The Horn of Africa, the World’s Most Dangerous Place?

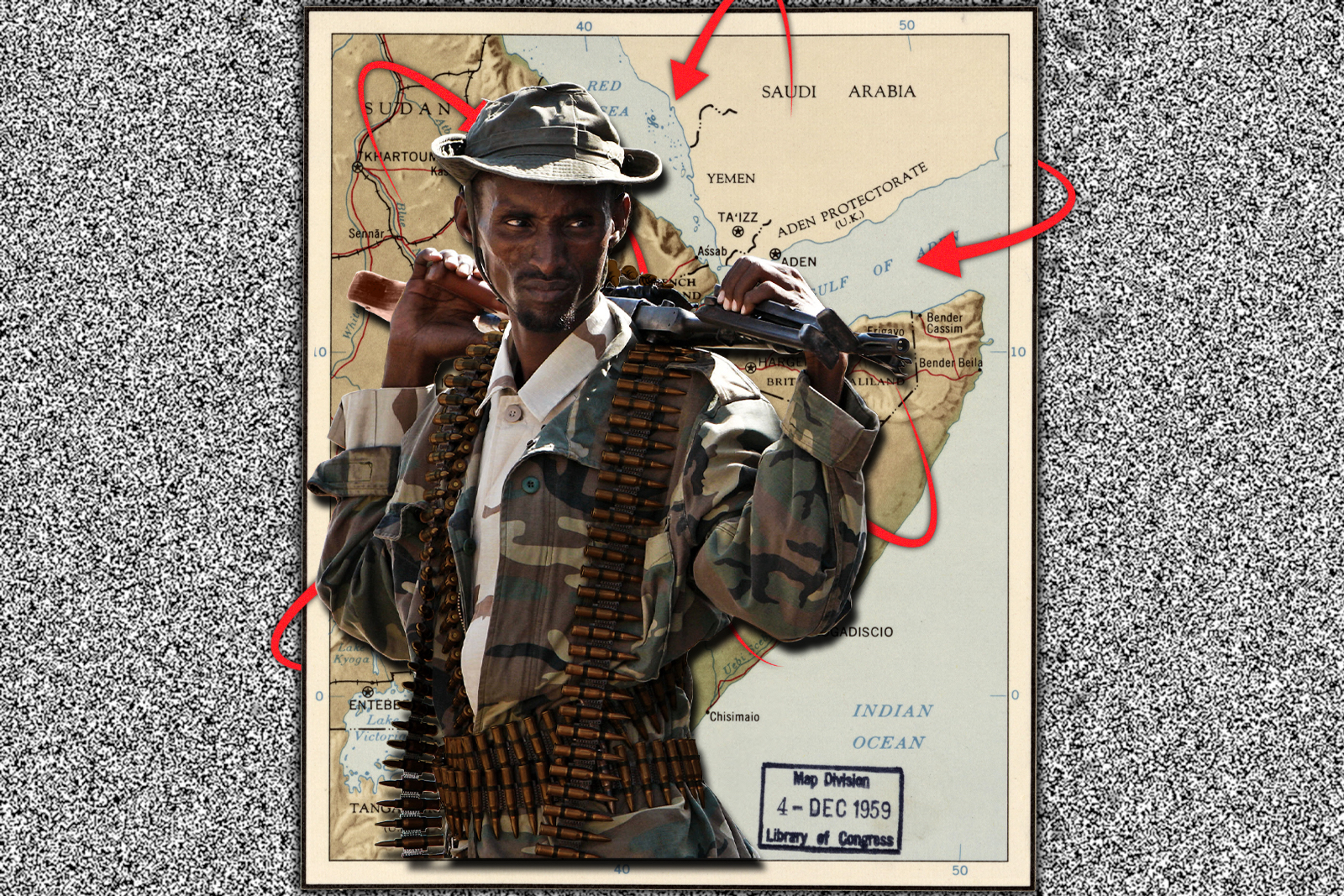

Positioned at the easternmost point of the African continent, the Horn of Africa—also known as the Somali Peninsula—stands as a strategically significant region. Recently, it has become a battleground of foreign interests, rife with ethnic conflicts, civil wars, and coups. These issues are manifold, with deep roots in Colonial history, and they contribute to current challenges, rendering the nations of the Horn highly vulnerable.

During the “Scramble for Africa,” the Horn of Africa was divided among Britain, Italy, and France. The British seized Sudan and a portion of Somalia; Italy occupied a portion of Ethiopia and established Eritrea as a colonial entity, as well as a portion of Somalia; and France occupied Djibouti. As a consequence, the Horn of Africa was divided into five colonial territories (Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Eritrea, and French, Italian, and British Somaliland), while Ethiopia became independent (except for five years of Italian occupation).

Today, six countries make up the Horn—South Sudan and Ethiopia, with nearly 131 million people, are landlocked and desperately need seaport access. Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan, on the other hand, are maritime nations, emphasizing the urgent need for cooperation to fulfill political, social, economic, and security demands.

This geopolitical jigsaw evolved from four original nations: Sudan, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Sudan subsequently split into Sudan and South Sudan, while Ethiopia fragmented into Ethiopia and Eritrea. The turbulent political histories of these countries, marked by conflict dynamics, fragility, and the independence of Eritrea and South Sudan, led to their collective identification as the Horn of Africa.

