Usual Suspects Shaping Migration Patterns in the Middle East

Water scarcity, worsened by climate change, has contributed to a rise in global migration, and nowhere is this more evident than in the Middle East and North Africa. Climate change, environmental degradation, and water stress drive extreme migration patterns throughout the region. As climate change intensifies in states with weakened central governments, armed groups, and extremist organizations have exploited these challenges and weaponized water.

These water-stressed countries, which already face high levels of poverty, are extremely vulnerable to negative climate and water-related impacts on agriculture and health. If the world continues on this path of environmental destruction, the tactical weaponization and denial of water to civilians will continue to place strains on political systems, causing mass migration and internal displacement across the region.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned us as early as 1990 that migration was going to be one of the most considerable global challenges caused by climate change. The World Bank reports that the region is a “global hotspot of unsustainable water use.” The United Nations World Water Assessment Program estimates 1.8 billion people will inhabit regions with absolute water scarcity by 2025. Extreme weather conditions and the severe imbalance of power in the Middle East exacerbate the region’s existing water scarcity, as do poor governance and water management. Extremist groups then take advantage of nations’ fragility, resulting in widespread interstate conflict and further mass displacement.

Water stress across the region allows armed groups to manipulate water as a weapon. Since 2011, there have been more than 180 instances of water infrastructure—which can include drinking water, irrigation, sanitation, and purification of water—being targeted in Middle Eastern nations. As water and food supplies become limited, tensions over access to these resources can trigger violent conflicts in already fragile states. Furthermore, a World Bank report suggests that at least 60 percent of water resources in the region are transboundary, necessitating international cooperation and management.

Since these underground aquifers cross international borders and are not defined by the political landscape, effective management of its resources demands cooperation between all parties involved. Israel and Palestine, for example, are forced by their geographic and political situations to share water resources, which can become a source of disagreement. Under the Oslo II Accord, Israel controls approximately 80 percent of all transboundary water reserves, leaving Palestine with limited resources. As in other conflict zones in the Middle East, competition over secure water supplies can fuel violent conflicts.

Recognizing the connection between environmental weaknesses and the advancement of armed groups is critical to understanding the water-war strategy and its contribution to increased migration. The manipulation of the Tigris and Euphrates river systems as an instrument of violence is a reoccurring feature in Iraq’s history. Extremist groups often take direct, deliberate actions, such as forcefully flooding an area to displace communities, which can have damaging economic consequences. The Islamic State is one such extremist group that uses hydro-terrorism to strengthen its ideology and increase the size of its force. For example, IS saw a 60-70 percent increase in Syrian fighters locally after it manipulated the Islamic Administration for Public Services and polluted local water shelters. The rise of militant extremism allowed IS to exploit the vulnerability of local communities with the promise of its private resources.

The Islamic State has integrated the weaponization of water into its ideology, leading to long-term and permanent migration. The use of water in violent conflicts is not new, but it became more prevalent during the Syrian and Iraqi civil wars. For example, in response to the Marsh Arabs’ 1991 post-Gulf War rebellion against the Iraqi government, Saddam Hussein diverted water flow to the southern marshes, displacing over 100,000 families. States and armed groups can meet political goals and gain control over territories by manipulating the region’s water infrastructure and contaminating reserves.

The Islamic State, for example, has strategically weaponized water in several instances. In 2014, IS militants took control of a dam in Fallujah and deliberately held back water reserves, and orchestrated severe floods, forcing families to seek refuge. IS, by reducing water flow and contaminating the existing water supply, forced people in southern Iraq to flee after their scant water supply became undrinkable. IS also employed this strategy with the Tigris River; they diverted the river water to flood areas of Mansouriya in Iraq, destroying agricultural lands and homes and suspending clean drinking water.

IS continues to be a powerful insurgent force in the Middle East, particularly in Iraq and Syria, contributing to forced displacement and migration. Though political violence and armed conflict drive families to seek refuge, climate change and water scarcity contribute more significantly to rural-to-urban migration, which exacerbates existing water demand issues. Water scarcity and weaponization encourage migration, which increases pressure on the area where migrants have relocated to. The increased demand for water with no corresponding increase in supply, especially in developing countries already facing environmental challenges, results in a water shortage that further impacts refugees and migrants.

The growing population in urban areas imposes unsustainable burdens on water supply, and the loss of livelihood due to increasing water scarcity in communities already vulnerable to climate-related crises thus exacerbates migration. Migration is often recognized as an adaptive response to socio-environmental conditions; therefore, various implications of water availability push families to move from rural to urban areas. Furthermore, high population density and limited water resources directly impact migration patterns in conflict-affected areas.

Between 1970 and 2001, the population in the region increased from 173 million to 386 million. Overpopulation in rural communities increases competition for employment, driving the need to search for jobs elsewhere. Both cities and rural areas are dealing with this increased population density, but families continue to move from rural to urban areas in search of economic opportunities. Lack of water security contributes especially to the migration of lower-income individuals, as they are unable to sustain agricultural practices.

