Turkey Wants to Reconcile with Assad

At first glance, there is little that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has in common with Doğu Perinçek, a maverick socialist, Eurasianist, and militant secularist and Kemalist.

Yet it is Perinçek, a man with a world of contacts in Russia, China, Iran, and Syria whose conspiratorial worldview identifies the United States as the core of all evil, that Erdoğan at times turns to help resolve delicate geopolitical issues.

Seven years ago, Perinçek mediated a reconciliation between Moscow and Ankara following Turkey’s downing of a Russian fighter jet.

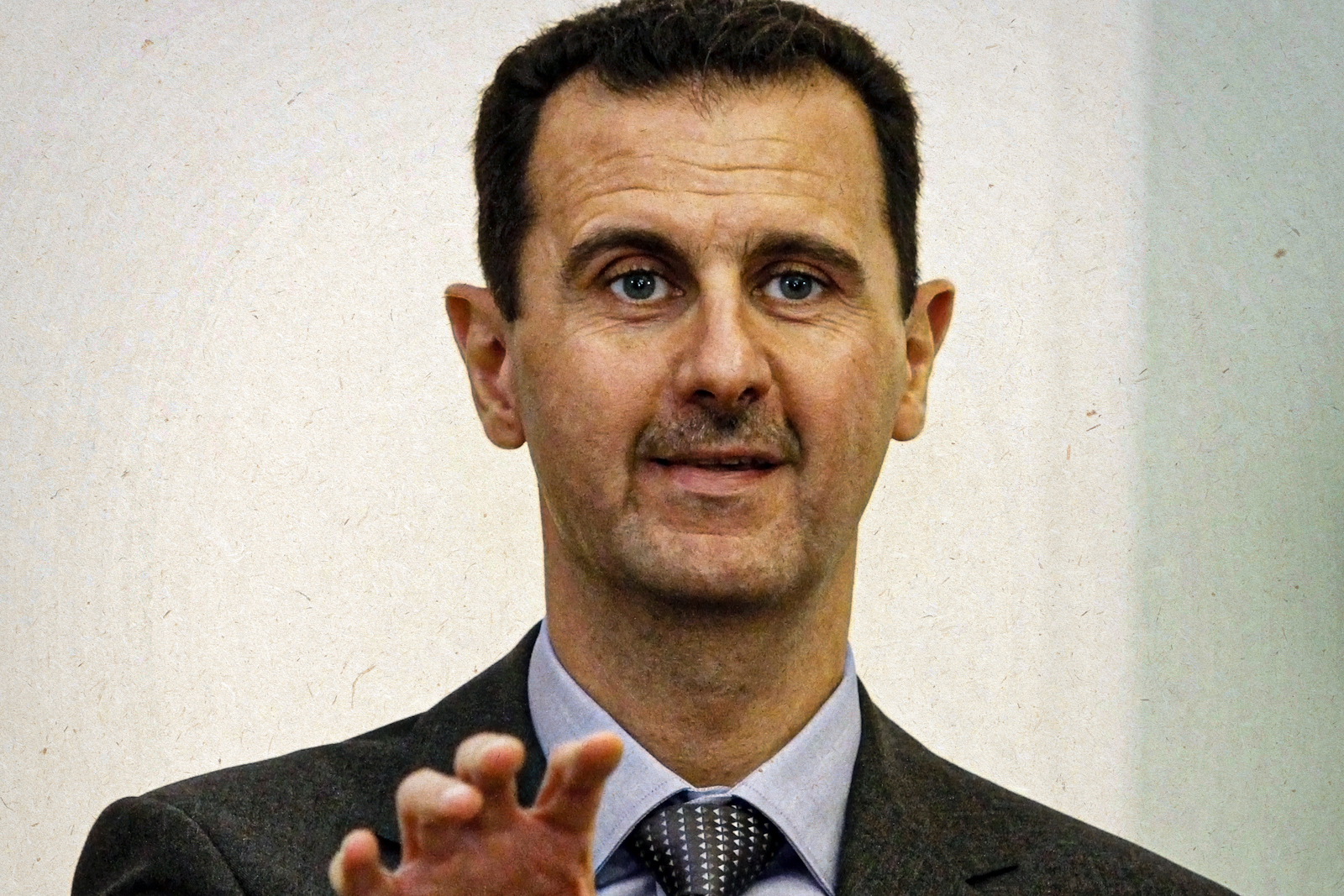

Now, Perinçek is headed to Damascus to engineer a Russian-backed rapprochement with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose overthrow Erdoğan had encouraged for the past 11 years ever since the eruption of mass Arab Spring-era anti-government demonstrations that morphed into a bloody civil war.

Chances are that Perinçek’s effort will be more successful than when he last tried in 2016 to patch up differences between Erdoğan and Assad but ultimately stumbled over the Turkish leader’s refusal to drop his insistence that the Syrian president must go.

