Books

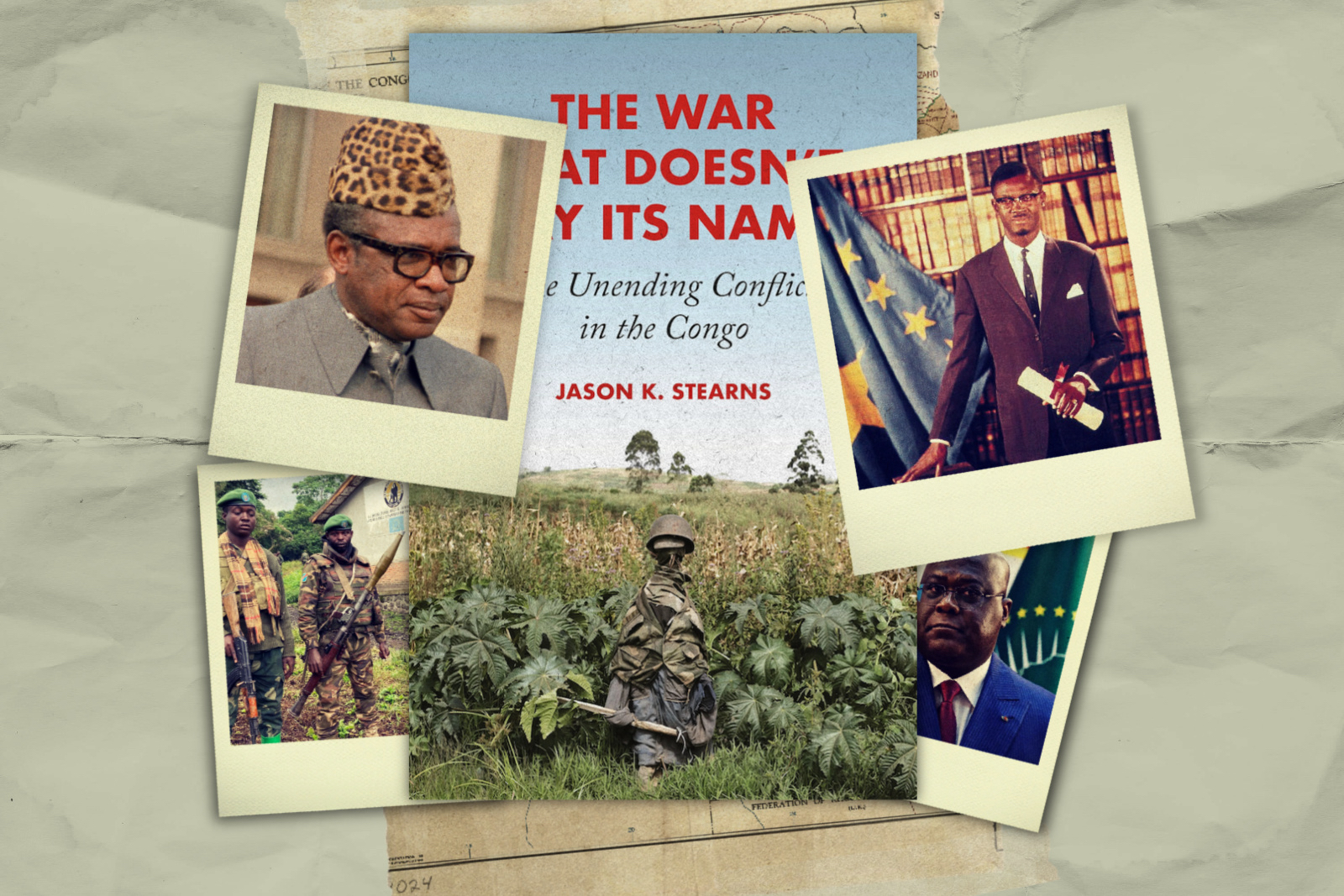

The Fractured Heart of Congo: Self-Sabotage Amidst Bloodshed

Jason K. Stearns’ The War That Doesn’t Say Its Name: The Unending Conflict in the Congo dissects the persistent conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with a sharp, analytical blade. Disregarding the simplistic accounts that point fingers at foreign interventions alone, Stearns turns the examination inward, arguing compellingly that the Congolese government, with its regional allies like Rwanda and Uganda, have been complicit in the country’s chaos—a chaos birthed from a mix of apathy and the strategic extension of warfare.

Stearns suggests a stark reevaluation of culpability. While international donors and multinationals are not beyond reproach, he contends, it is the local players who shoulder a significant burden of responsibility. His critique spares no one, laying bare the despondency of Congolese officials and the corruption that seeps from their ranks to their Rwandan and Ugandan counterparts, albeit less so. The entrenchment of the conflict, he posits, has engendered a new class—the ‘bourgeoisie’ of beneficiaries in both Congo and Rwanda. Stearns calls for a more nuanced engagement from international donors, one that considers the intricate web of rebel factions, their patrons, and the self-serving Congolese army officials shadowed by civilian actors.

The book paints a damning picture of a civil war that has degenerated into a quagmire, escaping the grasp of foreign diplomats, NGOs, and multinationals who are ill-equipped to stem or redirect its course. The peril, Stearns warns, is not merely in the enduring violence but in the potential replication of this cycle in other resource-rich nations, a risk that increases with every failure to appreciate the conflict’s complexity.

This book is heralded for its incisive contribution to understanding the quagmire that is the Congolese nightmare. It pleads for a thoughtful engagement with the nation’s complex history and advocates for the respectful treatment of its people. Yet, it challenges the perception of international actors as naive or clean-handed as portrayed by Stearns. It proposes that the idea of a strong, centralized Congolese state is in direct opposition to the interests of multinationals and the global economic status quo, which thrive on corruption and the relentless quest for profit.

