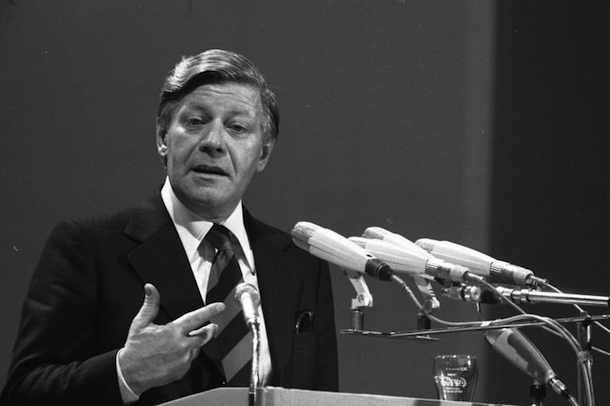

Two Track Grouch: Helmut Schmidt’s Legacy

The 96-year-old Helmut Schmidt was one of those creatures of diplomacy some choose to call pragmatic. He was certainly no fire brand, keen, in truth, to douse the flames of revolution with market managerial dullness and steady containment. While he did stem from the Social Democrats, it would be a mistake to assume that this tilted him much to the Left. In the pantheon of German chancellors, he tends to be shaded, undeservedly, by Konrad Adenauer, architect of Westpolitik, Willy Brandt, designer of Ostpolitik, and Helmut Kohl, the chancellor of reunification.

Schmidt detested the vision game, the revolutionary motif, the demagogue’s hook to catch the populace. “Anyone with a vision should go to the doctor.” Political change, notably of the democratic nature, could only take place in carefully chartered increments.

None of this was surprising, given the calamitous history Schmidt and his contemporaries had witnessed, and participated in. Growing up in Nazi Germany had various forming, and in some cases deforming effects. When asked about his role in the Luftwaffe, he was dismissive. “You’ll never understand.” That did not prevent him was expressing opinions about the gaining of wisdom. “Die heutigen wissen alles besser” – that “people today know everything better” – was a stark statement of painful growth through awareness.

What typified Schmidt’s approach as German chancellor between 1974 and 1982 were policies that one either regards as part of his pragmatic world view, or of a more cynical play on geopolitical survival.

He kept Moscow and East Germany in the loop even as he pushed for greater relevance and involvement of NATO and Europe. This was the straddling of two chairs without necessarily falling between them – no mean feat.

Cooperation was always better than snubbing, a point he made clear to Chancellor Angela Merkel last year when he urged taking a milder line towards Putin. Without Russia, the somnambulists of history would again take the world to war.

There were, however, exceptions. In the “German Autumn” of 1977, Schmidt had no enthusiasm negotiating with niggling, occasionally violent local adversaries. Communist angst and critique about the lingering presence of ex-Nazis in the West German political and industrial structure led to a spate of actions on the part of the Red Army Faction. Hanns Martin Schleyer, former SS Obersturmführer and industrialist, was kidnapped in an act of symbolic violence. Palestinians in solidarity with the RAF hijacked a Lufthansa plane which finally landed in Mogadishu airport.

The hijackers’ demands of $15 million coupled with the release of 10 imprisoned RAF members were coolly dismissed. The Palestinians were subsequently killed in a German special forces operation, and Schleyer murdered.

He also had his issues with those Imperial dynasts across the pond whose security guarantees he needed. Schmidt did himself have a particularly authoritarian manner, and had assumed considerable standing among Western powers. There was even a suggestion that he would be its de facto leader rather than any White House occupant. That was certainly the case under a mentally feeble Gerald Ford.

The succeeding Carter administration proved problematic for Schmidt, who regarded the Georgian in the White House as defective, be it in knowledge of security policy or economics. He responded to Washington with his famed tongue, lashing officials, and driving Carter to the point of exasperation. Carter thought Schmidt’s behaviour at times resembled that “of a paranoid child,” obsessed about lecturing “on economic matters and […] the history of Germany’s great sacrifice to help other nations overcome their economic problems.”

In 1978, Carter would scribble in his diary that, “Schmidt seems to go up and down in his psychological attitude. I guess women are not the only ones to have periods.” Even the CIA got onto the case of noting his various critical remarks, and supplied a psychologist to decode the inner Schmidt. Could it have been a thyroid condition, surmised Carter?

Schmidt may well have had a point on the White House. While the euro-zone crisis has done no favours to his legacy, he was a pioneering figure in the European monetary system which was conceived in response to the global economic crisis of the 1970s. Carter proved slow in catching up.

It would be folly to suggest that within Schmidt’s psyche lay the slumbering pacifist waiting to get out. His war experiences taught him horror, but they also taught him to prepare for the next one, an instinctive, militarist preoccupation. It assumed the form of his fateful stab at Cold War fame in 1979.

The Guadeloupe meeting of the West’s Big Four, Britain, France, Germany and the United States, saw all those frivolities one has come to expect from leaders at such summits. Even prior to the APEC dress code and themed parties, these individuals could be seen talking about weapons of death and snorkelling in turns. But beyond that, it cemented West Germany’s role in permitting NATO to deploy hundreds of nuclear missiles on German soil. The dual-track decision of December 1979 was born in the Caribbean.

Working on Schmidt’s role in this affair, scholar Kristina Spohr showed a more forceful and engaged leader keen to engage in a Jekyll-Hyde manoeuvre of modernising nuclear forces in Europe on the one hand while pursuing arms limitation talks with the Soviet Union on the other. “Schmidt ultimately emerged as the de facto designer of the alliance’s dual-track decision, in spite of his country’s precarious geopolitical position and non-nuclear status.”

Schmidt had a large, looming eye on the Soviets who had busied themselves with altering, actual or otherwise, the nuclear balance (if there can ever be such a thing) in Europe with the deployment of intermediate SS-20 missiles. Such weapons did not figure in the arms limitation status quo, and Western leaders were wondering whether to push the issue with Moscow.

In any case, a conflict between NATO and Warsaw Pact forces was going to lay waste to Germany – both West and East. Nuclear missiles became dark and dangerous bargaining chips on the European chess board, a point noted by the 300,000 protestors who took to the streets of Bonn in October 1981.

Such positions riled younger progressives in the Social Democrats who took issue with the chancellor’s scorn for environmentalists and his cosy endorsement of nuclear power. Such divisions cost him dearly. In another fundamental sense, Schmidt helped shape, no doubt unintentionally, another part of Germany, one environmentally attuned and stubbornly progressive.