Tech

Tesla Marketing Says ‘Robot Chauffeur’; Legal Says ‘You’re Driving’

Elon Musk’s Tesla is awaiting judgment from the State of California in a case brought by the Department of Motor Vehicles, which accuses the company of the “deceptive practice” of misleading consumers about the capabilities of Full Self-Driving. The DMV contends that Tesla has marketed Full Self-Driving and Autopilot as autonomous systems when, in reality, the software requires a fully attentive human driver, ready to take over at a moment’s notice.

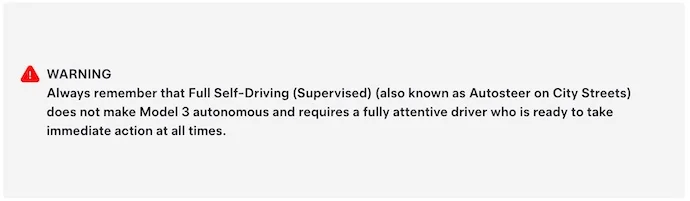

Tesla acknowledges this in the fine print. Buried in the owner’s manual is the quiet admission that FSD is not autonomous and that drivers must remain vigilant and prepared to act immediately at all times. Owners are effectively expected to hunt through hundreds of pages to find it.

The marketing tells a different story. For the past nine years, Tesla and Musk have persuaded consumers that “Full Self-Driving” lives up to the name. In 2016, Tesla released a video purporting to show a car driving itself from a home in Palo Alto to the company’s Silicon Valley headquarters, set to the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black.”

The marketing tells a different story. For the past nine years, Tesla and Musk have persuaded consumers that “Full Self-Driving” lives up to the name. In 2016, Tesla released a video purporting to show a car driving itself from a home in Palo Alto to the company’s Silicon Valley headquarters, set to the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black.”

When Musk posted the promotional video—“Full Self-Driving Hardware on All Teslas”—he asserted that the “Tesla drives itself (no human input at all) thru urban streets to highway to streets, then finds a parking spot.”

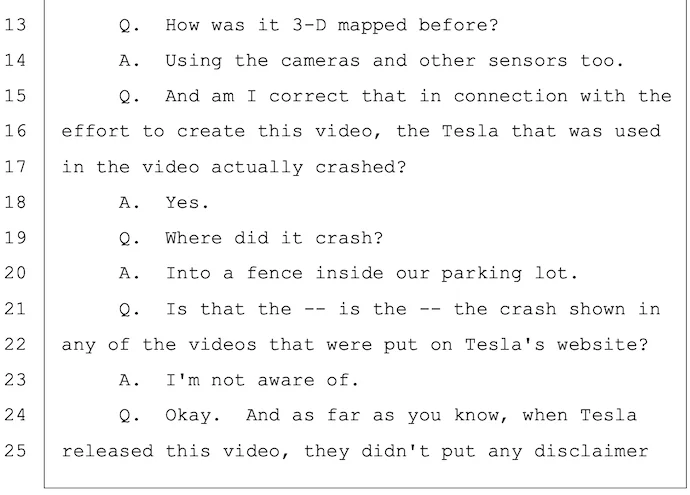

In July 2022, testimony from Tesla’s head of Autopilot, Ashok Elluswamy, showed how far the video strayed from reality. Under oath, Elluswamy acknowledged that during filming, the Model X crashed “into a fence inside our parking lot,” a glimpse behind the curtain at how manufactured the final advertisement was. He also said the video was staged and not an accurate depiction of Tesla’s capabilities at the time, despite Musk’s global claims that autonomy had been solved.

It also emerged that Musk personally directed the addition of a front card reading, “The person in the driver’s seat is only there for legal reasons. He is not doing anything. The car is driving itself.” Internally, he framed the video as a statement of what the car would one day do—not what it could do “upon receipt”—yet the card was crafted to imply the technology already existed, encouraging viewers to believe Tesla had built a fully autonomous system when it had not.

It also emerged that Musk personally directed the addition of a front card reading, “The person in the driver’s seat is only there for legal reasons. He is not doing anything. The car is driving itself.” Internally, he framed the video as a statement of what the car would one day do—not what it could do “upon receipt”—yet the card was crafted to imply the technology already existed, encouraging viewers to believe Tesla had built a fully autonomous system when it had not.

Even after these admissions, Musk continued to amplify the claim. In 2023, he suggested that people only “fully understand” FSD when they’re in the driver’s seat “but aren’t driving at all”—again implying hands-off autonomy despite knowing the system required supervision.

Even after these admissions, Musk continued to amplify the claim. In 2023, he suggested that people only “fully understand” FSD when they’re in the driver’s seat “but aren’t driving at all”—again implying hands-off autonomy despite knowing the system required supervision.