From the book’s early pages, Stearns’ thesis is clear: Congolese elites have no desire for peace, as war serves as their platform for political dialogue. Peace talks, he observes, are nothing but a masquerade, a strategic ploy for more funding and media attention, while behind the scenes, the war machinery grinds on. The book also sheds light on the nature of rebel operations, which are not about overthrowing the government but about making a statement, a bargaining chip in the political game.

Stearns provides historical context, tracing the continuity and evolution of political turmoil from the pre-independence era to the present, underscoring that today’s wars in the Congo, unlike the struggles of yesteryears, are steeped in sectarianism and ethnic rivalry over resources and legitimacy.

Further chapters dissect the altered landscape of conflict post-2003, the role of the Congolese and Rwandan states in perpetuating warfare, and the emergence of a ‘military bourgeoisie’ whose survival depends on the conflict’s continuance without decisive victory or defeat.

In profiling rebel groups such as CNDP (National Congress for the Defence of the People) and M23, or the March 23 Movement, Stearns delineates the micro-dynamics of conflict in Congo from 2003 to 2020. He also explores the Raïa Mutomboki movement and the absence of a military bourgeoisie in Ituri Province, offering a unique perspective on the peace dynamics in different regions.

The book culminates in a critique of international peacemaking efforts, where Stearns underscores the failure of foreign actors to fully engage with the complexities of Congolese governance or to hold regional powers accountable.

Stearns’ methodical approach—from empirical observation to hypothesis formulation and theory construction—lends credibility to his work. The wealth of detail and interviews provides the reader with an intimate view of the conflict, allowing for an independent reassembly of the narrative, different from Stearns’ conclusions. This reassembly reveals a potential pitfall in the narrative that risks reinforcing the stereotype that African conflicts are self-wrought and perpetual.

In his illuminating second chapter, Stearns provides a vital historical context to the current political turmoil in the Congo, comparing and contrasting past conflicts with the enduring ones of today. Past wars, he notes, were deeply rooted in their local societies and histories, much like the ones we witness now. What appears as a shift in political expression from the pre-independence days to the early 2000s is, in essence, a consistent pattern, merely cloaked in new garb. Stearns posits that the ongoing wars bear scant resemblance to the nationalist struggles of yesteryear, embodied by figures such as Patrice Lumumba and Mobutu Sese Seko. He points out a stark deviation: historical conflicts, often brief, centered on development and resource allocation for infrastructure, while contemporary ones are mired in ethnic entitlement and competition for government funds.

Chapter Three outlines how the supposed peace of 2003 merely transformed the conflict, failing to end it. Stearns introduces the concept of transformation theory, noting that the failed integration of rebels into army ranks led to the fragmentation of armed groups. The convoluted electoral process now incentivizes political alliances with militia leaders, equating military strength with political leverage—turning insurrection into a perpetual state.

The fourth chapter is an exploration of the Congolese and Rwandan states’ roles in the conflict’s longevity. Stearns cautions against dismissing his findings as counterintuitive; he asserts that the Congolese government is not invested in peace, and Rwanda’s interference is complex, driven by internal politics and misperceptions. The persistent conflict benefits certain actors, creating a self-sustaining cycle of instability and legitimacy for some regimes.

Chapter Five reveals Stearns’ theory of the violence: a combination of involution, fragmentation, and the emergence of a military bourgeoisie. He describes a status quo defined not by the desire for victory, but for the perpetuation of conflict itself, where the Congolese army paradoxically empowers the enemy, leading to a sprawling array of combatants. This prolonged instability has made the conflict less of a threat to the central government yet more intractable and devastating for civilians.

In Chapter Six, Stearns profiles the rebel groups CNDP and M23, tracing their lineage and underscoring the complexity of the conflict from 2003 to 2020. These groups are emblematic of the disillusionment with Kinshasa, leading to a continuous cycle of fragmentation and rebellion.

Chapter Seven focuses on the grassroots Raïa Mutomboki movement, a decentralized response to rampant insecurity and abuses by other armed groups. Despite its popularity and legitimacy, the movement is not impervious to contradictions and infiltration, highlighting the layered and volatile nature of the conflict.

Chapter Eight contrasts with the preceding chapters by examining the relative peace in Ituri Province. The absence of a military bourgeoisie in Ituri exemplifies how peace can be sustained where commercial and military interests do not converge, and where external interventions prevent the emergence of such interests.

Stearns’ final chapter delivers a pointed critique of the international community’s role in the Congolese quagmire. He singles out foreign entities, especially those in the mining and resource sectors, for their reluctance to delve into the labyrinthine workings of the Congolese government or to demand accountability from regional authorities. This lackluster engagement and the tendency toward overly succinct policy documents squander critical chances to exert substantial influence. Such inaction inadvertently underwrites the ongoing strife, perpetuated by Kinshasa and its neighbors, through a veil of diplomatic and corporate indifference.

The book beckons readers to engage with the conflict’s wider context, to unravel the tapestry of external involvement, and to question the motivations that sustain this enduring state of war. Stearns nudges the reader to peer beneath the superficial narratives and to interrogate the entrenched, systemic dynamics in play. His narrative stands as both a caution and a clarion call—an exhortation to grasp the intricacies of Congo’s tribulations and to reject simplistic accounts that fault the afflicted.

In essence, Stearns’ examination navigates the dichotomy between discerning analysis and the temptation to generalize, presenting the Congo as a nation caught in the crosshairs of domestic turmoil and international machinations—a poignant exemplar of the ramifications that ensue when corporate greed and geopolitical maneuvering go unchecked.