Culture

Untermenschen & the Psychology of Cruelty

To a well-adjusted mind, all human beings are equal. We are created equally in the image of God to spread the messages of peace and justice throughout the world. Of course, this is a subjective spiritual explanation for humanity’s purpose. History has shown that human beings routinely — and abhorrently — fail this ideal. And while it may be problematic for the average person to engage in an act of cruelty toward another human being under normal circumstances, history tells us that extreme political, racial, and societal manipulators often engage in a process of systemic dehumanization to further systemic oppression and instill an instinct toward brutality. Once a group of human beings is no longer viewed as human but as dangerous parasites or vermin unworthy of sharing oxygen, then they are a threat that must be vanquished at all costs.

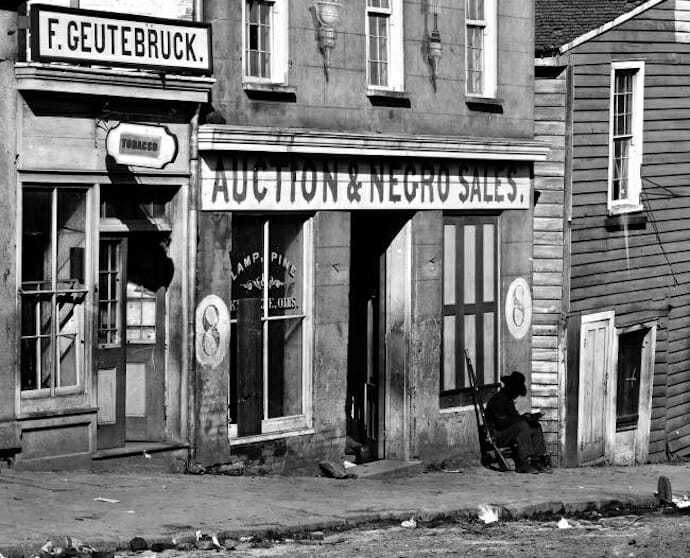

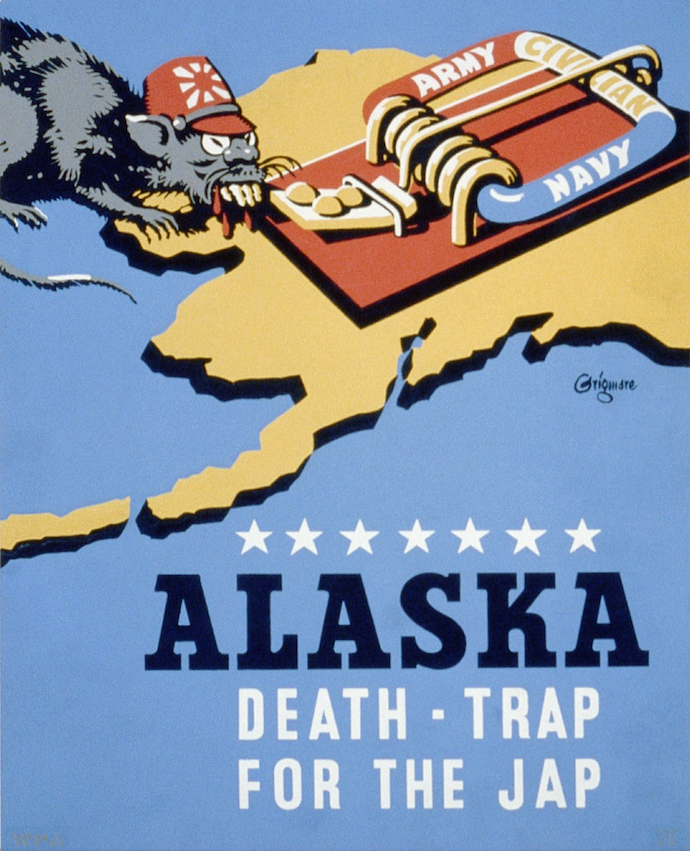

Once “the other” is made non-human, cruelty becomes that much easier. Lamentably, the lineage of cruelty extends to the earliest moments of civilization. Slaves were called animals or worse by their owners, political demagogues, even people of faith. In the years leading to the ultimate destruction of the Holocaust, Jews were commonly referred to as rats. Likewise, in the lead up to the horror of the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s, the majority Hutus referred to the minority Tutsi population as cockroaches. In both cases, the implication is clear: The only way to get rid of pests is to exterminate them.