The gap between marketing and reality has had tragic consequences. In March 2018, Tesla owner Walter Huang died when his Model X hit a concrete barrier on US-101. A lawsuit filed by Huang’s estate in April 2019—eventually settled by Tesla—alleged that the company’s representations about Autopilot’s capabilities contributed to his death: “The Decedent reasonably believed the 2017 Tesla Model X vehicle was safer than a human-operated vehicle because of Defendant’s claimed technical superiority regarding the vehicle’s autopilot system.”

Tesla’s response was to place responsibility on Huang, saying he was distracted. Musk later told CBS News that Autopilot “worked as described,” adding, “it’s a hands-on system. It is not a self-driving system,” assigning sole blame to the driver.

Imagine if someone made a car that needed almost no maintenance, has the lowest repair costs of any brand & literally drives you anywhere with supervised full self-driving

We did

And they’re all S3XY

— Tesla (@Tesla) July 15, 2025

The pattern extends beyond autonomy claims. Tesla has also promoted the idea that its cars have vanishingly low maintenance and repair costs—all while hinting that the car “literally drives you anywhere with supervised full self-driving.” In practice, the picture is less rosy.

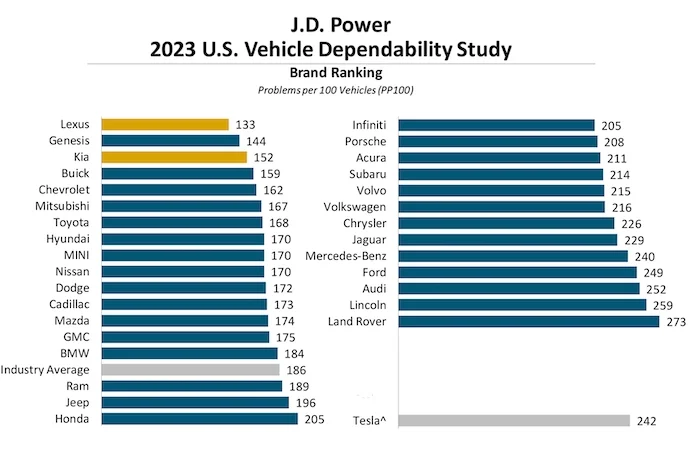

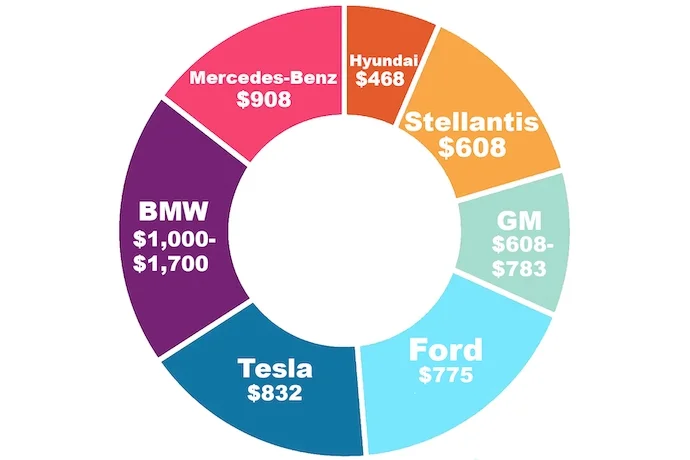

In J.D. Power’s 2023 vehicle dependability study, Tesla ranked well below the industry average. RepairPal, comparing average annual repair costs among top-selling brands, lists Tesla as the third most expensive—behind only Mercedes-Benz and BMW. Consumer Reports has likewise judged Tesla among the least reliable manufacturers, ranking it 19th out of 24, citing susceptibility to failures and uneven build quality.

The hype also misled corporate partners. In 2021, Hertz struck a splashy deal to lease 100,000 Teslas, positioning itself as a leader in EV rentals. By 2023, Hertz said it was restructuring its approach, citing higher-than-expected repair costs for its EV fleet—then mainly Teslas—which weighed on revenue.

Depreciation exacerbated the pain. As Tesla repeatedly cut prices, resale values slid. One reporter for CleanTechnica found a 42 percent depreciation over four years; a 2024 Fast Company analysis concluded the Model 3 and Model Y were among the year’s fastest-depreciating vehicles; and Electrek later reported that, by 2025, used Tesla prices were falling roughly three times faster than the broader used-car market. Hertz ultimately chose to unload its Teslas quickly to stem losses.

The promises kept not matching the outcomes. Tesla failed to deliver on pledges made in its promotional blitzes, leaving consumers, investors, and brand partners with expectations the company did not meet.

Instead of recalibrating, Tesla has, in recent months, escalated its language around FSD. The company now touts a “robot chauffeur,” says “your Tesla does all the driving,” and tells buyers the car will drive them—“not the other way around.”

