Media

Tagging Manipulated Media in a Polarized World

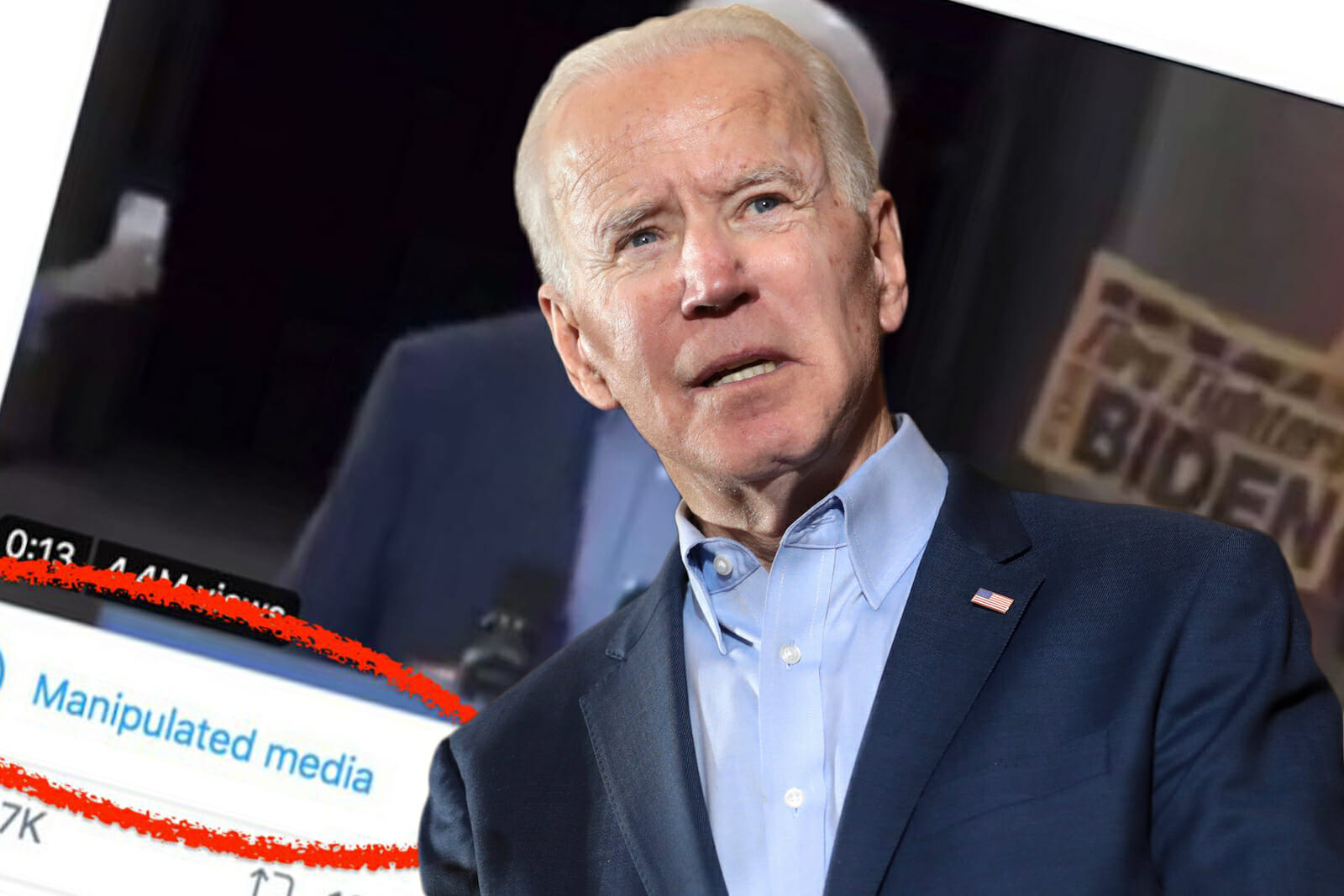

When the microblogging platform Twitter applied its “manipulated media” tag for the first time on 8 March 2020, it was on an edited video of a speech by former Vice President Joe Biden. The tag informs netizens when a photo or video has been “significantly altered or fabricated,” a more focused approach at targeting disputed visual-based content. While certainly a step forward, tackling the challenges of disinformation on social media remains an uphill battle.