Hateful words hurt. Dehumanizing terms hurt. In his book Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others, David Livingstone Smith, professor of philosophy at the University of New England, writes: “When people dehumanize others, they actually conceive of them as subhuman creatures.” Only then can the process begin to”liberate aggression and exclude the target of aggression from the moral community.” When the Nazis labeled the Jews as Untermenschen, literally under people, they didn’t just mean this metaphorically. Smith writes: “They didn’t mean they were like subhumans. They meant they were literally subhuman.”

Systemic Dehumanization has an unfortunate legacy in America. The xenophobic Know-Nothing Party, with its slogan “Americans Shall Rule America,” championed repressive measures toward immigrants. In 1856, as the American Party, these xenophobes nominated former President Millard Fillmore for President, and he won more than 20 percent of the popular vote. (We need not recapitulate the brutality of American slavery here, for are all still grappling with its destructive heritage on this nation’s conscience.) When more than one million Irish immigrants came to America to flee the famines of the mid-1800s, many Americans felt threatened by the large number of (mostly Catholic) newcomers. In response, throughout this time period, political cartoonists depicted Irish immigrants as apelike creatures who were inherently drunk, lazy, supportive of corrupt politicians, and prone to bomb-throwing. Many people would be surprised to learn that many of the most virulently bigoted illustrations were penned by Thomas Nast, one of the most influential and respected commercial artists in American history.

In our contemporary moment, dehumanization has flourished. During the early days of the Presidency of Barack Obama in 2009, the New York Post, which is owned and operated by Rupert Murdoch, published a cartoon in which it was clearly indicated that a dead chimpanzee represented the President. More recently, of course, rhetoric no less toxic has been spouted by incumbent President Donald J. Trump and his acolytes. In May of this year, for example, during roundtable discussion on sanctuary cities that resist efforts to aggressively deport undocumented aliens, one discussant mentioned the violent gang MS-13.

In response to the statement, the president said: “We have people coming into the country, or trying to come in — and we’re stopping a lot of them…You wouldn’t believe how bad these people are. These aren’t people. These are animals.”

While President Trump and his supporters maintained that he was only addressing MS-13, the prevailing imagery was evident to his base as well as to thinking people. Megan McArdle, writing in the Chicago Tribune, noted that the “animals” comment, repeated often in the days following the meeting, had an underlying significance: “[The President used] those words to demote those people from the human race…to demote immigrants from the empathy and consideration that decent people extend to other human beings.” At the same time, the president was careful to not denounce the congregation of white nationalist terror in Charlottesville, nor has he denounced the Russian mafia in spite of its vicious activities.

The plain meaning of the “animals” comment is easily gleaned from earlier statements. In June 2015, while launching his Presidential campaign, Trump said: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” Thus, the meaning has always been to demonize immigrants who cross the border from Mexico. This may also explain why the Trump Administration changed government policy so that everyone entering the United States from Mexico is scheduled for criminal prosecution instead of being sent to civil court, thus separating parents from their children. In late 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services contacted 7,635 immigrant children who had been placed with sponsors, and found that 1,475 (nearly one-fifth) could not be accounted for. This is only a fraction of the children taken at the border.

Only by dehumanizing people can these abuses be tolerated. When selected populations (such as racial groups) are deprived of their normal human qualities, the consequences can be horrific.

Hateful words hurt. Dehumanizing terms hurt. The president’s words hurt. Researchers from the University of Warwick, United Kingdom, recently found a correlation between President Trump’s Twitter messages of hate against Latinos and Muslims and FBI crime data showing a subsequent uptick of hate crimes.

Will decency ever be restored to its rightful place in society? It’s hard to say for sure. Often times, we are fed propaganda to view enemies as “soulless” or less than worthy to have the appellation of “human.” As always, these lies are folly. The untruths are the product of myopia and political expediency. Yet, these forced definitions enable others, perhaps even ourselves, to commit atrocities that are despicable, such as torture, incarceration without trial, or indiscriminate bombing. The way we deploy language is tied deeply with our outlook on the world. It is the obligation of all fair-minded citizens, now more than ever, to fight back against the cynical vituperation of certain elements in our midst to restore a semblance of decency back into the world.