The Bitter Fruits of the Compromise of 1877

With the United States in turmoil over its history of treatment of African Americans, perhaps it should be made clear that the cause of the ingrained federal sanctioned racism against African Americans from 1877 to 1954 is the responsibility of the two major political parties in the United States. Since 1964, the Democratic Party has been a champion for African Americans. However, from 1877 to 1964, the Democratic Party was the main oppressor of this same population. Meanwhile, the Republican Party turned a blind eye to the overt and blatant racism that Black Americans suffered under Democratic Party policy and practice. The “re-enslavement” of African Americans in the South is the result of a bargain struck between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party in 1877 called the Compromise of 1877.

The Disputed 1876 Presidential Election

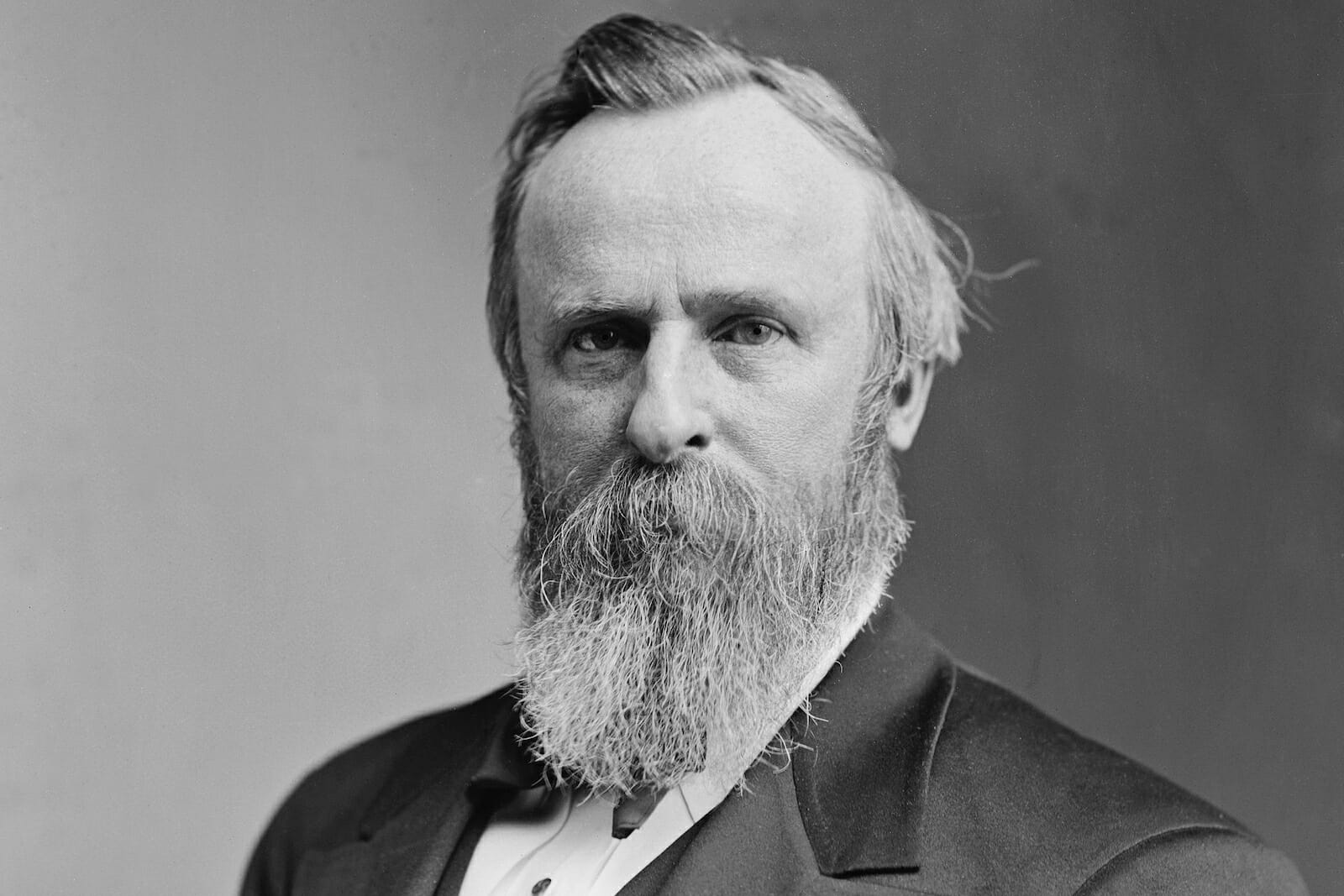

Despite pressure from Republican Party bosses and nationwide expectations, President Ulysses S. Grant did not run for a third presidential term in 1876. While Congressman James C. Blaine initially emerged as the frontrunner to succeed Grant, he was not able to secure enough votes to win the nomination. As a result, Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio was chosen as a compromise candidate. The Democratic Party nominated Governor Samuel J. Tilden of New York as their nominee.

The election of 1876 was one of the most controversial and contentious presidential elections in American history. There is no historical doubt that Governor Tilden won the popular vote by 254,000 votes. Prior to the Electoral Commission of 1877, Governor Tilden had 184 electoral votes, and his opponent Governor Hayes had 165 electoral votes. In dispute were 19 electoral votes from Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, and one elector in Oregon. Both parties presented their own electors and claimed that their candidate had won the presidential election of 1876. This precipitated a Constitutional Crisis.

