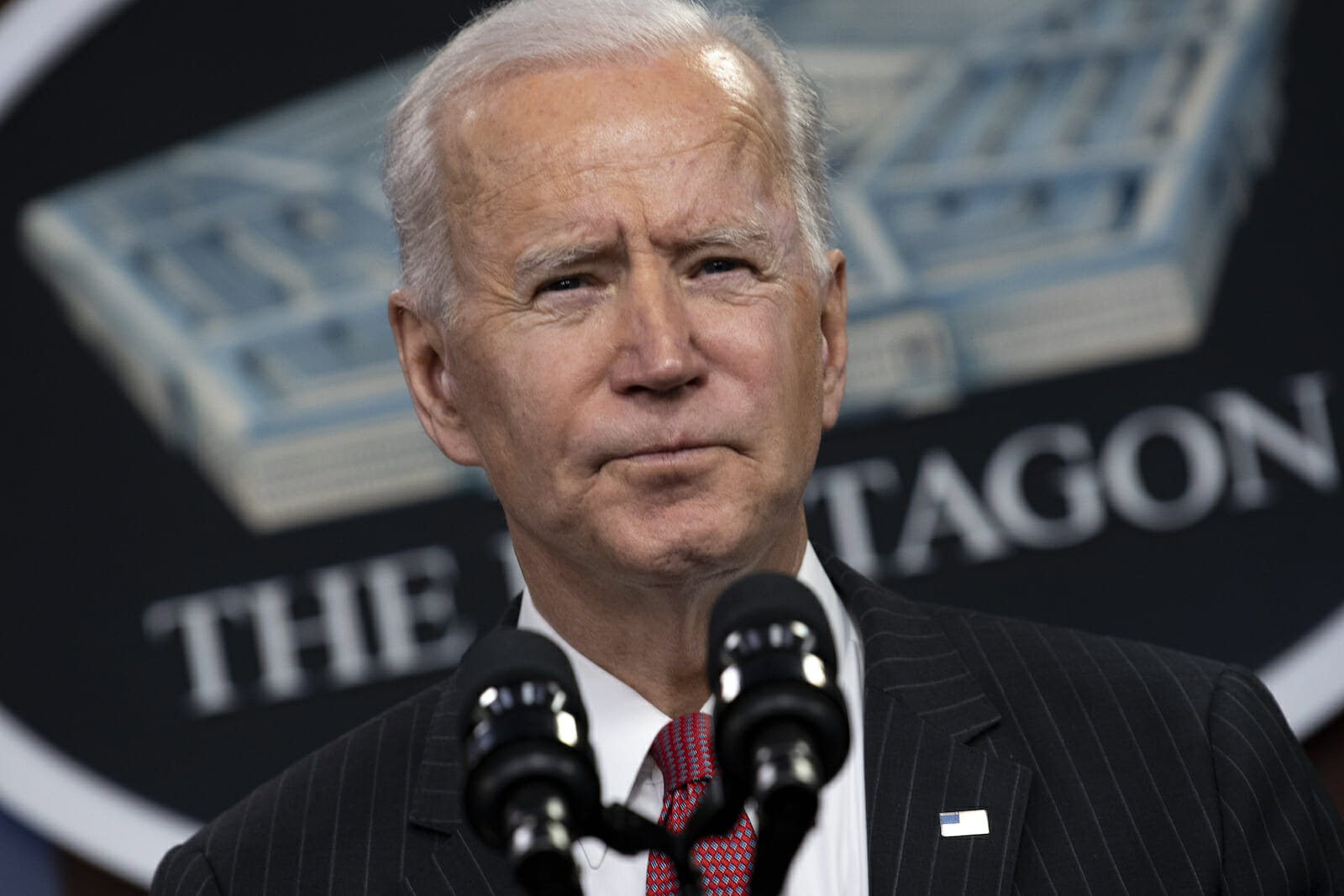

The ‘Return’ of America: Biden’s Maiden Foreign Policy Speech

Few could have been slack-jawed at the first significant foreign policy speech of US President Joe Biden. It can easily be filed under the “America is back” label. Back as well, as if the previous administration had been incapable of it, was a promise for that practice unflatteringly called jaw-jaw. “Diplomacy,” the president states from the outset, “is back at the centre of our foreign policy.”

Doing so naturally meant much cap doffing to the US State Department, that long time enunciator of Washington’s imperial policies. President Donald Trump had held a rather different view of the department he generally saw as fustian and obstructive. Biden tried reassuring department staff that he valued their expertise, respected them, and would have their back. “This administration is going to empower you to do your jobs, not target or politicize you.”

The effort of the new administration, outlined by Biden, will focus on repairing and restoring. Paint and scaffolding will be provided. Alliances will be revisited, the world engaged with. He strikes a collaborative note: cooperation with other states will be needed to fight the pandemic, climate change, and nuclear proliferation.

