The Case for Castro: Why the Embargo Needs to End in 2015

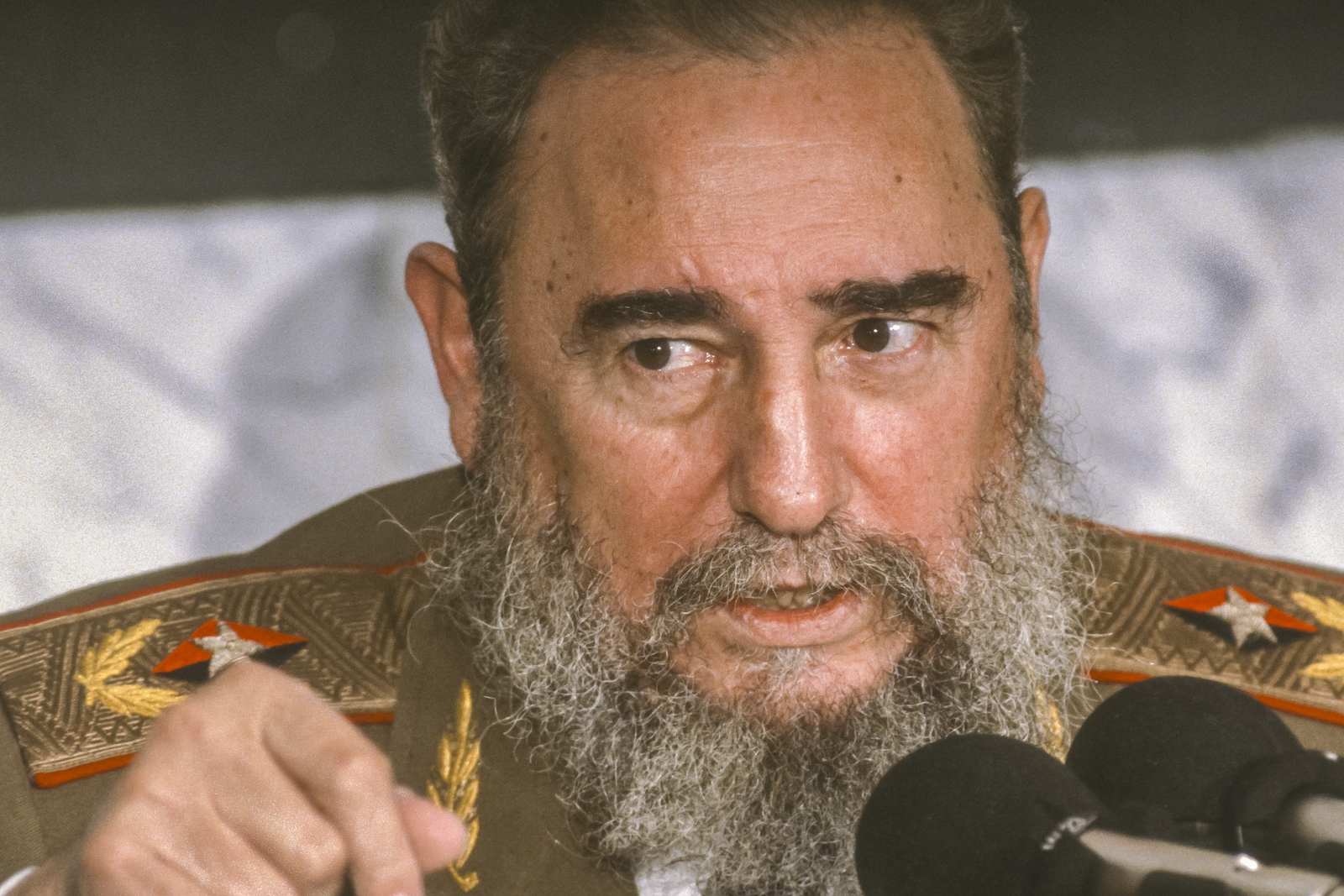

The United States has spent so long trying to supplant Cuba’s communist dictatorship with liberal democracy that surely, after more than five decades, it has exhausted its policy options. It tried to overthrow the Castro regime in 1962. It tried to assassinate Fidel Castro on multiple occasions. Most enduringly, it has severed all diplomatic and economic ties with its neighbor some 90 miles south of Florida. One would think that, after failing so long to achieve its objectives, it is time for the U.S. to change its approach.

After President Obama announced diplomatic rapprochement on December 17, the sizeable and nationally influential Cuban-American contingent in Congress erupted with frenetic, emotionally-charged condemnations declaring the maneuver a “unilateral concession” to the Castro regime. Such rhetoric came not just from frequent Obama critics like Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Ted Cruz (R-TX) but from his own party’s leadership. Outgoing Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Menendez (D-NJ) echoed their sentiment, writing that Obama “has wrongly rewarded a totalitarian regime and thrown [Cuba] an economic lifeline.”