The Electoral Commission of 1877

The Democratic Party controlled the House of Representatives, while the Republican Party controlled the Senate and the presidency. Both sides had the administrative power to block the other’s moves. In essence, the major political parties controlling the political life of the country were in a virtual standoff, threatening the polity of the United States.

In view of this stalemate, both parties agreed to establish an Electoral Commission to decide the election of 1876. The procedure for selecting a president in 1877 was different from the procedures that are followed today due to the 20th Amendment of the Constitution.

In 1876, Article Two, Section One, and Clause Three of the Constitution discussed the selection of a president and vice president in a disputed presidential election vastly different from today: “if no Person [has] a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in Like manner [choose] the President. But in [choosing] the President, the Votes shall be taken from States, the Representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two-thirds of the States, the Representation of each state having one Vote.”

Congressman James Monroe, a representative from Ohio’s 14th Congressional District wrote about the tension in the United States in an article in The Atlantic in 1893. In his article, he describes how violence was beginning to break out in the Halls of the House and Senate. This was the political backdrop of the Electoral Commission in 1877.

The Electoral Commission of 1877 reported back to the House and the Senate that along a party-line vote, a majority of the members of the Commission had selected Hayes as the winner of the presidential election of 1876, awarding him all 20 contested electoral votes. The Democratic Party immediately threatened to filibuster the process of selecting the winner of the 1876 presidential election, preventing a peaceful transfer of power. This is when influential members of the Republican Party and the Democratic Party met behind closed doors at the Wormley Hotel in Washington DC in February of 1877. This is where the Compromise of 1877 was struck.

The Compromise of 1877

The members of the Republican Party who met at the Wormley Hotel in 1877 were quite different from the radical members of the Republican Party who had controlled the GOP during and immediately after the Civil War. These members of the Republican Party were representing the interests of the men who were becoming increasingly wealthy with the rise of the railroads, and other members of the privileged elite who now controlled the GOP. These members were concerned about the Agrarian unrest in the West, as well as the labor unrest in the Northeastern parts of the United States, culminating in the Great Railroad Strike in July of 1877. While these men held control of the GOP, their control was tenuous at best, and they sensed an opportunity to acquire allies in the House and Senate with the Redeemer portion of the Democratic Party. In particular, they had gained the commitment of Governor Hayes to assist in the funding of the Texas-Pacific Railroad Company and supporting the business class over the labor unions. Federal funding for railroad construction had dried up with the Credit Mobilier of America scandal in 1872.

The men from the Democratic Party who gathered at the Wormley Hotel were distinct and separate from their fellow Democrats of the North. These men were from the Redeemer part of the Democratic Party. These men wanted subsidies from the federal government to help the South recover from the after-effects of the Civil War, while the members of the Democratic Party of the North opposed federal subsidies and had repeatedly blocked legislation granting subsidies in the House. The Redeemer’s also wanted an opportunity to recover the fortunes the Redeemer’s had lost during the war. These men were former plantation owners or representatives of the former plantation owners and the former elite of the South. They deployed a sense of anger at the loss of their slaves, their fortunes, and having been forced by federal troops to obey the dictates of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been established in 1865 to assist the newly freed American citizens.

Central to the demand of the Redeemer wing of the Democratic Party was the end of Reconstruction, the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, the promise by the Republican Party to end federal interference into the local political affairs of the South, federal funding for flood control on the major rivers of the South, and the funding of the Texas & Pacific Railroad Company. The GOP wanted assistance in controlling labor unions, help in putting down the unrest in the West as well as preventing a filibuster challenging the Electoral Commission’s findings. Governor Hayes’ representative was his trusted aide Charles Foster with the Tilden side being represented by John Young Brown.

This agreement was not put in writing but was described by Vern C. Woodward in his book Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction:

- The removal of all remaining U.S. military forces from the former Confederate states. At the time, U.S. troops remained in only Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, but the Compromise of 1877 completed their withdrawal from the region.

- The appointment of at least one Southern Democrat to Hayes’ cabinet. (David M. Key of Tennessee was appointed as Postmaster General).

- The construction of another transcontinental railroad using the Texas and Pacific in the South (this had been part of the “Scott Plan,” proposed by Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad; he had initiated negotiations resulting in the final compromise).

- Legislation to help industrialize the South and restore its economy following Reconstruction and the Civil War.

- The right to deal with blacks without northern interference.

While the Redeemer portion of the Democratic Party promised the Republican Party that the Southern states would honor the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments protecting the rights of African Americans, these promises were quickly forgotten. By the early 1880s the African American community in the South was returned to a status akin to slavery, with no recourse to the state courts, and being ignored by Federal courts staffed by judges, in particular the Supreme Court, appointed to their positions by the Republican Party up to 1937. From 1937 up to 1945, Franklin Roosevelt appointed 8 Supreme Court justices. It is from this crop of justices that saw the beginnings of enlightened rulings acknowledging the rights of people of color.

The bitter fruits of that compromise is being harvested today on the streets of the United States. It is time that both Republicans and Democrats be called to account for their betrayal of Americans, in particular, those whose only crime was having black skin.