The speech has the usual sprinklings of concern and fear that other powers are posing challenges to US power, but is odd in not mentioning such states as Iran, at least explicitly, or North Korea. “American leadership,” he urges, “must meet this new moment of advancing authoritarianism, including the growing ambitions of China to rival the United States and the determination of Russia to damage and disrupt our democracy.” Beijing remained “our most serious competitor” and needed to be pushed back “on human rights, intellectual property, and global governance.” He asserts that the US will not roll over “in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions” and will be more “effective in dealing” with Moscow “in coalition and coordination with other like-minded partners.”

This leaves the impression that the Trump administration was in the business of playing amiable golf with the Putin regime, a point that Democrats in Congress were always keen to push. But whatever Trump’s strong man admiration might have been for President Vladimir Putin, the US record during his time in office was far from accommodating. An overview of the various retaliatory sanctions is provided by the Brookings Institute. They are many and include, among others, the imposition of sanctions in response to Russia’s alleged use of a nerve agent in the British town of Salisbury in 2018; the sanctioning of Russian and a Chechen group for human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings and torture; and sanctions for alleged Russian electoral interference in 2018.

The speech also pays a mandatory pound of cant masquerading as homage to the misunderstood idea of democracy. He spoke of defending “America’s most cherished democratic values: defending freedom, championing opportunity, upholding universal human rights, respecting the rule of law, and treating every person with dignity.”

Democracy is always a conceptual problem for presidents, largely because the US executive and the country’s political system is a creation of a distinctly non-democratic mindset. The framers of the US Constitution pooh-poohed democracy and purposely crafted a document and political system that would protect property, stifle the emancipation of slaves, and neutralise factionalism.

Historians such as Charles Beard developed these ideas in An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution (1913), noting how that celebrated document was ratified by fewer than one-sixth of adult males and excluding the un-propertied franchise. “The Constitution was not created by the ‘whole people,’ as the jurists said…but was the work of a consolidated group whose interests knew no state boundaries and were truly national in scope.” Drafters of the Constitution “with a few exceptions, immediately, directly and personally interested in, and derived economic advantages from, the establishment of a new system.” Things were off to a cracking start.

A recent smattering of critique of that problematic notion that is American democracy can also be found, if one cares to look. Political scientist Yascha Mounk, looking at the foiled efforts of residents in Oxford, Massachusetts to secure the local water supply by buying out the company in question, Aquarion, furnishes us a gloomy example. Despite securing enough funding to achieve their goal, the lobbyists and a generous effort at sabotage ensured that the water company would remain the supplier. “The preferences of the average American appear,” rues Mounk, “to have only a miniscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.”

The Trump era, while channeling the concerns of the powerless, left it at that. Elites were still in rampant play, if only those elites preferred by the president. The US republic moved ever more deeply into a terrain crawling with billionaires and lobbyists. It was left for those against Trump and the Democrats to simply identify how best to retake old, unequitable terrain with their substitutes. The participating voter could well sod off.

Problematically, we return to democracy as an exportable commodity, an effort that has been, for the most part, a disastrous platform of US foreign policy. Previous sages warned that democracy grown in indigenous climes, like certain wines, travel poorly. Not acknowledging this fact has led to quagmires, the destruction of states, and the crippling of regional and in some cases global security.

Despite the US being sketchy about democratic ideals (he does allude to the Capitol riots), Biden is optimistic that “the American people are going to emerge from this moment stronger, more determined, and better equipped to unite the world in fighting to defend democracy, because we have fought for it ourselves.” He also announced “additional steps to course-correct our foreign policy and better unite democratic values with our diplomatic leadership.” A Global Posture Review of US forces would be conducted, which could only mean one thing: butting the brake on withdrawing US troops and reversing Trump’s policy in various theatres.

He suggests an example of democracy promotion in action: marshaling cooperative support to address the military coup in Burma; reaching out to the Republicans to test the waters (Senator Mitch McConnell also “shared concerns about the situation in Burma”). Force, he proclaimed “should never seek to overrule the will of the people or attempt to erase the outcome of a credible election.” The ghosts of Chile’s Salvador Allende and Iran’s Mohammad Mosaddegh, along with many other casualties of US efforts to overrule the will of the people, would beg to differ.

A more positive note is made on the issue of US support for the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen, where an effort will be made to support UN-led initiatives “to impose a ceasefire, open humanitarian channels, and restore long-dormant peace talks.” US support for offensive operations in the war, including arms sales, will also cease.

What we can expect for a good deal of the Biden administration will be the resuscitation of the hackneyed and weary. Even such an ordinary speech had Fred Kaplan claiming that Biden’s cliché’s, after Trump, sounded “revolutionary.” Trump’s four years had been characterised by “diplomatic decline and atrophy”; Biden’s views, in light of that, “seemed fresh, even bracing.” But Kaplan is not immune to the substance here. Talk about stiffening democracy’s sinews, shoring up alliances when allies are doing their own deals with opponents, can come across as rather weak. The pudding, and the proof that will come with it, is still being made.