal regimes have been built around this certainty. Now culpability is shifting—from the person behind the wheel to the lines of code that govern the machine. Technology can reduce risk, but it cannot, by itself, resolve the crisis of accountability.

The central obstacle to safe, widespread AV adoption isn’t hardware or software; it’s a legal and ethical vacuum. Without a clear, internationally coherent answer to who pays—and who is responsible—when an algorithmic decision results in injury or death, the driverless future remains stalled by unresolved questions of justice and liability.

When the “Driver” Is an Algorithm

Tort law has governed crash disputes for generations by locating a human mistake—distraction, impairment, or negligence. That doctrine now faces an existential test. In a Level 5 vehicle with no human driver, the very notion of a negligent motorist dissolves. Even with advanced driver-assistance systems, the technology can lull operators into complacency, blurring the lines between operator responsibility and system control. Courts around the world are grappling with the mismatch. Some jurisdictions, including the Philippines, still attempt to retrofit old rules—such as holding the vehicle’s registered owner liable for any incident—an approach that fails to address the role of the manufacturer, software developer, or sensor supplier whose system made the decisive call.

A Patchwork That Pleases No One

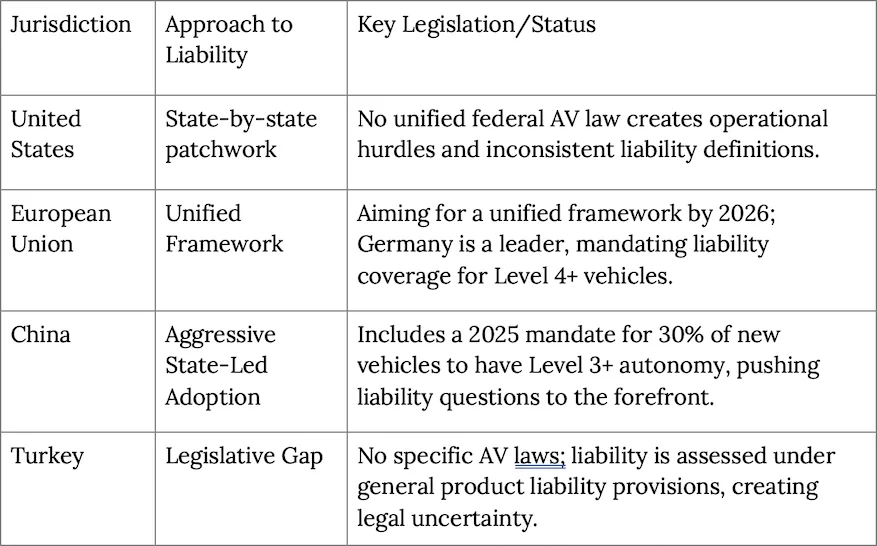

The global industry only compounds the problem. The United States has no unified federal statute governing AVs, leaving a tangle of uneven state laws that create operational headaches for companies and confusion for victims about who can be sued—and where. The European Union, by contrast, is aiming to establish a coordinated framework by 2026. Germany has taken the lead, amending its Road Traffic Act to maintain strict liability for the vehicle’s operator even when automation is engaged. China pairs aggressive deployment with a heavy state hand, Taiwan uses sandbox trials, and Turkey lacks a bespoke regime, leaving courts to stretch general product-liability doctrines to fit novel facts. The result is a regulatory patchwork that risks undermining both safety and innovation.

From the Driver’s Seat to the Boardroom

Recent Tesla litigation provides an early indication of where accountability may lie. For years, Tesla maintained that the human driver bore ultimate responsibility. But a series of 2025 verdicts is eroding that defense. In Benavides v. Tesla, a Florida jury found the company 33 percent liable for a 2019 Autopilot-related fatality—one of the first successful third-party claims linking corporate design and marketing to a non-occupant death. The jury concluded that Tesla’s design and messaging fostered a false sense of security that contributed to driver inattention. That fits a broader pattern: the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has documented more than 950 Autopilot-involved crashes since 2018, evidence that the problem isn’t a series of isolated drivers but a system-level risk.

The Human Cost of Machine Mistakes

These failures are not abstractions. High-speed automation errors often translate into catastrophic injuries, especially traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). In the United States, roughly 190 TBI-related deaths occur every day, and survivors can face lifetime costs that exceed $1.8 million. When an AV crash produces such harm, who absorbs those costs—the carmaker, the software vendor, the sensor supplier, the connectivity provider? The dense supply chains behind AI systems create a serious risk of an “accountability gap,” as the Law Commission of England and Wales has warned, where each actor points to another and no one is held accountable.

Why Expert Litigation Matters

Untangling responsibility when an algorithm is at fault requires more than a standard accident reconstruction. It demands deconstructing code pathways, sensor fusion logs, systems engineering choices, and corporate marketing claims—all while documenting the full, lifelong impact of injuries. That is where specialized counsel for catastrophic injuries becomes indispensable. Firms such as Richardson Richardson Boudreaux—established Tulsa brain injury lawyers—pair litigation strategy with teams of neuropsychologists, economists, and vocational experts to quantify damages and pierce the technical fog that can otherwise leave victims uncompensated. In a world where the “driver” may be non-human, methodical evidence development is the difference between an accountability gap and accountability.

Ethics, in Code

Legal debates are inextricably linked to moral ones. Philosophy students have grappled with the trolley problem for decades; AV engineers must operationalize a solution in milliseconds. Should an AV swerve to endanger one to save five? Prioritize occupants over pedestrians? These aren’t thought experiments once they’re hard-coded. Unsurprisingly, research shows that unresolved ethical questions—and regulatory ambiguity—are eroding public trust in AVs. Without a shared moral logic and transparent governance, adoption will lag.

Four Models on the Table

Policymakers are circling several complementary models to close the liability vacuum.

With strict product liability, manufacturers would be held responsible for harm caused by autonomous systems, regardless of their own fault. That shifts financial risk from consumers to corporations, incentivizing rigorous pre-market safety and ongoing monitoring. With no-fault compensation, governmental or industry-backed funds could promptly compensate victims of AV incidents, sparing families years of litigation over causation and fault while preserving the ability to pursue recourse against culpable parties.

With tiered liability by automation level, responsibility would track the SAE J3016 level active at the time of the crash—shared liability for Level 3 (where human fallback is expected), moving toward manufacturer-dominant liability for Levels 4 and 5. The final model will require every AV to carry a tamper-proof event data recorder that captures inputs, system state, and decision pathways. Without an auditable record, regulators and courts can’t reliably assign fault or improve safety.

The Path to Trust

Technology is racing ahead; the legal and ethical scaffolding is lagging. Courtroom verdicts—especially those scrutinizing design choices and marketing claims—are shifting accountability from individual drivers to corporate boards. But without coordinated national and international rules, victims of algorithmic error will fall through the cracks, and public confidence may harden into skepticism. The question is not whether roads will become automated—they already are—but whether we will build rules that protect human life before the code is universally deployed.