For one, Twitter’s new initiative is aimed at anticipating future iterations of disinformation. Much has been made of the potentially disastrous impact of deepfakes, artificial intelligence-assisted video and audio editing for creating disinformation and sowing discord. From privacy breach to undermining public trust and even national security, the implications of deepfakes are limited only by the imaginations of certain actors.

While deepfakes are developing at a rapid pace and becoming available to netizens, it is too early to tell if it will become ubiquitous and thus have widespread implications in society. After all, the manipulation of photos, videos, and audio is not new. Photoshop, an image-editing tool, was introduced by Adobe in 1990. The only example of an application of a deepfake video in politics had been a Belgian Socialist Party’s campaign video showing Donald Trump urging the country to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement.

In fact, rather than experimenting with complex new technological tools, purveyors of disinformation may fall back on existing ones that are easier to deploy. As the first application of the “manipulated media” tag shows, simpler forms of disinformation are more pervasive, and at times cause more damage. For example, in Indonesia, former Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was convicted of blasphemy after a clipped video of him accusing his political opponents of using religion as a campaign tool was shared on Facebook in October 2016. The video of Biden had similarly been simply trimmed to remove key parts of the sentence. The net effect, which was to make him sound like he was endorsing Trump’s re-election, was still achieved. Technologically sophisticated tools like deepfakes are thus peripheral in the larger goal of disinformation.

Addressing the state of play in disinformation on social media platforms has been challenging. For some content that falls somewhere within the spectrum of falsehoods, social media companies have preferred to allow netizens to decide whether to trust the content or not. By tweaking their technological architecture, these companies have been able, to some extent, to control what they permit or dissuade on their platforms. For example, Facebook’s now-defunct “Disputed” tag aimed to inform the audience of the contested textual content. Instagram’s “False Information” label served the same function for images on the photo-sharing site.

Placing visual indicators like a red flag besides an article, however, tends to reinforce instead of change existing beliefs. This is because, in an environment of greater media choice, content preferences predict rather than shape beliefs, according to political scientist Markus Prior. Exposure to and interaction with content that affirms in-group identity thus serve to boost the identity while rejecting opposing ones. Polarization is particularly evident on social media, which is not designed for constructive interactions with those with a different viewpoint. In consideration of such a possibility of psychological reinforcement of existing beliefs, Facebook replaced its “Disputed” tag initiative with measures to provide greater context around contentious articles.

Addressing visual forms of disinformation faces the same challenges. As writer John Berger’s famous work “Ways of Seeing” noted, seeing is not mechanically reacting to stimuli, but an act of choice that is influenced by what we already know or believe. The efficacy of a “manipulated media” tag is therefore similarly suspect.

Posting the same visual content across different platforms also renders the tag less effective. Facebook, for example, did not tag Biden’s video as manipulated. Closed instant messaging platforms like WhatsApp, which is becoming a primary way in which many people around the world receive news and by extension, misinformation, are also not covered by the tag unless the receiver is directed to the Twitter post. Even so, Twitter is currently still working on fixing its user interface issue: the tag only shows up in the timeline view, not in the tweet detail.

As efforts such as placing legal and regulatory obligation onto technology companies and research into digital media forensics are underway, a measure that tackles the problem of visual-mediated disinformation from the cognitive aspect needs to be implemented. Emphasizing the visual and video literacy (the ability to understand and create visual and video messages) component in existing digital literacy efforts has become more pressing than ever.

Deepfakes or not, the fundamental interested/uninterested divide in the society will continue to be a challenge for technology companies and other stakeholders. It is time to move beyond the regulation of technological architecture to addressing societal divisions that influence how these technologies are used in the first place.