State fragility in this context encompasses characteristics that significantly hinder economic and social performance, such as weak governance, limited administrative capacity, recurring humanitarian crises, societal tensions, and often, violence or the lingering effects of war.

The Horn’s eight key seaports—Assab, Massawa, Djibouti, Berbera, Bossaso, Mogadishu, Kismayu, and Port Sudan—are vital for the economic success of the region. Remember, Ethiopia was a coastal nation until 1991. Poor political decisions by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, which existed from 1988 to 2019, left the country landlocked, thereby setting the stage for future violent conflicts that could further destabilize the region.

With the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, state fragility and violent conflict in the region became more pronounced. The international community’s waning interest left room for the eventual rise of groups like al-Shabaab to spread terror throughout Somalia, with repercussions extending well beyond the Horn. Ongoing civil wars and internal conflicts underline the region’s fragility. It should be stressed that the implosion of Somalia in the 1990s can be laid at the feet of the former Clinton administration which had all but abandoned the country after the debacle of the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993 and the Bosnian War took center stage.

Simultaneously, renewed global interest in the Horn’s coastal areas has attracted major powers and influential Gulf nations, adding complexities to the region’s instability and emerging security challenges. Countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, China, Japan, the U.S., France, Germany, and Italy have all established military bases near Djibouti and Somalia, fueling geopolitical rivalries.

China and Turkey, specifically, are leveraging their economic clout to shape international politics. China’s focus on maritime commerce has turned Djibouti into a critical pathway for exports to Europe, aligning with its Belt and Road Initiative. Similarly, Turkish investors are drawn to the region, as evidenced by Turkey’s control over the Port in Mogadishu since late 2014.

Furthermore, Turkish investors are being drawn to the Horn because of lucrative contracts. The administration of the Port in Mogadishu was taken over by the Turkish company Albayrak Group in late 2014. At the end of 2017, Turkey revealed that it had been granted a lease to run and reconstruct Suakin, a historic Ottoman port city in northeastern Sudan. According to reports, the deal covers naval infrastructure and military cooperation between Turkey and Sudan. The region’s significance in the broader intra-Middle Eastern rivalry that culminated in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) conflict—pitting Qatar and Turkey against the Saudi-led coalition—is undeniable.

The instability and ongoing conflicts in the Horn of Africa have created negative security externalities, including internal migration, refugee flows, organized crime, terrorism, illegal trade, and the spread of small arms. As per the 2023 Global Peace Index, the Horn remains one of the most adversely affected regions, compounded by drought and famine affecting over 23 million people in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. Mortality and malnutrition rates continue to be major sources of concern.

Moreover, the Horn of Africa is among the world’s most conflict-ridden areas. The long-term effects of COVID, climate change, ongoing warfare, global financial uncertainty, and the war in Ukraine have all contributed to food insecurity. An unprecedented hunger crisis looms, with 60 million people facing extreme starvation and water scarcity.

Persistent drought and high food costs have hindered the ability to grow crops and purchase food, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. Conflict and violence have only worsened the natural disasters’ impact, creating new challenges for international aid organizations. Though efforts to mitigate drought effects have seen some success, they fall short of meeting the massive need. Both immediate humanitarian response and long-term climate initiatives are vital due to the interwoven climatic and political crises.

In terms of length and intensity, Somalia’s most recent drought outlasted droughts in 2010 and 2016. In Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, more than 23.5 million people were suffering from extreme food insecurity as of May. According to the World Food Programme, organized violence and armed conflict remain important drivers of severe food insecurity in a number of hunger hotspots throughout the world, including Ethiopia and Somalia. Conflict continues to undermine the livelihoods of Somalis, notably in the central and southern regions.

The situation has been made far worse by Russia’s decision to pull out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative. During a meeting with African heads-of-state at the Kremlin recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin offered adversely affected countries free grain, but it won’t be enough to solve the food crisis facing the people of the region.

Despite receiving billions in humanitarian assistance for over three decades, Somalia remains one of the most dangerous places for aid workers. The threat of counter-terrorism sanctions hampers relief distribution. Since Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud initiated a campaign against al-Shabaab in August 2022, attacks have surged. The country’s insecurity is further highlighted by escalating car bombs and other violent incidents.

The mental health toll on Somalis, suffering from traumatic events like war, famine, and displacement, is enormous. According to preliminary research, 76% of Somalis have faced such challenges, resulting in “invisible wounds” that hinder healing, reconciliation, and civic engagement.

Climate change, wars, and food security are interlinked in fragile contexts. Both state and non-state actors in the region frequently obstruct access to affected populations. Some scholars advocate for focusing on the root causes of conflict and promoting international collaboration for “African solutions to African problems.”

The ripple effects of violent conflict erode state authority, efficiency, and legitimacy in the Horn. Understanding the intricate relationship between state fragility and conflict dynamics is key to grasping the current security predicament facing the Horn of Africa.

Fragile governments inherently require robust institutional capacity to satisfy socioeconomic needs, political legitimacy for representation, and the functional authority to maintain security within their borders. Early warning, timely intervention, and social safety programs are essential in addressing food insecurity and famine. However, they may not be enough. The entire response must be cognizant of the historical violence and its ongoing effects across the Horn of Africa.