For $99/month, your Tesla becomes your own @Robotaxi under your supervision

— Tesla (@Tesla) July 3, 2025

The messaging is sweeping: FSD will supposedly manage everything from route planning to the driving itself; driving without FSD will “feel like going back to the Dark Ages.” The pitch: “your Tesla takes you wherever you want, on its own.”

Tesla calls FSD a “robot car” and says its vehicles are “the only cars that can drive themselves anywhere.” For $99 a month, the company says, your Tesla can become “your own Robotaxi.”

Teslas can drive themselves! https://t.co/9TY6zgISh3

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) August 3, 2025

Musk regularly reinforces the point on X, declaring that “Teslas can drive themselves!” Even physical ads lean on the promise, tucking the word “Supervised” in tiny type next to “Full Self-Driving.”

A Tesla using Autopilot technology today is already 10x safer than the average US driver pic.twitter.com/uhEpDkVuNE

— Tesla (@Tesla) July 24, 2025

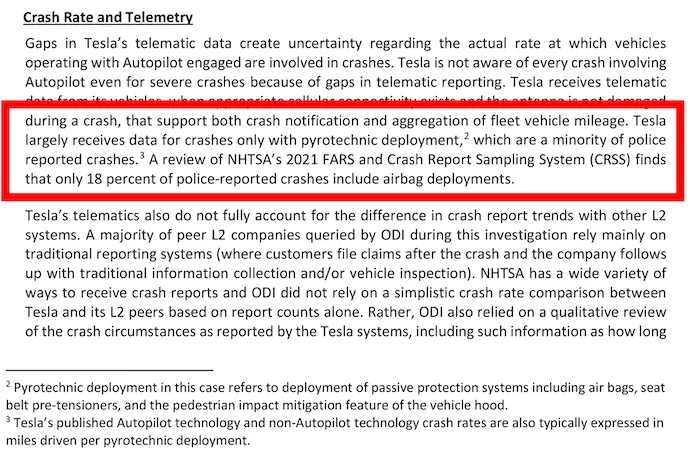

Tesla also claims its self-driving technology is 10 times safer than manual driving. But its comparisons count only Autopilot crashes that involve airbag deployments, while the U.S. average includes all police-reported accidents.

According to NHTSA data, only about 18 percent of police-reported crashes deploy airbags—meaning Tesla’s metric omits at least four out of five incidents when stacking itself against the national average.

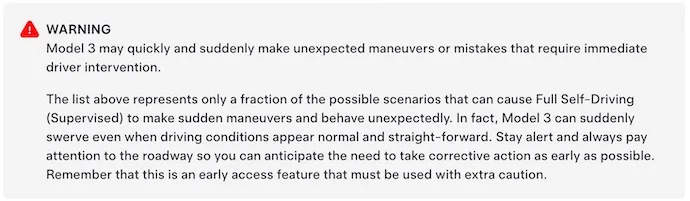

In court, however, Tesla leans hard on a different definition. When litigating FSD and Autopilot crashes, the company characterizes FSD as a Level 2 advanced driver-assistance system, comparable to adaptive cruise control, with the human driver ultimately responsible. Buried again in the owner’s manual is a telling warning: FSD “can suddenly swerve even when driving conditions appear normal and straight-forward.”

In court, however, Tesla leans hard on a different definition. When litigating FSD and Autopilot crashes, the company characterizes FSD as a Level 2 advanced driver-assistance system, comparable to adaptive cruise control, with the human driver ultimately responsible. Buried again in the owner’s manual is a telling warning: FSD “can suddenly swerve even when driving conditions appear normal and straight-forward.”

In 2021, Tesla told the California DMV that FSD was “still firmly in L2,” and it has likewise persuaded NHTSA to regulate the system as Level 2—keeping Tesla out of the stricter regimes that govern more advanced autonomous technologies. That regulatory posture—a “supervised” driver-assist system—sits awkwardly beside the company’s expansive consumer messaging about fully self-driving cars.

In 2021, Tesla told the California DMV that FSD was “still firmly in L2,” and it has likewise persuaded NHTSA to regulate the system as Level 2—keeping Tesla out of the stricter regimes that govern more advanced autonomous technologies. That regulatory posture—a “supervised” driver-assist system—sits awkwardly beside the company’s expansive consumer messaging about fully self-driving cars.

So FSD becomes a tale of two systems. In the showroom and on social media, Tesla courts safety-minded drivers with promises of an autonomous technology safer than humans. When crashes occur, the company points to the manual, invokes Level 2 caveats, and assigns fault to the person behind the wheel. In securities litigation, Musk’s more extravagant claims are minimized as “nonactionable statements of corporate puffery” that “no reasonable investor” would rely upon.

Musk and Tesla have repeatedly asked customers and investors to believe they are buying into autonomy while reserving, in legal and regulatory contexts, the right to say they are not.

That dissonance has real-world costs. It’s long past time to hold the company to its claims—and to the consequences of making them.