Impassioned as they may be, these and other embargo hawks who vehemently object to lifting the embargo have not proffered any explanation of how prolonging the embargo will improve conditions under the Castro regime. Former Governor Jeb Bush (R-FL) remonstrated that “we should instead be fostering efforts that will truly lead to the fair, legitimate democracy that will ultimately prevail in Cuba,” despite not articulating a single policy alternative that might achieve that end. By reflexively and dogmatically opposing any Castro policy by virtue of its origin, embargo advocates are insisting the unattainable perfect be the enemy of the good.

It is high time to realize that a grand revolutionary moment is never coming to oust the Castro family from power. Democracy will not march down from Sierra Maestra, but will grow over time as the seeds of economic freedom germinate. Whether he knows it or not, President Raúl Castro has ventured Cuba forth on the arduous road to democracy.

Since assuming the presidency in 2006, Raúl has made GDP growth a priority, enacting modest liberal reforms including the relaxation of constraints on private property and industry. These aberrations are representative of a recent trend in Havana: the Communist Party envisions a market economy going forward. At the 2011 Communist Party Congress, it formally adopted a comprehensive plan to transform Cuba’s Soviet-style command economy, loosening central oversight of state-owned enterprises, eliminating universal subsidies, and allowing more small businesses to participate in the means of production. Freedom House notes that these economic reforms have yielded an improvement in civil liberties, with Cuban consumers allowed greater access to goods and the introduction of a state-sponsored campaign against homophobia placing Cuba as a standard-bearer for the LGBT rights movement in Latin America.

While the rest of the world stands to gain from the recent, unanimously-passed law designed to attract massive foreign direct investment, the U.S. self-inflicted policy of isolation shutters its companies from a burgeoning market and, more importantly, continues to prevent itself from leveraging its status as regional hegemon into influence in Havana. Economists project that a full repeal of the embargo could net the United States as much as $4.3 billion annually, primarily in the agricultural sector. Cuba would surely be asymmetrically dependent, importing more from the U.S. than it would export.

In addition, as long as the embargo persists, Castro will continue to exploit it politically, blaming Cuba’s problems on the United States to rally support for the regime and further justify the repression of political opponents and the media. Although purported to punish the Castro regime for their human rights violations, the embargo economically marginalizes ordinary Cubans by helping the regime consolidate control over the economy, keeping the people poor, oppressed, and disenfranchised.

The most potent weapon in the U.S. policy arsenal is economic engagement with positive conditionality. In the past, the U.S. has successfully leveraged bilateral aid to both pursue its regional security interest and project “soft power,” making American values more attractive to aid recipients. After World War II, the Marshall Plan helped rehabilitate European economies and contain the spread of communism.

Today, the U.S. has programs like the Millennium Challenge Corporation, which awards bilateral foreign assistance to states that have made strides to improve three broad categories: “ruling justly,” “investing in people,” and “encouraging economic freedom.” Offering development aid in exchange for political and economic reform ought to be the first step toward bringing Cuba into the IMF, World Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank. However, no efforts to integrate Cuba into the neoliberal economic global order will gain traction in Havana so long as the U.S. Congress insists upon regime change.

President Castro’s acknowledgment that Cuba needs an economic relationship with the largest capitalist country in the world is not a “communist victory,” but the realization that Cuba’s command economy is doomed in absence of a patron. Castro’s economic reforms, as well as his insistence on term limits, suggest that a regime shift (as opposed to a regime change) may be on the horizon in Havana, wherein the domestic political structure is deliberately altered to preserve the ruling position of the family and their cronies. Castro’s triumphant address to parliament in December framed the diplomatic reconciliation as an affirmation of Cuban sovereignty predicated on mutual respect for each country’s political and economic systems, although tacitly acknowledging that some market-oriented reforms are needed to grow the Cuban economy.

As Raúl Castro looks to appoint a successor in 2018, the United States needs to grasp this opportunity to socialize the present regime to the ideals of civil liberty, democracy, and free enterprise. Progress may be painfully slow, but will inch in the right direction. From the U.S. perspective, how can any purported drawbacks to engagement with Communist Cuba worsen either U.S.-Cuba relations or the living conditions of the average Cuban? Cuba’s human rights record is abhorrent, but there is no reason why that should preclude the U.S. from diplomatically and economically engaging with it. Strategic relationships with China and Saudi Arabia exemplify that humanitarian concerns are second-order priorities, and rightfully so.

The embargo was justified during the Cold War when Cuba was a staging ground for Soviet military installments. Today it is an anachronism, an unwarranted policy of economic warfare toward a country that no longer poses a strategic or ideological threat to the United States. Ending the embargo immediately will yield the U.S. favorable economic and diplomatic dividends in its neighborhood and accelerate Cuba’s languid pace of domestic reform.