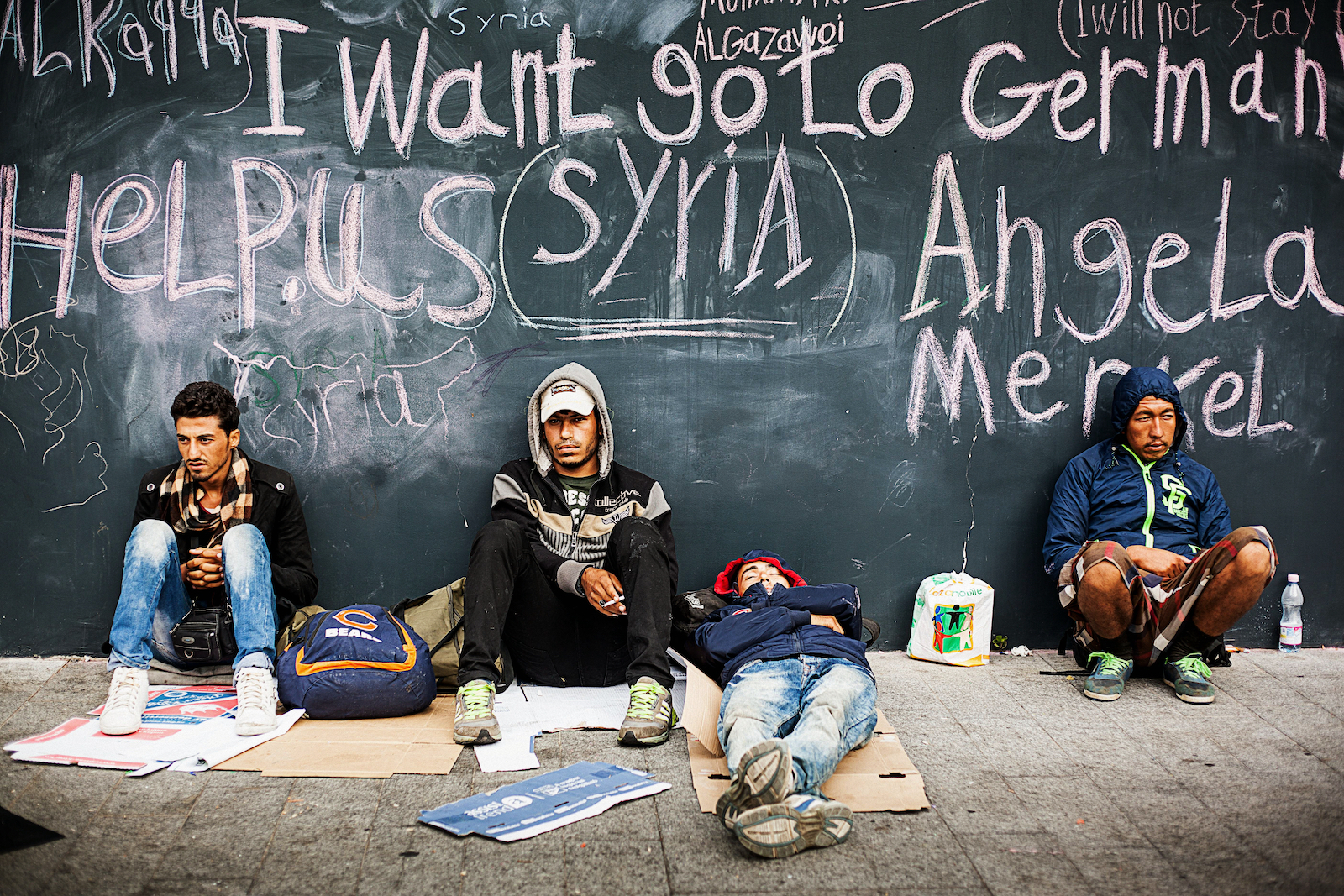

The Syrian conflict forced many families to abandon their rural farmlands in favor of urban areas, hoping for new opportunities; their hopeful migration, however, brings further sociopolitical stressors. The drought between 2006 and 2011 in Syria’s Levant region led to widespread failures of agricultural systems and social structures, internally displacing more than 6.7 million Syrians since 2011. While conflict and political disputes are a major driving force for Syrian refugees and displaced people within the country, poor governance places increased pressure on the country’s already failing water management system. The World Water Development Report of 2016 explains that there is a “clear connection between water scarcity, food insecurity, and social instability and potentially violent conflicts, which in turn can trigger and intensify migration patterns through the world.”

The lack of water negatively impacts crop cultivation and harvest practices, such that agricultural practices produce fewer food resources and higher prices in an already impoverished society. According to a UN Security Council report from October 2021, Syrians continue to struggle with access to sufficient and safe water, which has led to high rates of food insecurity and negative health implications. Food insecurity and poor healthcare are recognized as both drivers and consequences of migration. Lack of access to healthcare, clean water, and food during mobility creates poor living conditions within the migration process. Climate variability, food insecurity, and migration within the region are thus interconnected.

Migration exacerbated by water scarcity is one of the foremost issues on the global political agenda. Due to poor governance and water management, millions of families migrate to increase their chances of survival, especially as extremist groups exploit their vulnerability. Climate change disrupts weather activity, making the availability of water unpredictable, and extreme weather patterns prevent communities from accessing clean water. As the region continues to face the increasingly harmful impacts of climate change, its instability and inability to protect refugees, due to both environmental challenges and preexisting political and social issues, presents a significant threat to international security.

The breakdown of governmental authorities and the rise of armed groups throughout the region continues to displace millions of people and strain bordering nations. If current climate and conflict trends continue, the risk of wars being fought over water access will only increase. Humanitarian agencies and the international community must act now to ensure sustainable governance and protection for both refugees and host states.