Erdoğan has suggested as much in recent days, insisting that Turkey needed to maintain a dialogue with the government of Assad. “We don’t have such an issue whether to defeat Assad or not…You have to accept that you cannot cut the political dialogue and diplomacy between the states. There should always be such dialogues.”

Erdoğan went on to say that “we do not eye Syrian territory…The integrity of their territory is important to us. The regime must be aware of this.”

Erdoğan’s willingness to bury the war hatchet follows his failure to garner Russian and Iranian acquiescence for a renewed Turkish military operation in northern Syria. The operation was intended to ensure that U.S.-backed Syrian Kurds, whom Turkey views as terrorists, do not create a self-ruling Kurdish region on Turkey’s border like the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Iraq.

Turkey hoped the operation would allow it to create a buffer zone controlled by its forces and its Syrian proxies on the Syrian side of the two countries border.

Russia and Iran’s refusal to back the scheme, which would have undermined the authority of Assad, has forced Turkey to limit its operation to shelling Kurdish and Syrian military positions.

The United States seeming unwillingness to offer the Kurds anything more than verbal support, and only that sparsely, has driven the Kurds closer to Damascus and, by extension, Russia and Iran as Syria quietly expands its military presence in the region. The U.S. has long relied on the Kurds to counter the Islamic State in northern Syria.

The rejiggering of relationships and alliances in Syria is occurring on both the diplomatic and military battlefield.

The Turkish attacks and responses by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) at its core appear to be as much a military as a political drawing of battlelines in anticipation of changing Turkish and Kurdish relations with the Assad government.

By targeting Syrian military forces, Turkey is signaling that it will not stand idly by if Syria supports the Kurds or provides them cover, while unprecedented Kurdish targeting of Turkish forces suggests that the Kurds have adopted new rules of engagement. Turkey is further messaging that it retains the right to target Kurdish forces at will, much like it does in northern Iraq.

Both Erdoğan and the Kurds are placing risky bets.

The Kurds hope against all odds that Assad will repay the favour of allowing the president to advance his goal of gaining control of parts of Syria held by rebel forces and forcing a withdrawal of U.S. forces from the area by granting the Kurds a measure of autonomy.

With elections in Turkey looming, Erdoğan hopes that Assad will help him cater to nationalist anti-Kurdish and anti-migrant sentiment by taking control of Kurdish areas.

Turkey wants to start repatriating some of the four million predominantly Syrian refugees it hosts. In early August, Turkey announced that it had completed the construction of more than 60,000 homes for returning refugees to northeastern Syria.

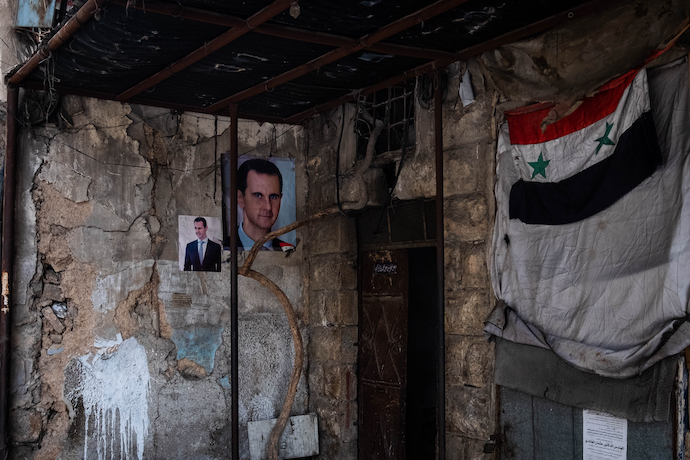

Concern about a potential deal with Assad and a call by Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu for reconciliation between opposition groups and Damascus sparked anti-Turkish protests in Turkish-controlled areas of northern Syria as well as rebel-held Idlib.

Turkey also expects Assad, who is keen to regain not only territorial control but also maintain centralized power, to ultimately crack down on armed Kurdish groups and efforts to sustain autonomously governed Kurdish areas.

As a result, Perinçek, alongside Turkish-Syrian intelligence contacts, has his work cut out for him. The gap between Turkish and Syrian aspirations is wide.

Assad wants a complete withdrawal of Turkish forces and the return of Syrian control of Kurdish and rebel-held areas. He is unlikely willing or able to provide the kind of security guarantees that Turkey would demand.

Both the Kurds and Erdoğan are caught in Catch-22s of their own that does not bode well for either.

The Kurds may be left with no options if a Turkish-Syrian rapprochement succeeds or face a Turkish onslaught if it fails.

Similarly, reconciliation on terms acceptable to Erdoğan may amount to pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

Whether he agrees with Assad or violence in northern Syria escalates, Erdoğan risks sparking a new wave of refugees making its way to Turkey at a time that he can economically and politically least afford it.

According to analyst Kamal Alam, Erdoğan’s problem is that the Turkish president “is running out of time before the next election to solve the Gordian knot that is Syria. For his part, Assad can wait this out – because after Turkey once again fails to bomb its way out of the northeastern problem, Erdoğan will need Assad far more than the reverse.”